![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Contents Under Pressure

When some former taggers picked a long-vandalized stretch of wall in Watsonville to spray-paint a mural that stretched over more than a tenth of a mile, it generated some buzz and also some controversy. But when the city was pressured into whitewashing it, that same wall became a blank slate for a debate over graffiti and public art.

By Sarah Phelan

Two months ago, graffiti writers Jason Anderson and Joe Corcoran were feeling on top of the world. After years of painting illegally under bridges and on alley walls--often at 4 in the morning. and always with the threat of arrest pumping adrenaline through their veins--the duo, along with 40 fellow artists, had decorated a one-tenth of a mile-long wall in Watsonville. And done it legally. Or so they thought.

Composed of 42 panels and located on the inside wall of a privately owned apple orchard, their masterpiece could only be seen by accessing the orchard. Still, it generated a fair amount of buzz in a city not traditionally known for edgy public art, and drew buckets of praise from members of the local art community and other admirers.

It also triggered what one city employee described as "horrible hysteria" among some neighbors--neighbors who apparently had the clout to get the city to suddenly discover that it was responsible for a wall that had been gratuitously vandalized for years, and then fork out $600 to whitewash every last panel of the mural.

Within two weeks of being finished, it was gone. It all happened so fast that Anderson and the other artists involved, including locals Justin Cox, Matthew James Powell and Shane Jessup, didn't even know their mural was going to be whitewashed until the deed had already been done.

"You should have seen the look on Jason's face. He was really disappointed, he put a lot of effort into that mural. It was really artistic," says orchard operator Israel Zepeda, who got a call from what he calls "some big shots in the city" after the mural went up.

"They asked if I knew who'd painted it, and I told them a bunch of guys had approached me and I'd told them it wasn't my wall, but that I didn't mind because they were gentlemanly enough to ask my permission."

Zepeda says the city then did some rapid research and determined that it partly owned the wall, at which point they sent someone to paint it.

"Which was too bad," he says " Young people have to do something. Some neighbors said there was loud music and drinking, but I was there and can say that though there were 12 people at one time, none of them were drinking, the music was not loud--and this was definitely better than the usual tagging on my wall. This was a mural done by a bunch of good guys who did a lot of good work--except maybe for the naked lady."

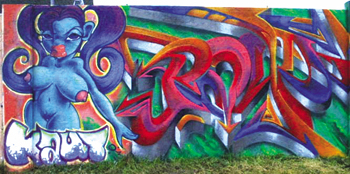

Turns out that one of the 42 panels featured a bluish green alien-looking woman with huge exposed breasts, twin details that apparently proved too much for the neighbors across the way.

As Watsonville City Councilmember Judy Doering Nielsen puts it, "While art is in the eye of the beholder, for me a panel featuring a large oversized women's breasts with a sign saying 'Tits' over them isn't appropriate anywhere--and especially not when in an area in which there are a lot of kids."

Anderson replies that the project was not on a major street, or highly invasive, and that panel was meant to be a self-portrait by the only female graffiti writer in the group."

As for "tits" being sprawled across said panel's breasts, that was apparently a misunderstanding (you can judge for yourself in the surviving photo).

"No way," Anderson says. "That was just writing somewhere else, someone else's name. But if they had a problem with that panel, they could have painted on a T-shirt or a bikini, not paint over an entire one-tenth of a mile-long wall."

Apparently, however, overexposed breasts were only the tip of the iceberg.

Nielsen says she received numerous calls from neighbors living in the subdivision across from the site of the wall at Cressview and Brewington streets, neighbors who were concerned to see lots of kids going through a broken fence to gain access to said mural.

"The landowner, who lives in San Jose, did not know anything about it," she says. "And though the person renting gave his permission, the kids were gaining access from the residential area, and the broken-down fence looked awful and there was lots of trash scattered everywhere."

Nielsen, who herself lives near the offending wall, says a mural normally has to be approved before it can be painted on city land.

"Artists have to submit renderings ahead of time, whereas this was a lease holding farmer who said, 'Sure, paint that fence,' and a bunch of kids with no permit, and no authorization. I literally passed on tons of emails and phone calls to our city manager. People were really upset. Why paint breasts and tits in a neighborhood? Anytime anything happens in my district, I should be informed. And the neighbors have a right to know and have input in what happens in their neighborhood."

At Nielsen's request, the city manager researched the wall and found that it was built at the same time as the subdivision at Cressview and Brewington, and so belongs to the city--thus giving the city the right to repaint it.

Asked if Anderson and his fellow artists could do a mural with a permit somewhere else in Watsonville, Nielsen said, "We usually work with people who live in the neighborhood, not groups that come from the outside."

Although some of the artists are local, others came from as far afield as Seattle, Vancouver and Montana (see sidebar).

Anderson and his fellow artists readily admit that their entrance into the world of graffiti writing was illegal, but they say that these days they are fully committed to practicing their craft aboveboard.

As such, they say they did everything they could to ensure they had stakeholder buy-in before so much as unsnapping a spray paint can, beginning with getting the blessing of orchard operator Israel Zepeda.

Zepeda readily signed their commission slip, because, as he puts it, "the wall was a constant target for taggers," and he hoped "this mural might help put an end to the cycle of vandalism."

Anderson also visited the Watsonville planning department, where a city planner told him no permits were needed, since the wall was on private property.

He even dropped a copy of the permission slip at the Watsonville Police Department, who put it on file in what they call their "Red Book."

"We figured the neighbors would call the police, which some of them did, so when the police showed up, we showed them a copy of the letter, at which point they became really supportive," recalls Anderson.

To make sure this wouldn't be a slip-slop jumbled mess job, Anderson and his fellow artists began the project by taking two days to paint over all existing gang graffiti.

"The wall was pretty wrecked before we started, so we spent our own time and money buffing it, then came back on the weekend to complete the project," says Anderson, who estimates that participants spent $100-$4,000 each on painting materials.

When the time came to paint, Anderson and company divided the wall into 42 panels, each 16 feet across and 8 feet high, and involved only people they'd known for years, artists who produce what they call "real tight quality work."

As a result, "when the neighbors finally saw what we were doing, most of them became really supportive. People from the Planning Department came, too. They sent everyone except the Coast Guard," Anderson recalls.

Fellow graffiti artist Justin Cox says a lot of residents who were out walking their dogs came by and said they loved it, too.

"They all seemed really stoked--except for one lady, who was taking pictures with her digital camera and gave me nothing but venom," he says, speculating that the mystery photographer was "the one with clout," because within two weeks, the city had painted over the panels--a move that left him feeling "totally and utterly bummed."

As for accusations of loud music, trash and broken fences, Cox says one person brought a portable radio and that while they piled up the trash over night, it was all removed by the project's end--and the chain link fence was already down and damaged.

"It wasn't like we were climbing through a hole," he says.

As for the notion that they aren't from the hood, Anderson and Cox bristle at the idea.

"I went to Monte Vista High School, I was born and raised here. We're about as local as it gets. And I used to do the biz cards for all the people working for Watsonville city government," says Anderson. Adds Cox, who grew up in Capitola, 'We're not graffiti vandals or tagger kids. This is how I make a living and pay my bills."

This is not the first time a city has whitewashed the group's art.

Last summer, after they painted a big skull, dagger and roses for Graffix Pleasure in Santa Cruz, a shooting happened in the store and the mural was painted over.

"It seems any time you spray paint something, people say its gang related, which is the furthest thing from our mind. We got paid to do that job, so it was pretty discouraging," Anderson says.

The Watsonville situation is possibly even more discouraging.

"I could even see the city of Watsonville's point of view, if it had been on the other side of the wall," he says, "but in a field where no one can see it? Seems like the $600 it took to paint over it could have been better allocated."

Suzi Aratin is the city planner who originally met with Anderson before the mural was painted and told him he did not need a permit. She calls the ensuing mess "one of these sad situations" and admits the wall had a long history of people vandalizing it.

"Up until now neither the city nor the county claimed jurisdiction, so the wall went 20 years without any legal backup. But because of neighbors freaking out, the city reviewed the property and found it's their responsibility to maintain the wall. So, the wall was painted over and from now on the city will be doing grafitti abatement," she says.

Asked what she thought of the mural, Aratin says, "it was really cool, except for the half-naked woman. If you're gonna be painting right across from a subdivision, don't put in inappropriate images."

Though the artists are trying to take a Zen approach to what happened, Anderson says the whitewash left him feeling violated.

"If we'd have done that with paint brushes, people would have awarded us medals, but because it was done with spray paint, it's seen as graffiti, something that must be done away with. All of us are really bummed, we had high hopes for future. It was one of the best collaborative projects any of us have ever done. It's really frustrating."

Still, the "cleanup" has not dampened his enthusiasm or determination to practice his art within the letter of the law.

"We're looking for another wall, not as big, but somewhere we can express ourselves, somewhere that will keep kids from working on illegal sites. I'm old enough, and I'm married with kids, that I don't want to have to paint under bridges," said Anderson, 29. "A few locals like Bill Ackerman, who owns the Skateboard Shop on Soquel Avenue, are very supportive. He let us paint walls around his store and when he did skateboard demos, he would build walls we could decorate and not get into it trouble and arrested," he says.

In the meantime, Prey for Art manager Amy Sorrells is providing an outlet for the legal display of the work of Anderson, Cox and seven other artists involved in the short-lived Watsonville mural.

"I'm very impressed they did this with spray cans, because it looked as if they did it with a ruler," says Sorrells. "When I heard what had happened, I thought this can only send a negative message, since it suggests what they did was a criminal activity. Yes, the roots of their art are criminal, but they've refined it, so that it's not so angry, and they've brought it more beauty."

Sorrells believes the group's good attitude and work could change the public's opinion of graffiti art, which has been soured because people understandably don't want their property tagged.

As Sorrells puts it, "All criminal activity stems from the lack of any greater outlets, and this group of artists is very special in that they can educate the community and be positive role models for future generations, who won't be interested in tagging if they see this art has audiences interested in purchasing it."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Caught in the Spray: Jason Anderson (left) and Justin Cox were two of the artists behind the mural.

The Breast Defense: This panel of the mural was the one critics say got it painted over. Apparently, some also misread the artist's signature as an anatomical reference.

Canned Art: A long view of the wall before the city painted over it.

Urban Scrawl: This was one of 42 panels in the Watsonville mural.

Paid in Full is Prey for Art's grand opening exhibition and features the Walls 2 Riches Collective of Jason Anderson, Justin Cox, Clown 2076, Dr. Kolage, Shane Jessup, Moby, Lucas Musgrave, Paydirt, Pear and Retro. April 26-May 31, 1115 Soquel Ave., Santa Cruz; 831.459.8891.

From the April 30-May 7, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.