![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Ecstatic Dance

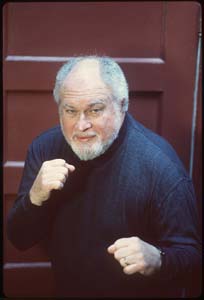

Jana Marcus

The poetic vision of Santa Cruz County Artist of the Year Morton Marcus

By Geoffrey Dunn

FOR MY 44th birthday earlier this month, the poet Morton Marcus gave me a copy of Fyodor Dostoevski's The Brothers Karamazov. Marcus inscribed the book "to my bro ...," a simple, yet significant, recognition of camaraderie and brotherhood--relationships that matter profoundly to Marcus, who, as an only child, was shipped from boarding school to boarding school, without any sense of family or place.

"That book, I think, should be like everyone's bible," Marcus explains in his rasp of a voice that still bears strong traces of his Brooklyn roots. "Because it tells them where they are in the 20th century, what the problems are in the 20th century reduced to the personal. It is done in such a way that it just hits your head and hits your heart and becomes an overwhelming experience."

One of the characters in Brothers is a visionary holy man named Father Zossima. Irascible and arrogant in his youth, Zossima experiences a powerful transformation in the novel, one in which he sheds the trappings of ego and self, until finally, in full humility and with unrelenting gratitude for the earthly bounty he had been graced with, he gets down on his knees and kisses the ground.

Marcus' life was irrevocably changed by that literary realization.

"I searched a long while to find a place where I could perform such an act," Marcus declares. "For me, Santa Cruz is that place. I have lived all the tragedies and all the joys of my life here."

Weep With Wings

IN THE LITTLE more than three decades since Marcus first arrived in Santa Cruz and declared the then rough-hewn seaside town his home, he has kissed the community as poet, teacher, father, husband, lover, friend, fighter, film historian, essayist, political activist and union organizer. He has become so intimately entwined with the cultural and social fabric of Santa Cruz County that it is hard to imagine it without him.

He has published seven books of poetry--for which he has received an international reputation--along with a popular novel. More than 400 of his poems have been included in literary journals around the world, and he has been collected in 75 poetry anthologies, including the seminal Young American Poets.

His work, driven by concrete imagery and internal word play, has been influenced, he says, by the likes of the Russian masters (Chekhov, Dostoevski, Isaac Babel); by Rabelais and "the idiot savants"; by Vasko Popa, Neruda and Cervantes; by Su Tung-po and Chuang Tzu; and by Phillip Levine and Eduardo Galeano among his contemporaries--and a host of others.

"I'm Jewish," Marcus notes, "but I'm Russian-Jewish, and I've always identified with the Russian part of me, and I'm not American. This is really a WASP country, and so many people misunderstand me--misunderstand my intensity, misunderstand my emotionality. I am really Slavic in temperament, and I try to devour the world and the world could destroy me and I could weep with its wings and I could laugh with its wings and that was how I was going to face the world in my poetry."

Writer and filmmaker Andrei Codrescu has written that Marcus "is the kind of priest-poet who, like Peguy or Jacob, gets to the Light by tearing up the universe in ecstatic dance." Novelist Al Young has called him "one of America's hidden literary treasures," while Pulitzer Prize-winner Charles Simic labeled him "one of the most readable and moving poets of our generation."

His daughter, photographer Jana Marcus (who took the pictures for this article), calls him simply "a sage."

With an actor's sense of the dramatic inspired by the young Brando, Marcus is a spellbinding reader, and he has been invited to give readings throughout the U.S., Europe and Australia.

In addition to his poetic output, Marcus taught English and film for 30 years at Cabrillo College, during which time he influenced a generation of Santa Cruz poets and film aficionados. He is currently serving as a television host for KRUZ's Cinema Scene (TCI Channel 3), while Movie Milestones, a 16-part documentary series that he wrote and co-produced with Stuart Roe, appears weekly on Community Television of Santa Cruz County (Channel 72).

Twice each month on Saturday mornings, he conducts film discussions at the Nickleodeon Theater, and he was recently honored by Santa Cruz Friends of the Library, which produced a poster featuring one of his poems and the artwork of James Aschbacher. He hosts a poetry show on KUSP-FM radio, and is coordinating this year's Pacific Rim Film Festival.

You can even see one of his poems on local buses as part of county Parks and Recreation's "Mobile Muse" program. The guy's poetry literally gets around.

For all of these artistic contributions to the community and more, Marcus has been named Artist of the Year by the Santa Cruz County Arts Commission. On April 30, at the Museum of Art & History, Marcus will present a retrospective reading of his work in recognition of this honor.

"This is really an important award," Marcus acknowledges. "First off, it puts me in company with three other writers who have been so honored: Adrienne Rich, Jim Houston and William Everson. Second, I think it's important to be recognized by my own community."

Marcus is passionate about the active role that he feels the poet--and poetry--should play in contemporary society. "I want the poet to have a role in community whereby he or she really influences the way things are perceived and therefore the way politics and business take place. ... Poetry should change your life. It should change your spirit. I really liken the poet to the shamans and holy men and prophets in other cultures that have been taken that seriously."

Pictures in Words

TO UNDERSTAND the poetic vision of Morton Marcus, one must understand his brittle, fragmented and often painful Catcher in the Rye-meets-Studs Lonigan childhood.

Born in 1936 to Russian-Jewish immigrants in Depression-era Brooklyn, Marcus, by the time he was 3, was shipped off to boarding school, only to be returned home, then shipped off again--a pattern that would be repeated more than a dozen times throughout his youth. He met his father briefly on only two occasions, both times at legal proceedings involving his mother.

"Not only was I constantly the new kid at these damn schools," Marcus recalls emphatically, "I was always the new Jewish kid. I either had to get tough and learn to fight or get the shit kicked out of me all the time. So I learned to fight. I got tough."

He also developed a profound sense of compassion: "A lot of the kids who were in my situation continued to get beaten up for their whole fuckin' youth. When I became a fighter and became, really, a guy who went for the throat, I became a defender of all the kids who were always getting bullied."

The acute sense of anomie he felt, the rootlessness, the isolation, also led him to flights of imagination. "I began to talk to myself, and then tell myself stories, and the language of those stories became absolutely fascinating to me. ... I began to draw pictures in words, and that is the source of my poetry."

"I could understand where people were coming from," Marcus continues, "and it seemed to me that is the 'poetic vision'--the vision of being in the situation and yet being able to remove yourself from a situation and understanding what was going on or hopefully thinking I could understand what was going on."

For Marcus, it is a dichotomous vision with dual sides that ultimately fold in on one another. "I mean, when I see two young lovers walking on the beach hand in hand, you know, in the bloom of their first moment of romance, I feel happiness for them, and joy, and I feel tremendous sadness and I start to get teary-eyed. Because I see those hands holding each other, which are not going to be holding each other. And even if they hold each other for 30 or 40 years, they're going to be older hands and that whole thing is going to change in the whole course of life, and I just see this whole huge vision--these endless cycles we seem to be caught in, that Blake talks about. It is my poetic vision. It is a tragic vision which somehow, in my case, suddenly gets infused with absolute comedy."

Marcus says he sees himself and his poetry in the tradition of "the idiot savants and the holy goofs--these people who are clowns and who say profound insightful things about our spiritual life and our physical life and our intellectual life. ... I think it's a very Jewish thing. I really do."

Cosmic Constellation

DURING HIS EARLY TEENS, Marcus was already something of a streetwise hustler, and he took up boxing (a sport that he still follows with great passion) and basketball, in which he found poetic inspiration.

"John Wooden [the former UCLA basketball coach] has called basketball a 'cosmic constellation,' " he says. "That's how I understood the game even as a kid." Marcus was good enough in the back court to land an athletic scholarship to an upscale prep school. He failed out at the age of 17 with poor grades.

Following a "wild" four-year stint in the Air Force, during which he published his first poetry, Marcus enrolled in 1958 at the University of Iowa, home of the famed Writers Workshops. After winning a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship in 1961, Marcus came west to study in the masters program in creative writing at Stanford, headed by the legendary Wallace Stegner. It was there that he met a cadre of talented and energetic young writers, including the young novelist Jim Houston, who would later encourage Marcus to move to Santa Cruz in 1968.

In the interim, Marcus, who was married (to his first wife, Wilma, still a celebrated theater arts instructor at Cabrillo) and the father of two children (Jana and Valerie--the latter studies costume design at New York University), took a job teaching high school and coaching basketball in San Francisco. He immediately became active in the political and cultural life of the city, organizing poetry readings and serving as chair of the Artists Liberation Front, which actively opposed the war in Vietnam.

By the time Marcus and his young family moved south to Santa Cruz in 1968, the city was in a period of profound transition. The arrival of the University of California and the emergence of a new counterculture had turned Santa Cruz into a creative mecca.

Marcus settled in and kissed the earth. He founded the Cabrillo Poetry Series, which brought to the local community college some of the most important poets of the era: Allen Ginsburg, Robert Bly, Adrienne Rich, Phillip Levine, Diane DiPrima, Gary Soto, Vasko Popa. He organized readings at local restaurants. And he continued to publish widely: in The Nation, The Chicago Review, Kayak, The Colorado State Review.

In 1969, his first book of poetry, Origins, was published by George Hitchcock in San Francisco. In an inspired six-month spurt, Marcus had written more than 160 poems focusing on such primal issues as family and death, and Hitchcock was determined to print the best of them.

Constructed in a spare, close-cropped style, this poetry was clearly inspired by the writings of the Czech poet Popa, to whom he dedicated the collection. "There is a strong Slavic connection in these poems, a connection with which I have always strongly identified," Marcus noted.

The success of Origins solidified Marcus' reputation as a poet, launched a nationwide reading tour and landed him in the Young American Poets Anthology. It was a heady time. Three years later, Noel Young of Capra Press published a pair of collections, Where the Oceans Cover Us and The Santa Cruz Mountain Poems.

Where the Oceans Cover Us actually included some of Marcus' earliest writings dating back to the 1950s, as well as several poems from an unpublished collection, Toward Certain Divorce, which chronicled the recent breakup of his marriage. In "Watching Your Gray Eyes" he wrote:

"I remember when I had this huge tour in 1970 across the United States," Marcus recalls. "What happened on that tour was that I was writing nature poems. Those are the poems that I read, and I mean, editors, poets who loved my earlier work, they just said, 'Geez, um and ah,' after the readings. I mean, they couldn't even look at me. You know, like, 'That's not why we like your poetry; we like the jocular, ironic, satirical poet of Origins, you see,' and I said, 'Well, this is not what I'm doing now.' "

Each Dawn a Bird

THE CREATIVE OUTPUT slowed down for much of the next decade as Marcus focused on his teaching duties at Cabrillo. "I had so many papers to correct," he says. "Cabrillo had taken me over. I was experimenting with new courses. It was so much preparation. It was so much giving myself to others."

In 1977, a small, local publisher, Jazz Press, came out with a volume of prose poems, Armies Encamped in the Fields, which was illustrated by Santa Cruz artist Futzie Nutzle. Jazz Press also published, in 1980, Big Winds, Glass Mornings, Shadows Cast by Stars, a collection of his work over the past eight years. It included a moving elegy dedicated to his two daughters:

"What I was really looking for all those years was someone who I could share a rapport with and who I could share being with. She's my best friend, as well as my lover-wife, but she is also a person of enormous honesty and integrity. It is because she is an independent human being who has gotten a career of her own and has forged on through travails in her own life that has made her the person who's so important to me--whom I respect and love so much."

Perhaps in response to this revived sense of family, Marcus embarked on a series of poems that became Portraits From a Scrapbook of Immigrants, a powerful collection that returns to the seminal themes of Origins, but in a more personal and character-driven fashion. The book, which went through several rewrites over a grueling seven-year period, marked a personal triumph for Marcus and includes some of his most accomplished poetry.

His creative juices flowing once again, Marcus became obsessed with the history of film. In 1987, he began work on a 1,000-page manuscript, Movie Milestones, that served as the script outline for his documentary series but which Marcus has yet to complete. "Call it a work in progress," he says.

With a pattern of circling back on his career, in the early 1990s Marcus began experimenting once again with prose poems--as he had during the era leading up to Armies Encamped. The result was When People Could Fly, an archetypal exploration into Marcus' imagination that serves as modern-day myth and folk tale.

"When I came back to the prose poem, I knew one thing that I was doing: I was getting away from the tyranny of the line. It allowed it to be opened up to these wacko changes of thought that come with me all the time. That is what happens in the prose poem. Suddenly I'm over here, and I'm way over here and then I come back and I join both of them together or I go off in a totally different angle. It is so delightful to be able to engage that and yet keep my discipline so strict. I must say I have never felt the freedom, or the power, that I do now in the prose poem."

The results of these recent endeavors have been so successful that literary critic Alan Cheuse has dubbed Marcus "the godfather" of the prose poem.

Dancing Bear

AS MARCUS CELEBRATES his 62nd year, he remains creatively vital and decidedly productive. A dancing-bear of a man, with broad shoulders and a purposeful stride, he is nonetheless capable of delightful frivolity and outbursts of joy. And then he can turn deadly serious.

As we sit in his cluttered second-story study one afternoon in early spring, I ask him what it is that kept him going.

"I think artists are obsessed with leaving something after they're dead," he declares somberly. "I really do. What keeps me going, you know, and it's really a love-hate thing, I mean, I got to say, I am really obsessed with death, and though I see the whole continuum of life and all that, I just--I really hate to say--it's bad news at the end. But I do love life. And so I put my head down and do the work."

Whether he will continue to create in the prose-poem form for the rest of his career, he isn't sure.

"I consciously pursue a different style or a different approach to my work," he says. "I think it keeps you from getting too comfortable, from not pushing yourself. So I don't get locked in. I've described this as like a painter going through a phase--you know, Picasso in his Blue Phase--and that's to keep it regenerated and ever new and hopefully even keep my subject matter new and different, though I can see the same themes coming up over and over again."

I remind him of Robert Frost's observation that most American writers never write anything of importance after the age of 40.

"When do you run out of this vitality? When do you run out of the imagination? I hope that never happens. I hope I come to life fresh and new, because what it's about for a writer, what it's about for an artist is not the afterlife, it is this life. It is the world around us--socially, politically, spiritually--it is while we're here. It is the skunk cabbage of human experience--and that's all that concerns me."

Writer and filmmaker Geoffrey Dunn is the author of Santa Cruz Is in the Heart and director of the documentaries Miss? or Myth? and Dollar a Day, Ten Cents a Dance. He is currently a lecturer at UCSC and executive director of Community Television of Santa Cruz.

Photographer Jana Marcus is the author of In the Shadow of the Vampire: Reflections From the World of Anne Rice.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Mobile Muse: Morton Marcus is passionate about the active role that he feels the poet--and poetry--should play in society.

Mobile Muse: Morton Marcus is passionate about the active role that he feels the poet--and poetry--should play in society.

I want to live at that pitch which is near madness, but disciplined by art.

--Morton Marcus

Poetry in the Air: A yearbook photo from 1967 shows high school teacher Marcus injecting some high-energy verse into the classroom.

I remember all those girls

The Santa Cruz Mountain Poems (recently republished by the Capitola Book Company) marked yet another shift in Marcus' style and once again reflected an immediate influence--this time Taoism and the poetic traditions of China and Japan. While Marcus' poetry up to this point was saturated with the dramas and tribulations of human life, The Santa Cruz Mountain Poems centered on the spiritual world of nature:

opening themselves like books

and the back seats of Chevrolets,

and realize that what you have of me

I received from them, outside bars

called Bloody Bucket, Preacher's, Hanging Loose:

faces eaten away by fog and rain,

names I sometimes never knew

Dawn. The stones

The sudden fluctuations in style and content, however, left some reviewers perplexed. The poet who had crafted the Slavic-influenced Origins had seemingly no relationship to the Taoist Santa Cruz Mountain Poems. The reaction also did nothing to enhance his literary reputation.

lean toward the sun.

They rise from their haunches.

From everywhere in the meadow

they drag themselves

out of their weights,

lifting in unison

like an exhaled breath.

Remember

By 1980, Marcus was switching literary gears again, this time spinning a popular spy thriller titled The Brezhnev Memo. The new decade also marked the beginning of a new relationship for Marcus--with Santa Cruz native Donna Mekis, now an administrator at Cabrillo College, and her young son, Nicholas Galli. Mekis' family roots stretch back to the Yugoslavian community in Watsonville and to the Konavle Valley in southern Croatia. It was a powerful bond for Marcus, providing him with a sense of stability--and rootedness--that had eluded him since his divorce.

that today is forever,

each dawn a bird,

and that this bird,

whether pink or gray,

has flown around the back of your lives

and returns each day

to be filled with everything you are

and want to be

and will become.

Morton Marcus will present a retrospective reading of his work April 30 at 7:30pm at the Museum of Art & History, 705 Front St., Santa Cruz.

From the April 21-28, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.