![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

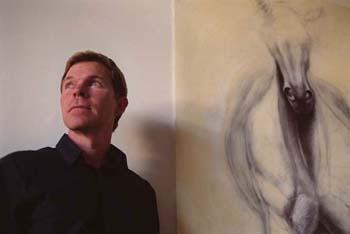

Fine Lines Online: Artist Tobin Keller's virtual gallery has netted online art sales--and burdened him with additional marketing chores that compete for creative time.

Web Van Gogh

Artists taking their studios and galleries online struggle with the technology of the Internet and the commodification of their work

By Bruce Willey

INSIDE HER NEWLY apportioned laundry room, Kate Noland stares raptly into her computer screen, jiggling a mouse. Library books about designing websites lie open on chairs that for now serve as shelves. On the screen is a rough-up of her website, but she just can't seem to get the text and the pictures to line up the way she wants.

A self-professed Luddite, Noland has made one concession to the prevailing age: her first computer, a hand-me-down from her father. Judging by the frustration the computer causes her, I get the feeling she could live a perfectly happy life without all this progress. But she is determined to create a website and sell her wares over the Internet.

Noland has had shows in San Francisco, San Jose and Santa Cruz, she says, "but the galleries always took 50 percent--if they sold one piece--which was just about the cost to frame them. I figured I was making two cents an hour for my efforts. Not very inspiring."

There has always been a disparate and sometimes testy relationship between artists and the public that buys their art. Yet the romantic notion that business is the antithesis of art doesn't work for the artist who wants to survive. With an eye on the Internet and its worldwide audience, Noland hopes to sell more of her work and take the commission as well. But first she has to figure out how to create a website.

IF E-COMMERCE companies sell books, CDs, antiques, gas and even groceries, it was only a matter of time before someone started hawking art over the Internet, too. However, what makes this type of transaction particularly complex is that art loses its inherent aesthetic value when it is overly commodified, even if its material value goes up. That's the bad side.

The good side is the Internet may also foster a new form of art appreciation, one that benefits artist and collectors alike. By bypassing the traditional means of selling and displaying their works, artists might reach a larger audience and not be subject to the whims of the bricks, mortar and track-light gallery economy.

But could Theo have sold Vincent's Sunflowers if an ISP in Provence had started up a hundred years sooner, thus saving the artist from giving his ear to a prostitute in sheer artistic desperation? Or, skipping to the present with the same wish list, can the Internet save an artist from a life of poverty? These are some of the questions I had when I visited Tobin Keller's website the old-fashioned way. I drove.

Just below the hills that separate Gilroy from Watsonville, Keller's sizable horse ranch is landscaped with jumps and other horse apparati. He invites me into his stainless-steel studio with big windows facing east to catch the morning light.

"One of the reasons I started my website was to maintain my independence," Keller explains. When he was designing the site, he drew out the plans and ideas on paper and hired a web designer and marketer to build it.

"I did the grunt work myself because I had a certain look in mind, and it saved me a lot of money," he says, leaning an elbow on one of his sketches. "Selling work is difficult no matter how you sell it. I spend at least 50 percent of the time on marketing my work. And the web has only increased that marketing work, which ultimately means I have less time for art and no time for laundry."

Keller makes it clear that a website is not an easy sell. He has purchased banners; listed with 23 different search engines; given away books to drive traffic; designed, printed and distributed postcards to galleries with his website listed on them; and marketed and promoted right through the tin roof of his studio. His efforts have succeeded. The computer in his office, along with the peripheral printer and fancy scanner, are paid for thanks to a patron in Chicago who found and bought his art after doing an online search for botanical art.

"People will always need to see art in person to get its full effect," Keller says. "Galleries and museums are instrumental in this. The Internet won't change that."

I had found Keller's site through a link at Santa Cruz Visual Arts, a website run by Rick Jacoby--my next stop, just above Mission Street. Way back in 1992, which is the Pleistocene Epoch in web years, Jacoby put up a site list of local artists, galleries and art happenings. It was and continues to be a labor of love.

Even though he has worked 25 years for NASA Ames, Jacoby is the guy you'd choose from a lineup if the crime was being an artist from Santa Cruz. Behind his house, he shows me his studio and shop (http://www.cruzio.com/~scva/rickj.html), where he mostly creates sculptures out of wood and found objects that have a Polynesian look to them.

"When I first saw a radio station list its DJs on the web about 10 years ago, the idea hit me that you could do that with a community of artists--an interactive Pink Section, if you will," Jacoby says. "But artists were not exactly eager to sign up, and it was hard to convince people that the web was a viable way to promote your work."

Largely self-taught, both as an artist and a web designer, Jacoby generally charges a cheap hundred dollars to make a website for an artist. The artist then gets listed on Santa Cruz Visual Arts, which also has links to local galleries and artists who have made their own websites. "I tried to get some arts-related business to advertise, but like a lot of artists, I'm a terrible salesman."

INDEED, ART HERE has always been a tough sell. Santa Cruz doesn't have the reputation or the gallery space of other arts communities like Carmel. "That's old money down there. Old money with retiring time on their hands," Jacoby says.

However, the Cultural Council of Santa Cruz County is trying to change the perception that Santa Cruz is a hard art sell. Lynn Magruder, executive director of the council, sounds optimistic. "In the future, I think we'll see more collaboration between arts organizations and high-tech in the area of marketing. According to the Santa Cruz Technology Alliance, our community has 450 technology companies. The arts could really use their help."

Will Santa Cruz, which has at the very least a strong identity, be able to recognize its own image in the face of high-tech and the new money it brings in? High-tech is characterized not only by its frenetic, workaholic pace, but also by the very technologies themselves, which are outdated and obsolete a few months after they are made. This rapid cycle of change runs counter to art's timeless and endearing qualities regardless of definition and taste--from Turner to tattoos.

In a city that previously couldn't support fine art that the Pope Gallery offered, the question on many artists' minds is will the new money create a better market for art or will it drive artists out?

One person who doesn't seem to be worried about these changes is Dohna Lee, owner of Made in Santa Cruz, at the end of the Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf. The very name of her gallery says it all: proud, confident, as if all Santa Cruz artists are part of some impervious union.

C U See Art: Dohna Lee of Made in Santa Cruz plans to expand the store's art-on-the-web gallery offerings with a live webcam.

Lee is planning very soon to be able to offer customers online virtual tours of her gallery via a digital movie camera. "Some of the three-dimensional works here don't translate well on the Internet. This way I can walk them around our gallery," she says. "We've had great success with our website, and it has helped that we started early with an online presence."

One gallery that has taken the technology further is NextMonet.com. The company's not exactly in Santa Cruz, but if e-commerce really develops into the $184 billion industry Forrester Research predicts by 2004, it won't matter where NextMonet.com is located. For now, it helps that the company is based in San Francisco and that it is backed by CMGI@Venture, a venture-capital subsidiary of dotcom conglomerate CMGI.

NextMonet.com plans to bring the art of established and emerging contemporary artist to first-time buyers, not just art insiders. By this the company means buyers who are intimidated by art galleries and have no prior knowledge of art.

I quickly become overwhelmed by the enormous number of the little images (NextMonet.com has 5,000 works) and the waiting involved for them to load in my browser. Though I like a lot of the art, I feel a need for more personal interaction. I hit the personal online art-consultant button and come to a place where I can get online help about art. I answer the questions about myself truthfully, most of the time.

"I like abstract paintings and black-and-white photography," I write, "and I have a green couch, orange curtains and a red floor. What will both complement my decor and my exquisite tastes?" My personal art consultant, Kelly Dougherty, graciously sends six well-thought suggestions the next day. When I look them up, I figure that all the pieces will work with everything in my profile--except for the orange curtains.

ARTISTS HAVE GRAPPLED with balancing pureness against commerce for ages. Now they must grapple with the newest form of commodification. Will works that resist the soothing praises of the Internet, with its limited ability to convey real-world impact, sell or languish? And what of works that have a famous name attached to the bottom corner? Will those that have already been seen and sold in traditional galleries have an advantage online? There are no railings or guardrails along the art aisles of e-commerce yet--and this could work to the advantage of artists in tune with the web's maverick spirit.

When I go back to Kate Noland's studio to see how her website is coming along, she still doesn't have it up yet. But she has sold one her collages on eBay. Even so, she remains skeptical about selling art over the Internet.

Noland shows me her latest work: a beautiful, melancholy Italian man doll made from polymer clay. "Perhaps if I diversify and make a combination of arts and crafts I'll have more luck." The water in her tea kettle starts hissing, and she corrects herself. "You cannot pay an unknown artist to keep a pea on their plate. That's just the timeless plight of artists everywhere."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by David Heller

Photograph by David Heller

From the April 19-26, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.