![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Milk It

Author Melanie DuPuis asks if milk is nature's perfect food or one of its deadly poisons

By Rebecca Patt

EVERYWHERE WE TURN, we see movie stars, politicians and athletes asking the same ol' question: Got Milk? I've heard there's no use crying over spilled milk, and 'Milk: it does a body good.' But just how did this drink become an institution and this country the land of milk and honey?

In the classic American way, Mom raised me on (mostly chocolate) milk, delivered weekly in glass bottles to our suburban home. I remember delighting as chocolate milk spurted from Jeremy Kirtz's nostrils when I told my best knock-knock joke. Twenty years later, every school lunch still includes that kid-sized portion of milk in that impossible-to-open carton.

Yet I've never had a clue as to why cow's milk--obviously intended for calves, not kids--is such a staple in the American diet, until I read UCSC sociology professor Melanie DuPuis's new book, Nature's Perfect Food: How Milk Became America's Drink. DuPuis reveals how Americans came to embrace milk as a wholesome, body-building beverage, and how the United States came to be the largest milk-producing country on the planet, producing 153 billion pounds a year.

Despite a plethora of ads featuring ethnically diverse celebrities sporting milk mustaches, DuPuis points out that only Saharan nomads and Northern Europeans are genetically adapted to lactose tolerance.

Milk first came into prominence in American kitchens in the 1850s, DuPuis explains. Before then, most milk peddled on the city streets was buttermilk (a byproduct of the butter-making industry), most of which ended up as hog slop. But during the Victorian era, a breakdown occurred in the traditional female social structures that promoted breast-feeding, says DuPuis. Women began increasingly replacing mother's with cow's milk, as urbanization found more working-class women working in factories and upper-class women isolated in bourgeois worlds where breast-feeding had no place.

Women of that period were often presented, and presented themselves, as "excitable," writes DuPuis, and the then-current fashions in female temperament created concern that nervous emotions would affect breast-feeding babies.

"There is also some evidence that upper- and middle-class men strongly influenced their wives not to breast-feed, because of cultural mores proscribing sex during the period of nursing, and because of a desire to maintain their wives' fertility," says DuPuis.

Wet nurses were expensive, so the milk available to city women came from poorly nourished cows fed on leftover grain used in fermentation in city distilleries. Poor sanitation in the overcrowded and dirty dairies and lack of refrigeration often resulted in poisonous milk, a leading cause of the city's high infant mortality rate.

But instead of advocating a return to breast-feeding, that tried and true source of safe infant nutrition, temperance reformers rallied for milk reform and championed cow's milk as they fought to shut down the New York City distilleries. While milk today typically has a reputation for being tainted with antibiotic residues and hormones, the teetotalers celebrated milk as God's chosen beverage, a way to return to pastoral and holy perfection.

"The early temperance reformers were obsessed with the idea of creating the perfect society," says DuPuis. "They went to the Bible to figure out what God's design for the world is."

They interpreted that because God preferred Abel, a herder, over Cain, a farmer, he preferred milk.

By the end of the 19th century, in a continuing media blitz, multinational corporations began a milk advertising campaign that touted their product as a way to raise "prize-winning" babies.

DuPuis argues that milk is neither as good as the early temperance reformers and the modern Dairy Council claim nor as poisonous as today's vegan activists would have one believe.

"Both stories impose on our food what is really a situation between people," she says.

In her research, DuPuis found that social activists--from temperance reformers to today's critics of genetically modified food--have used milk as an organizing tool for the last 150 years.

DuPuis says her study of milk was akin to "a black hole that sucks you in and never lets you escape," because the topic is so complicated and fascinating.

She first became interested in milk while working for the New York State Assembly's Agricultural Committee. Her work there led her to question why dairy regulations are what she calls the "most arcane and confusing sets of laws you can imagine."

"There are probably five people in the U.S. who really understand dairy regulations," says Dupuis.

She explains the inundation of milk propaganda as part of a longstanding relationship between agriculture and politics. Dairy farmers, says DuPuis, are paid more money for fluid milk, so legislators support legislation that increases milk drinking and the advertising dollars pumped into promoting it.

And though the demand for fresh milk has decreased, dairy farmers stay in business providing milk for the burgeoning demand for pizza cheese.

"Under the circumstances we live in, drinking milk is good for you," she says. "Should we be drinking as much as the Dairy Council wants you to drink? Probably not, because their interest is not in health, it's in making the dairy farmers more money."

Many interested in health are now choosing alternative beverages for easier digestion and also because of concerns about biotechnology, pollutants and animal welfare. Dupuis says one-third of her UCSC students are vegans. Still, the power of an institution is great in the minds of consumers. Choosing rice or soy milk may be an alternative, but it certainly doesn't carry the same nostalgia. Can you imagine 6-year-old Jeremy, in a punctuation of unexpected laughter, streaming soy milk out his nose? It's not as funny.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

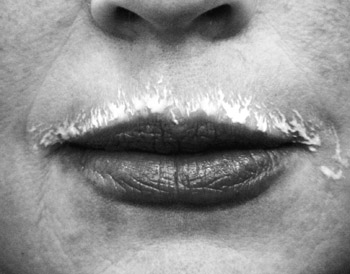

Udder Nonsense: Cow's milk is made for calves, argues author Melanie DuPuis.

Melanie DuPuis will discuss her book, 'Nature's Perfect Food: How Milk Became America's Drink,' at Bookshop Santa Cruz on Wednesday, April 17, at 7:30pm.

From the April 17-24, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.