Monterey's Time

Well-bred Red: Two glasses of Smith and Hook 1995 Cabernet Sauvignon frame the extensive vineyards at the Monterey County winery.

The next big revolution in California winemaking is happening next door in Monterey County

By Christopher Weir

EVERY MAJOR WINE REGION enjoys a moment when quality fulfills potential, when perceptions confirm predictions, when the future overwhelms the past. For Monterey County, that moment is now.

"The artisans have come to Monterey," says Rich Smith, owner of Paraiso Springs Vineyards in Soledad. "And the growers are increasingly motivated to be artisan-style growers."

For decades, Monterey County grapes have contributed to wines produced across California. More recently, several prominent wineries have stepped up their commitment to the county through vineyard purchases and winery projects. Mondavi, Kendall-Jackson and Gallo plan to build local production facilities, while Estancia recently established a winery outside Soledad. Caymus, Hess, Raymond, Bonny Doon Vineyards and Joseph Phelps also maintain strong vineyard ties to the county.

These developments imply a momentum that promises not only a new era for Monterey County wines but also a seismic shift in the Salinas Valley's rural identity and economic potential.

"I think you're going to see an incredible change in this area that is going to be all for the better," says Joel Burnstein, executive vice president and winemaker at San Saba Vineyard on Sims Road in Monterey. "When you have a number of wineries, you're talking about a big boost in those local economies."

Unlike the Santa Cruz Mountains, where the geography favors only limited agricultural conversion, Monterey County is loaded with ideal terrain for vineyards and, by default, wineries. According to Randall Grahm, owner of Santa Cruz-based Bonny Doon Vineyards, both the Santa Cruz Mountains and Monterey County are "fantastic" wine-growing regions with extended ripening seasons that ultimately enhance wine texture and flavor profiles.

But one major difference between the regions, Grahm notes, is volume potential. "There's no such thing as a large vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains," Grahm states. "You don't have the same kind of contiguous acreage that you have in Monterey County."

A burgeoning winemaking industry does not come without a price, however. Heightened winery development can create problems that are fundamentally alien to other agricultural enterprises. In other wine regions, the impulse to entertain the wine crowd has short-circuited the agricultural identity to which the attractions were originally wired.

"We've realized that it's more than just the wine in the bottle that you're selling," says Mary Handel, Napa County planning commissioner and former executive director of that county's grape-growers' association. "You're selling the ambiance and all the other things that go along with it. It's wonderful to have wineries and have an agricultural product that can bring in money to the area. But through it all, there's got to be a long-term vision that preserves and conserves the integrity of the agricultural land."

FOR TOO LONG, the Salinas Valley was perceived by outsiders as a monolithic winescape, the drone of its predictable climate defined by morning fog and high-velocity afternoon winds. Today, however, the valley is recognized as a mosaic of microclimates suitable to a wide range of grape varietals.

Monterey County is emerging as perhaps the premier region for chardonnay production in the U.S., a status prophesied by the track records of such local wineries as Morgan, Talbott and Chalone.

Pinot noir is also turning heads in cooler areas of the Salinas Valley. Meanwhile, sun-seeking red grapes such as cabernet sauvignon and merlot are yielding beautiful wines from the Carmel Valley and, more recently, from the southern reaches and warm pockets of the Salinas Valley. Pinot blanc, sauvignon blanc and riesling continue to perform well in various areas, while sangiovese, syrah and others are showing considerable promise.

"We have an incredible range of growing conditions," says Bill Anderson, winemaker at Chateau Julien.

As local winegrowers maximize the affinities between particular microclimates and varietals, several appellations--viticultural areas that denote specific growing conditions--have emerged with their own unique personalities. The Carmel Valley, Santa Lucia Highlands, Arroyo Seco, Chalone, Hames Valley, San Lucas and Monterey--these are the appellational names through which Monterey County's diverse and complex wine identity is increasingly refracted.

Monterey County's wine renaissance has not gone unnoticed. The industry's two leading consumer magazines--Wine Spectator and Wine Enthusiast--both recently published sprawling features on Monterey County. Already Monterey County boasts the largest contiguous vineyard in the U.S., the 7,500-acre San Bernabe property. Scheid Vineyards recently became the first vineyard to go public, selling two million shares on 4,950 acres for a total of $20 million.

"You're starting to see a real commitment of dollars by some very serious people in the wine industry," Burnstein says. "And it's only because of one reason: We have proven that the quality of our grapes will hold up to anyone's."

Still, the production deficit remains stark, with only about 25 percent of the county's fruit processed at local facilities. While Monterey County's vineyard acreage now exceeds that of Napa County, its 20 winery facilities are a mere fraction of Napa's winery base.

"Where are these grapes going?" Burnstein says. "I can tell you. Look for the milk trucks, look for the trucks with the big bins on them. They are all going north. It would be ridiculous to say, 'We want an agricultural community, we want all this space and the beauty that this farmland produces,' yet not allow the opportunity for the people who own the produce to process it nearby. All this fruit is moving to other places that are basically reaping the economic benefits of Monterey."

ALONG WITH heightened outside investment in Monterey County has been the steady rise of what Paraiso Springs Vineyards owner Rich Smith calls "artisan" vintners and growers. These are the local interests committed to producing handcrafted wines from high-quality grapes.

"This has been a kind of behind-the-scenes winemaking and viticultural area," says Steve Pessagno, winemaker at south county's Lockwood Vineyard. "But that's going to change. I think it's going to become much more prominent."

Adds Larry Bettiga, Monterey County's University of California viticulture farm advisor, "If you look over the past five to 10 years, that's been the major change in Monterey County. It's now a winery-driven acreage and production [situation] versus years ago, when it was mainly [independent] growers. Almost all of the fruit went out of the county to be processed. Now most of the acreage is owned or controlled by wineries, which is more of a stabilizing presence within this industry."

The increased prominence and stability of local wine production promise to yield significant changes for county wineries and inland tourism. "I would suspect that in the next five to eight years, you'll probably see a doubling in the number of tasting rooms, which still isn't a lot," Pessagno says. "But then it will probably take off. More and more, people are going to be finding Monterey County wines all over the country and world, and they will respond to that."

Burnstein agrees, saying, "Once we achieve what I call critical mass, all of a sudden people are going to take notice. I think you're going to start seeing wine tasting as a primary attraction, rather than 'Oh, that's available, too?' "

But while locally produced wines will soon challenge the North Coast on the consumer front, it will take years for Monterey County to even remotely rival Napa or Sonoma counties on the wine tourism front. For starters, there's the fact that Steinbeck Country is not the prototypical wine country.

"We have to do a little bit more romancing ourselves and promote the county as the wonderful place it is," Anderson says. "It's a different place than Napa. It's not full of redwoods and little creeks. The Salinas Valley is just so totally different, visually, from Napa. It may be a little bit of a visual shock to some people. But you talk about romance, this is it."

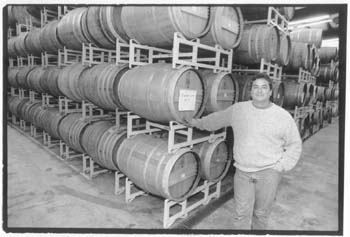

Roll Out the Barrels: Winemaker Larry Gomez shows off the French oak barrels he uses to age his best vintages at Lockwood Winery, south of King City.

THE SALINAS VALLEY is also unlike the North Coast on a number of other fronts. It is much vaster than Napa, Sonoma, Alexander or any of the other valleys that compose the viticultural north. Its crops are diverse, ensuring a dynamic agricultural identity. And it has yet to be significantly colonized by wealthy urban refugees seeking upscale ruralism and "wine country" lifestyles.

So is it unfair to invoke the North Coast while assessing the Salinas Valley's future? Not entirely. All wine regions share a certain socioeconomic dynamic. And just as Napa and Sonoma counties are closely aligned with the populous Bay Area, the Salinas Valley is close not only to the coast's vast tourism trade but also to the Silicon Valley pipeline. Of all the Central Coast's leading wine regions--the Santa Cruz Mountains, Paso Robles, the Santa Maria Valley and Santa Ynez--Monterey County shows the most potential for wine tourism and related traffic.

"A winery is a different animal than a lettuce-processing facility," Napa's Mary Handel says. "Wineries attract consumers. They generate traffic. Some would say that's good, because if we bring more people in, then our hotels prosper, more businesses come to town. But there are some negative aspects to tourism in agricultural areas, so I would advise caution."

In addition to general wine tasting, wineries can generate traffic related to on-site weddings, dinner parties and other special events. At a certain point, these activities can collectively generate significant growth in peripheral hospitality industries, furthering developmental pressures.

The lack of an initial long-term vision for managing such pressures has forced Napa and Sonoma counties into a painful process of reckoning, a process that has divided the local communities as they seek to balance the wine industry's commercial and economic opportunities with environmental impacts and local quality-of-life issues.

In 1991, Napa County enacted its "winery definition ordinance," a fractious edict that severely limits the retail and hospitality activities of all new wineries. In Sonoma County, the Planning Commission is reworking its zoning ordinances to cope with enormous changes that have transpired in its agricultural areas over just the past 10 years.

Surely this is a time for celebration, not panic, in the Salinas Valley. Still, Handel says, "We all know of places where the first few [tasting rooms] that come in are not a big issue, but then you start setting a tone for what you're going to allow. ... You have to ask, 'What do we want? What are proper and appropriate kinds of activities on our agricultural land?' You've got to look at the long-term integrity of the agricultural land and ensure that it's going to remain in agriculture, not be turned into a theme park."

BURNSTEIN SUGGESTS that the county should make life easier, not more difficult, for wineries. This, in turn, will provide a blueprint from which to build a balanced wine and tourism economy.

"We have to put some thought behind it, but positive thought," he says. Burnstein concedes that the valley's wineries should be "not all in the same place, not all on the same side of [Highway] 101, not all in one area."

Once a clear vision is established, vintners will maximize their positive impacts on the county. "Here you have South County with lots of land and lots of people looking for work," Burnstein notes. "And so everything the county can do to encourage this, I think, helps to balance the economy of the county and will improve the quality of life for everybody."

UC farm adviser Larry Bettiga adds that the agricultural labor force is enjoying increased stability relative to vineyard and winery development. He also says that farmland conversion is minimal.

"You'll never see the Salinas Valley become all vineyards," he says. "We've got a lot of climates within the Salinas Valley that just aren't conducive, especially the cooler ones around the Salinas. And the prime vegetable ground really isn't very good vineyard ground."

The conversion of undeveloped lands to vineyards clearly increases the county's aggregate pesticide load and runoff. But Bettiga says that the impact remains minimal in the overall countywide agricultural scheme.

"Generally, vineyards are pretty low input from the point of view of pesticide or fertilizer usage," he says. "They're among the lowest input compared to other crops that we currently grow in this area."

Things are also stable on the water front. "Grapes are extremely efficient water users," says Gene Taylor, senior hydrologist with the Monterey County Water Resources Agency. "They lend themselves to efficient irrigation practices. You're looking at water usage of something less than two acre feet per acre, whereas with row crops you're looking at two and a half to three acre feet per acre, depending on what part of the valley you're growing in."

Most of the county's vineyard development, Taylor adds, is taking place in "hydrologic subareas," where overdrafts are not a significant problem. "In areas where the grapes are being grown ... the overdrafts are minimal. Certainly it all adds to the problems in the northern part of the valley. But as long as we have water in the reservoirs and can make releases and recharge the groundwater basin, we will recharge as much as they can pump."

Despite the potential for developmental and environmental problems, much bodes well for Monterey County's wine industry.

"The potential is just now being realized," says Lockyard Vineyards' Steve Pessagno. "We're on the verge of breaking through, and right now we're just working real hard at trying to make it happen."

Acreage:

Average Price per Ton:

Total Market Value:

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

Monterey Vineyard Figures

1976: 34,855 acres

1987: 31,150 acres

1997 estimated vineyard acreage: 36,000

1987: $405.50

1996: $1,090.31

1987: $40.3 million

1996: $129.7 million

From the April 9-15, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)