![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

I Dream of Trinidad

Geoff Dunn and Michael Horne spent 3 1/2 years making the definitive documentary film on calypso music, and now it may be set to break wide open. Could 'Calypso Dreams' be the next 'Buena Vista Social Club'?

By Mike Connor

In 2002, a rough cut of Calypso Dreams earned the prize for Best Caribbean Documentary at the Jamerican Film Festival in Montego Bay. And when the movie premiered in Port of Spain, Trinidad, where it was filmed, the mayor declared the entire week "Calypso Dreams Week," urging parents to take their children to see this important documentary. Its popularity at the Mill Valley and Pan African film festivals has piqued the interest of international distributors.

So what else can you say about a film with this much street cred and critical acclaim?

Perhaps Crazy, one of the calypsonians in the film, put it best when he compared the filmmakers to the founder of Island Records: "What Chris Blackwell did with reggae," he told them, "is what you all are doing for calypso."

With distribution plans and a follow-up tour in the works, he may one day be able to say that what Buena Vista Social Club did for the old-timers of Afro-Cuban music, Calypso Dreams did for the venerable old stalwarts of calypso music.

In Calypso Dreams, which premieres at the Del Mar Friday, co-directors Geoff Dunn and Michael Horn--both of them stallions of Santa Cruz culture for decades--bring this vibrant folk music to life on the big screen with performances by and interviews with a host of calypso legends--most of whom are unknown on the international stage.

It's shocking to realize that the real story of calypso music has never really made it past the shores of the little dual island country of Trinidad and Tobago, where the music originated. Most filmmakers don't make it past the spectacles of carnival and steel drumming, and if they do, funding is a tricky thing for a film about a genre that many people associate with a single name: Harry Belafonte, no? The "King of Calypso."

But to say that Belafonte was the king of calypso is like saying that Ram Dass is the king of Buddhism, or that Ricky Martin is the king of Latin music. Trinidadians find the notion ridiculous. Belafonte himself denies the epithet in the film, revealing that it was foisted upon him by record producers at RCA without his consent

The music itself has spread around the world, in part via Belafonte, but also through calypso legends like Lord Kitchener and Mighty Sparrow, both of whom enjoyed more success in England than they did in the States. But the world was only getting the cherry on top of an art form with roots embedded deep in the culture of the Caribbean islands.

Now It Can Be Told

Calypso Dreams focuses on the true kings and queens of calypso, affording an unprecedented, intimate glimpse of a culture known to be distrustful of the Yankees' motives--and with good reason. The people of Trinidad and Tobago are mostly of African and East Indian descent, brought over by European colonizers as either slaves or indentured servants after the original inhabitants--Arawak and Carib Indians--were wiped out. Only in 1925 was partial self-government instituted, followed later by full independence in 1962.

Like the blues in America, calypso is a folk art born of the struggle for freedom. Some calypsonians like to call it a "poor man's newspaper" for the often topical editorializing going on in song. Unlike the blues, though, calypso is unwaveringly upbeat and humorous in expression, and the charisma of the men and women in the film is intoxicating. Gathered together in bars and living rooms, or singing in calypso tents or out in the street, the old-time calypsonians --with colorful sobriquets like Lord Superior, Mighty Sparrow and Lord Pretender--tell their story in their own words and songs.

And yet despite the cheery tone of the music, the words in the songs often cut to the quick. As David Rudder says in the film, "Behind the laughter there is always a blade." Similarly, the film is composed like a calypso--ostensibly light-hearted and fun on the surface, with magical and inspired performances by the old-timers throughout, but with an underlying narrative of the golden-age calypsonian as a dying, neglected breed.

The Dream Team

Michael Horne and Geoffrey Dunn have been friends for over 25 years. For the last 18 years, musician/promoter (and former owner of Palookaville) Horne has made the trek down to carnival, playing steel drums and even producing steel drum compilations on his Blue Rhythm record label. As early as 1987, Horne began cajoling Dunn--an experienced documentary filmmaker who lectures on the subject at UCSC and also serves as executive director of Community Television in Santa Cruz--to help him make a film about calypso.

"What struck me 18 years ago about the calypsonian and calypso culture," says Horne, "is that it is this forum where anybody in the community can have a voice about anything that they want to talk about amongst their peers--it's a very public forum. It's analogous to talk radio in this culture, or maybe writing a letter to the editor to the paper. In Trinidad, there are musical motifs that, if you can write a lyric about whatever it is that concerns you, you can get up in front of hundreds, maybe thousands of people and speak out. So I felt like, what we could to do bring some awareness to Trinidad and calypso was one thing, but more importantly was what Trinidad and that culture, that model for community, had to offer the rest of the world. I though it was really an interesting and a unique model for a public voice within a community."

Alas, the fairly substantial amount of funding for a film that documented culture rather than Harry Belafonte was all but impossible to come by at the time.

"We tried making the film, but there just wasn't any money for it," says Dunn. Everyone thinks Calypso is Harry Belafonte, but when you tell them it's this kind of ruffian, urban culture down in Trinidad, there was really no one who wanted to fund something like this."

Then, in 2000, the "Grandmaster" of calypso, Aldwyn "Lord Kitchener" Roberts, passed away. Both Horne and Dunn realized it was time to make it happen.

"In 2000, when Michael just got back from carnival--I was working here, Palookaville was still going, and I ran into him literally right in front of the Del Mar," says Dunn. "He told me that all these calypsonians had died. So there was this sense of urgency, and of course Buena Vista had just come out, so there was this kind of renewed interest in Caribbean music."

Dunn immediately got on the horn with his filmmaking partner Mark Schwartz, whose brother had some connections in Jamaica and Trinidad.

Filming the Impossible Film

By January of 2001, they were in Trinidad for their first shoot, and it started out a mess. The man they were supposed to film, Lord Relator, showed up late and forgot his guitar, causing them to cancel the shoot altogether. But the next day, he brought Blakie and the Mighty Conqueror with him to a pub for a "lime"--a Trinbagonian term for hanging out--and the crew caught on film a singalong scene with more magic in a single bellow of Blakie's infamously devious laughter than most films can hope to capture in their entirety.

"I realized two things that first day," says Dunn, "first, that it was going to be an almost impossible film to make. But I also knew from the scene we had filmed the very first day that if we could finish it, it would be a really great, engaging film."

Time and again, the interviews revealed the personalities and lasting friendships among the greats, and also yielded utterly charming examples of calypso music. Cinematographer and co-producer Eric Thiermann does an excellent job drawing the viewer into the film, providing scenic vistas of Port of Spain and taking the viewer right into the thick of Carnival, up and down the ever-bustling Frederick Street in the heart of town, and into the tents, cafes and homes of the calypsonians who live there. In an effort to move away from this Las Vegas-style of performance popular in calypso tents these days, the producers arranged intimate, acoustic settings, to great effect.

"We wanted to get the old-time presentation," says Dunn, "and I think the Hilton rooftop session with Mighty Sparrow and Lord Superior is a classic example. They go back 50 years together, and back then that's the way you presented the song. Those guys all came alive with that form of presentation. They weren't quite sure about it, why we would want it that way. But then they got into it, and these little limes we put together just became magic. That was universal."

Additional commentary from calypso historians/performers David Rudder and the Mighty Chalkdust give the film a lot of its shape with insightful commentary that touches on all aspects of calypso--from its historical and cultural significance to more specific issues like gender roles and, of course, the Harry Belafonte phenomenon.

Belafonte Speaks

A huge supporter of Barrios Unidos, Belafonte happened to swing through Santa Cruz for a benefit talk. Barrios Unidos of Santa Cruz founder and director Daniel "Nane" Alejandrez helped set up an interview for the filmmakers at the Darling House.

Horne says Belafonte was anxious to tell his side of the story.

"It's a fascinating interview," says Dunn. "He talks about having been a young boy in Jamaica with the Trinidadian calypsonians coming there, so it's not like he pirated this culture. It was part of his life, his culture, and he remembers some of the songs from the '30s. He's a student of the African diaspora, and his role, for 40-odd years, has been distorted."

Adds Horne, "It was neat to see that in Trinidad [the scene with Belafonte] has provided a sort of a healing for this old wound that goes in both directions. You can't help but love Harry--he's got a real love and admiration for the culture that certainly comes through."

Belafonte talked for over 45 minutes in the interview--of that, about two minutes of footage are in the film. But his scene was so well-received that Dunn and Horne plan to run the entire interview on television in Trinidad.

Not only does Belafonte finally tell the true history of the "king of calypso" title, he also talks about how for two years he wouldn't perform any of the songs on the King of Calypso album as a personal protest against his record label RCA, which had done the dubbing in the first place.

More than anything else, Belafonte comes off as knowledgeable and humble.

"What I did do," says Belafonte to the Trinidadians, "was to use the environment of Caribbean lore to put us on the map at another level that I thought was instructive and creative for us. And in that service if I have offended you, then I beg your forgiveness."

But as should be the case, Calypso Dreams gives the last word to the Trinidadians.

Says Mighty Chalkdust, "Belafonte put plenty of water in the brandy, that's all. He did not give us brandy."

Dying Kings

Widely known in Trinidad as the king of extempo (short for "extemporaneous," an off-the-cuff calypso similar to freestyling in hip-hop), Lord Pretender was in his 80s when the film was made. Dunn and Horne were fortunate to get a 90-minute interview with him on tape--he died, in abject poverty, in 2002.

"We're motivated by the old guys--that's the weight," says Dunn. "They've put their trust in us to carry their music and their story and their lives out into the world. And that's a big weight. I guess in terms of my film career, it's probably the biggest responsibility I've ever had. "

With over 65 hours of raw footage to work with, some of it the last that would ever be recorded, Dunn hammered out a rough cut in four days.

"That was the biggest intellectual challenge of my life," says Dunn. "The interesting thing is that Michael has this wonderful sensibility for staging a concert, and I'm into more structural narrative, so what we did was we completely blended the two narratives. We were able to do both, so it's structured as a concert, and structured as narrative."

Naturally, with Horne involved, there will also be a soundtrack, and once the movie gets full distribution, he plans to organize a tour with some of the key figures in the movie following its release.

"My 'calypso dream' is that the film introduces the culture to a global audience," says Horne, "but also provides a direct line to Trinidad and calypso and to these men and women in their prime and beyond their prime, and finally get these guys paid."

"What we want to see happen," agrees Dunn, "is the calypsonians get recognized, and that the music gets spread through the distribution of the film. Our goal is to get it out there and take care of some of the old guys. In Trinidad, there's a certain level of reverence for the culture, and a certain level of lip service being paid to it. There are old, legendary calypsonians who are homeless down there who live in absolute poverty. They have no support from the culture or the community itself--it's one of the great ironies."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

They Have a 'Dream': Left to right: Eric Thiermann, Michael Horne, Crazy and Geoff Dunn. Horne first suggested the idea for the documentary that would become 'Calypso Dreams' to Dunn in 1987.

Call Him Crazy: Crazy, one of the calypsonians featured in the film, says Horne and Dunn are doing for calypso what Island Records did for reggae--namely, giving it a deserving vehicle for exposure in the U.S.

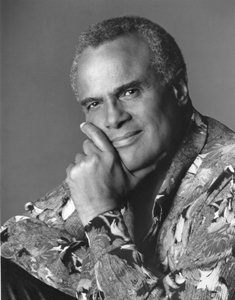

The Situation Gets Harry: Harry Belafonte made some startling revelations about his controversial past with calypso during the filming of 'Calypso Dreams.'

Calypso Dreams premieres at the Del Mar on Friday, April 11, at 7:30pm. Tickets for the screening and reception, which benefits the Elder Calypsonian Fund, are $12.

From the April 7-14, 2004 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.