![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Photograph by George Sakkestad Judging Laurie: Laurie Flower hugs her attorney, Tom Worthington, outside the courtroom after her sentencing. Flower & Child Laurie Flower had been a foster mom for 10 years. One day, she and a 13-year-old boy in her care began an affair that lasted 18 months. Thus began her slow descent into hell. By John Yewell 'HELLO, MY NAME is Laurie Flower." That was how the email began, arriving late on the night of Jan. 29. The day before, the state attorney general's office had confirmed that a deal had been struck with Peter Chang, Flower's former attorney. Chang, a former Santa Cruz County district attorney, had faced a total of six felony and misdemeanor counts for his alleged role in a plot to hide a key witness in a child molestation case against Flower. Now it appeared Chang, 62, who was a candidate in the March primary for the job he last held 25 years earlier, would plead to a single misdemeanor of violating a court order. Although he still faced the possibility of disbarment, he wasted no time hitting the campaign trail. Flower, meanwhile, still faced jail time and a lengthy probation, if she was lucky. But Chang's handling of her defense had become an issue that, strangely, was having a more negative effect on the DA's office than it was on him. Thanks to Chang's involvement, her case became a political football in the high-stakes election, receiving more publicity than it might otherwise have garnered. Now, the woman at the center of a legal case that threatened to bring down the district attorney wanted to talk. "I think its time for the real truth to be told. Befor someone actually votes for him, and he dose what he did to me, to someone else [sic]." She agreed to speak honestly and answer all questions. The only stipulation agreed to by Metro Santa Cruz was that the article would appear after her sentencing March 17. In an exclusive interview conducted over several weeks of visits and phone calls, Flower goes public for the first time, discussing her relationship with Matt (because he is still a minor, his name has been changed for this article), the 13-year-old foster child with whom she has been convicted of having a sexual relationship. She speaks frankly of her responsibility for her actions and her anger at her former lawyer, which were the basis for the positions and facts that arose during her appearances in court and the investigation of her case. She also tells of how she and her family have coped with criminal charges brought against three adult men who sexually assaulted one of her daughters while Flower herself faced charges. Peter Chang was also contacted, and responds to several of Flower's assertions.

Outcomes: For Laurie Flower, love was no defense.

Character WHAT ARE WE TO make of Laurie Flower? Over two months of getting to know her for this article, a complex picture emerged. Flower carried on her affair with Matt for 18 months. Now a convicted child molester, Flower is reminiscent of Mary Kay Letourneau, the Seattle teacher who fell in love with a 13-year-old student in 1996. She is timid and so eager to please that she even speaks highly of the assistant district attorney, Pam Kato, who convicted her. Aggressive, a word Chang once used to describe her, hardly comes to mind. Flower (who has been married three times and is currently divorced) is herself the mother of two teenage girls, trusting to a fault, certainly naive--a womanchild who artlessly confesses that what she did was wrong. "I was a foster mom. I'm supposed to give kids a mom's kind of love," she says in a phone conversation. "But I fell off the track." But her continuing professions of love for the boy, now 15, belie her contrition, revealing a purblindness to the line she crossed from parent to peer. Complicating the debate is the opinion of some that society rejects the possibility of such relationships not because they are impossible, but to achieve another goal: to erect a wall of taboo to protect children and adolescents from predators. Flower expresses frustration with a world that rejects the legitimacy of what she says she feels in her heart for Matt. "It was like a real relationship," Flower says. "He's not like a child. He never was. He doesn't look like a child, he doesn't act like a child. He is very much in his mind an adult." Perhaps the most apt description of Flower herself was uttered by her second attorney, Tom Worthington, in his appeal for leniency at her sentencing before Judge Heather Morse three weeks ago. "She saw herself as a teenager in a woman's body, and the young man as a man in a teenager's body," Worthington said. "She was a teenager in love." A court-appointed psychologist said that Flower, now 40, is no pedophile, but rather a woman with a dependent personality disorder who suffers from very low self-esteem and chronic low-grade depression. In other words, Laurie Flower is no Mrs. Robinson.

Background FLOWER AND MATT became sexually involved a few months after he was placed in her Corralitos home by welfare officials in the summer of 1997. He had just turned 13. "He became kind of flirty," Flower says. "I didn't think anything about it until one night he kept trying to kiss me and I kept saying no. Eventually, I kissed him back." Their secret began to unravel late in 1998. Matt moved out in November, and a few weeks later went to live with an uncle in Ventura, to whom Flower signed over custody rights. "We knew that we were not going to be able to stop if he was in my home," she says. "In the paper it said that he was taken out of my home when they had an idea what was going on. That's not true. He was caught drinking. He was starting to get into trouble and I couldn't control him or keep him out of trouble. The agency that placed him there thought that it wouldn't be good for him to be in my house anymore." Flower does say, however, that a social worker made inquiries at this time about their relationship, but nothing came of it. Soon after Matt moved to Ventura, he apparently began to talk--adolescent bragging, perhaps--about his relationship with Flower. She says his uncle and grandmother got wind of it, and soon word got back to authorities in Santa Cruz County. In mid-March, 1999 Flower was served with a restraining order that prevented her from seeing Matt. With further legal action looming, she looked through the Yellow Pages for an attorney, and found the name of former DA Peter Chang. She hired him. Very soon after their first meeting, says Flower, Chang began to act strangely. Flower: He was weird. I've never had to deal with somebody like that before, I mean an attorney, so I didn't really know what to expect from anybody. I thought he was being very kind, you know what I mean. He kept wanting to meet me for meetings, like right after my work, which was at 9 o'clock at night at Tiny's. A couple of times after I saw him he went to give me a hug, and I thought he was just going to hug me, and he kissed me. He kissed you for real? Flower: Yeah. And I felt kind of weird about it. From day one he went on and told me about how he could save me, that he is the ex-DA, he told me about all these cases he had, and still has, that he's getting people out of. He talked about himself a lot. ... I felt like my life was in his hands. That was only the beginning, Flower says. She began to suspect Chang wanted to be more than her attorney. "[A]bout three times a week, he wanted to see me. ... At first he wanted to start going to lunches, and so we had lunches out. He had me meet him at like restaurants and stuff. Or I'd meet him somewhere and he'd pick me up and take me to restaurants." She also says she felt he was jealous of her feelings for Matt. "I think it bugged him that I loved Matt. He used to tell me all these bad things about him. And it got me kind of sad." Meanwhile, as the investigation moved forward, Flower says Chang repeatedly assured her that he and only he could keep her out of jail. Taking Advantage FLOWER WAS ARRESTED on April 19. Shortly afterward, she went to Chang's house for the first of what she remembers as half a dozen meetings there. Eventually, Flower says, Chang coerced her into a sexual relationship, which she says began on her second or third visit to his home. She says there was a second sexual encounter there about a month later. Both times Flower claims she woke up in his bedroom, with Chang having sex with her. Flower: [H]e told everybody things that [Matt] doesn't love me, doesn't care about me, wants me to be in prison, thinks I'm a horrible person. And he just kept going on and on like that. And then I had another drink. This drink was weird. What do you mean by that? Flower: It was really strong, but it numbed my gums and was just weird. I asked him how come it's numbing my gums, and he said it was probably the dish soap. The problem was, she realized later, this was her second drink from the same glass--and the first drink had not had the same "weird" taste. "[He] put some ...he had like a lemon juice container and kept putting lemon juice in it. ..," she says. "I just felt really drunk. And then I went and sat on the couch, and I don't remember everything after that." Special Agent Ron Ward with the state Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement in San Jose, an expert on so-called date-rape drugs, says the symptoms Flower claims she experienced--numbness, blackouts--are "consistent with GHB," one such drug. (There is no Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement investigation of Chang.) Chang admits he had a sexual relationship with Flower, but says it was her idea. "The sexual relationship came very early on, when I met her. And it was over very early on," he says. "Also, as far as I'm concerned, she's a nymphomaniac. She was the most aggressive female I have ever run into." As for the implication that something may have been added to her drink, Chang says he put lemon juice in the vodka, but nothing else. "You're inferring something that's totally not true. I didn't put a goddamn thing in her drink," he says, adding that he doesn't even know what GHB is. Then the lawyer adds: "That girl didn't need anything put in her drink. She didn't even need a drink if you wanted to take advantage of her." After the second sexual encounter, Flower says, Chang made an admission. "He said to me, 'What would you do if I fell in love with you?' And I told him don't, 'cause I'm not capable of loving you. Those were my exact words. ... I just remember crying. And he let me drive home that way. I don't want to remember that." She says that Chang also claimed to have slept with most of the female employees of the district attorney's office, and at least one reporter.

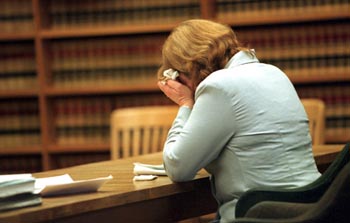

Court Ritual: Flower broke down in court during her sentencing when it was revealed that Matt, through prosecutors, had requested one more meeting with her. Judge Morse denied the request. Closing the Net ON JUNE 4, MATT ran away from his foster home in Ventura. Flower says Matt called her house when she was not home and told her daughter that he wanted "to make things right," and that he had never said any of the things Flower says Peter had told her. "[T]hey talked and figured out Peter was lying the whole time." At this point in our conversation, Flower stops for a moment. Whenever she's thinking about Chang, a certain sour look comes over her face. Several times Flower breaks down when recounting her relationship with her lawyer. "He's just a sick man. God he's such a sick man," she says at one point. At another, she cries and says, "I hate him." Later in June, Matt arrived in town and called Flower. She says she asked Chang if she could see him--despite the court order. "Peter told me if he called it was OK to talk to him as long as I don't call him," she claims. Following that advice would lead to an additional 16 misdemeanor counts of violating a court order, although Judge Morse would later tell Flower she could not blame that on Chang. A few days later, Chang arranged for Flower and Matt to be together one more time. This violation of the court order is the only count of the original indictment that Chang has admitted to. Then, Flower says, Chang arranged for Matt to go to Hawaii in order to avoid testifying against her. "[H]e came back up and he had a lot of money, like that [indicates size], tossed it at me, and said, 'Here, he's going to Hawaii.' And I said, 'What?' And he said he was going to Hawaii, that way he can't testify against me. Matt came in and gave me a hug, he said he might be going away for awhile." Chang would later be charged with one felony count of dissuading a witness, which was dropped as a part of his plea bargain. He denies helping Matt go to Hawaii. "There was no reason why I should make the kid go anyplace to disappear," Chang says. "It wouldn't have helped the case." He says he first learned Matt was in Hawaii on July 14, when investigators found the boy there. "I had no idea he was in Hawaii." Over the Fourth of July weekend, Flower and Matt stayed together in a Santa Clara motel before he left. Flower says she begged him not to go, but that Matt said Peter had assured him that it was for the best. "I think [Peter] didn't like the unconditional love that I was able to give Matt. I love everybody. That's just the way God made me. I think Peter knew that and he tried to ruin that. But it didn't work." When Matt's whereabouts were discovered, he was returned to Santa Cruz, this time in custody. On July 26, sheriff's deputy Phil Wowack arrived at Flower's home with a search warrant. Flower was out, but her panicked daughter called to tell her they had come to arrest her. Flower called Wowack, promised to turn herself in that day, then called Chang. There followed a crucial meeting in Chang's car, when, Flower says, Chang tried to cobble together a story. Flower says Chang convinced her to take responsibility for trying to hide Matt from the authorities. He had to stay out of jail, she says Chang told her, in order to continue fighting for her freedom. Flower: [H]e just basically told me, OK, he'd figured it out, that I have to, um, tell them that I did everything, and he'd get me out of this. What did he mean by everything? Flower: Hiding Matt, paying for the ticket, telling me where to stay at a motel, giving me all the information for the ticket. Everything. And he said that's the only way he could get me out of it 'cause he wouldn't be able to get me out of it from in jail and that nobody else would be able to. In other words, he asked you to protect him? Flower: Yeah. He said he had to trust me. Then, Flower says, Chang promised that if he had to tell the truth to keep her out of jail, he would do so. "He said that we might have to get married so we don't have to testify against each other. I just kind of was like, you know, I didn't say anything. I didn't want to get him mad either. I go, 'What if I have to go to prison?' He goes, 'I can't let them do that to you. You won't have to go to prison.' And I said, 'Will you tell the truth? Will you tell the truth if I have to go to prison?' And he said, 'Yeah,' 'cause he wouldn't allow them to put me in prison." Flower says Chang played on his credibility--and her lack of it--to cover for him. "He said that everyone will remember that he was the [former] DA, and why would he lie, and why would they believe me over him," Flower says. "He was going to be public and so that way he'd get the sympathy of the community, whereas I was this child molester, and no one will believe anything I say." He didn't threaten her, Flower said. "I was already afraid of him. He didn't have to." But she says he did try to sweet-talk her. "He said, 'I can't get you off from in jail.' And he basically said that I can get your freedom. He just kept telling me, 'I can make sure you're free.' You know, he just kept saying, his head cocked to the side, 'I really trust you, Laurie, I really care about you, Laurie, I really love you, Laurie.' " Flower says she tried to take the fall, but she stumbled on the details, such as where she got the money. Authorities weren't buying her story. "She was a poor liar," says DA investigator Joe Henard, who was present. He also says the timing of her admissions, coming after Matt had returned and fingered Chang, suggests she was covering for her attorney. "It wasn't until Peter knew he was under investigation that he encouraged her to talk," Henard claims. "Peter's guilty and he knows it," "Absolutely untrue," Chang said, when asked whether he induced Flower to lie to protect him. "I advised her when we went to the sheriff's office that the only thing that was going to be reasonable to do at the time would be to admit to everything we knew they'd be able to prove that she did." One of those things, he said, was that she bought the tickets with her own money from Tropicana Travel in Watsonville. As for the money to pay for the tickets, Chang claims: "She had sources of income that nobody made any inquiry about." Nonsense, says Flower. She couldn't even afford her bill to Chang. Her parents paid it for her.

Thinking Back: Laurie Flower was in a reflective mood during our first interview. Beginning of the End NEAR THE END OF JULY, the wheels came off. The DA's office declared in court that it suspected a conflict of interest for Chang, and the headline the next day blared: "Ex-DA Under Scrutiny." Chang was removed as Flower's defense counsel, replaced by Worthington. Only then, Flower says, when she was no longer dependent on him, did she allege to authorities, on Worthington's recommendation, Chang's involvement in Matt's flight to Hawaii. And she spoke, confirms Worthington, without any promise of a lenient sentence. The interview with prosecutors took place Aug. 6. After her admission, Flower took, and passed, a lie-detector test. A plea bargain followed four days later. Flower pleaded guilty to one felony and two misdemeanors, with sentencing deferred. A second felony later drew a suspended sentence. She also pleaded guilty to one misdemeanor count of dissuading a witness and one of 16 misdemeanor counts of disobeying a court order. The timing and sequence of events is important. Chang's attorneys and supporters of Kate Canlis, the third candidate in the race for DA in the March election, accused Flower of selling out Chang for the promise of a lighter sentence. Because she did talk without promises of leniency, that argument falls apart. At the time of his arrest, Chang's attorney, Paul Meltzer, tried to turn the tables on Flower. "The lesson of the Flower case," Meltzer told the press, "is that an accusation against your lawyer is a get-out-of-jail-free card." Of course, Laurie Flower saw it all differently. It was Chang, she claims, who set her up to take the fall--at least for the charge of dissuading a witness--not the other way around. With Chang emerging as a suspect, the case began to catch the public's attention--and things began to move quickly. On Aug. 4, the same day authorities served a search warrant on his house, Chang announced his intention to run for district attorney. Flower pleaded guilty Aug. 10, and on Friday the 13th, Chang was booked. The following Monday he was indicted on the first of what would become six counts, three of them felonies, including dissuading a witness, inducing testimony and violating a court order. But the case didn't really become an election issue until DA Ruiz noted in an interview that a "genuine attraction" existed between Matt and Flower. What he meant is that such an attraction made prosecution problematic because of the difficulty in getting the "victim" to cooperate with prosecutors. But the public, with the help of his political opponents, interpreted Ruiz's remark as condoning the relationship. Canlis seized on the comment as evidence of Ruiz's unsuitability for the job. The conflict of interest created by Chang's candidacy later resulted in the case being taken over by the state attorney general's office. Many have speculated that this was Chang's strategy all along--a charge Chang denies. "I have no friends in the attorney general's office, period, and no influence with that office," Chang insists. "And I don't know people in charge of my case. Absolutely no influence was used." But Flower says Chang spoke about the AG's office, suggesting that he had connections there. Flower: He said if you can get a case to the state general attorney's [sic] office, that you're going to win. In fact, he was trying to figure out ways to get my case out of there. And when he ran for DA did you make the connection between the attorney general's office and ... Flower: Yeah. Because he knows people in there. But did he mention any names? Flower: No. He wouldn't tell me any names of people there. He suggested he knew people who could help him? Flower: He told me he knew people everywhere. In high places and low places. And you just always repay your debts. I remember him telling me that. You see, Peter also bragged about himself all the time. And at first I believed everything he said. With or without Chang's entry into the DA race, his political prominence probably would have cast an unwelcome light on her case. But there seems little question that Flower became a pawn who was sacrificed on the altar of political expediency. And while she faults Chang, she also points a finger at Canlis, who made the case one of the pillars of her campaign. "Kate Canlis," Flower says, "used me against Ron Ruiz." Trial and Error AS CHANG'S JAN. 25 trial date approached, Chang faced prosecution on three felony counts: dissuading a witness, inducing Laurie Flower to lie, and secretly tape recording a conversation with Flower. He also faced three misdemeanors: inducing testimony, violating a court order, and giving false information to law enforcement. Deputy AG Jerry Curtis, who was in charge of the case, was handling a death penalty case in Alameda County at the same time. Unprepared for the Chang trial, he sent Deputy Attorney General Bud Frank in his place to a trial-readiness conference the Friday before to ask for a delay. But Curtis had missed the deadline for filing what is known as a Form 1050--a motion to continue. When Chang's defense attorney refused to waive his client's right to a speedy trial, Judge Heather Morse denied Frank's request for a continuance. "You just don't go to a trial-readiness conference and ask for a continuance," noted one local court observer. Faced with going to trial, the AG's office settled for a guilty plea on a single misdemeanor count of violating a court order. "It's fair to say that we failed to make a timely request," says AG spokesman Nathan Barankin. The plea bargain, he insists, was not the result of being unprepared to go to trial. "It doesn't mean it was under duress or that we were forced to deal." Chang denies there was anything other than the facts of the case that influenced the plea agreement. "They looked at the allegations and said, well, on the face looks like a pretty good case," Chang explained. "Then looked at the rest of the evidence and said, the boy [Matt] has been caught in 17 different lies, and what Laurie has to say can be proven and would be proven to be untrue by the evidence." The plea bargain, with announcement of its terms put off until after the election, reopened political wounds that had festered since the previous fall. Even though the DA had no say in the plea agreement, the local daily paper called the case a "political deal." What the public never really understood was that within the legal community, Chang's alleged actions are considered among the most serious an attorney can commit. In an op-ed piece about the attacks on Ruiz, published Dec. 12 in the Santa Cruz County Sentinel, retired state appeals court justice Harry Brauer wrote that "it is a perfectly appropriate exercise of prosecutorial discretion to offer a plea bargain to the client in order to nail the lawyer, because a higher standard of conduct is demanded of officers of the court than of the ordinary mortal." Attorney Ed Frey, who is handling a civil suit Flower has filed against Chang, is also, understandably, less charitable about Chang's handling of Flower's defense and the events that led to Chang's indictment. "He led her down the primrose path," Frey says. "She told him from the outset that she was guilty, but he had his own agenda that led him to manipulate the situation and caused her to get involved in further criminal activity--dissuading a witness and violating a court order. "His duty as an attorney totally broke down. He had his own sexual designs." As Flower put it: "There were no lines anymore. There were no boundaries." Frey says that had Chang advised her to throw herself on the mercy of the court early, after Matt's statements to friends resulted in her arrest, "there would have been a good chance of her avoiding jail." And there almost certainly would have been less publicity. Statutory Flap ONE OF THE THEMES that came up repeatedly in our discussions was how much Flower felt that her being a woman resulted in, if not harsher treatment, at least harsher publicity. If it had been a 13-year-old girl and a 39-year-old man, would the law have prosecuted more vigorously? "I would say, 'Bullshit,' " Flower responds, citing several recent news stories about men getting lighter sentences. She mentions the case of Jeff Winterhalder, the scion of the family that owns North Bay Ford, who got 60 days in jail and three years of probation for the statutory rape of two 17-year-old employees, and who didn't have to register as a sex offender. He was arrested last Aug. 31, about the same time her case was receiving so much publicity. "I'm getting the publicity because I'm a woman and it's a boy," she insists. "What happened to all these men? They get one page for the day and they don't even get the first page. I was all over the front page. And then they go and forget them because that's something that's done every day, and I'm not. I'm one of those rare cases where it comes out. And this was the real relationship. It may not have been right. "Everybody thinks I'm this horrible monster and a bad mom. I'm not a bad mom. I'm a good mom. I love my kids more than life. I'd die for any of them. And that's the same for Matt." Then Flower pauses for a moment, swallows hard, chokes up for a moment and asks if we can go off the record. I tell her that if there's something she doesn't want to be on the record, she probably shouldn't tell me. She decides to go ahead. "A few months ago, my daughter, she's 14, was raped by three men. She went to this party, and these men bought her tequila. I think two were like 20-something and one was like 30. She drank almost the whole bottle and she's taking medication too. She could have died. "She ended up coming home about two that morning. And she was drunk as a skunk. She was just torn up. Her hair was a mess. This boy brought her home. He told me there were condoms all over the place, that it looks like something happened. And I just kind of flipped out. "I went to talk to her and she was just out of it. And I told her I'm going to take her to the hospital, 'cause she was crying, and she said, 'Mommy, I told them no. I told them no, Mommy, and they wouldn't listen.' When she's tired and she's upset she talks like a little baby." Three men in their 20s were ultimately charged (see "The Sentences" page 8). None will have to register as a sex offender, as Flower did, and two of the three got shorter jail terms than Flower. Flower sees this as further evidence of a double standard. "I don't ever want to hear again how, if it was a man, instead of a woman ..." Flower characterizes the incident as a gang rape. "This is not, like, a relationship. I mean, I know mine wasn't right, and I admit that. I mean, it's not legally right and it's not morally correct, but it's real. What they did was for their own selfish wants, needs and desires. What I did was because it was a feeling." In the wake of the assault, Flower says her daughter has continuing nightmares. "Saturday, I stayed up till two in the morning holding my daughter who was crying, just sobbing like you would not believe, tears running down, because she thought something like this was going to happen to her sister. She's not going to be able to protect her sister. She thinks it's going to happen to her friends. She thinks it's going to happen to me. I had to hold her in my arms until she stopped, until she fell asleep. And this is how I live my life now."

Getting to Acceptance: Flower turns to look at family and friends in the courtroom, who came to support her during her sentencing. The Aftermath THERE ARE SEVERAL parallels between the Flower and Letourneau cases. Both women were in their mid- to late-30s when the affairs began. Both involved 13-year-old boys over whom they exercised authority. Both claimed a deep love relationship and both boys claimed they had suffered no psychological harm. Flower's affair even started in the fall of 1997, at a time when Mary Kay Letourneau sat in a Seattle jail awaiting sentencing. Perhaps most significant, both cases have caused emotional debates over the influence of gender in the assignment of blame in sex crimes, the limits of affection between adults and minors and attitudes about youth and crime. Regarding the latter, Flower's attorney, Tom Worthington, drew attention to the recently passed Proposition 21, the juvenile-justice initiative, at her sentencing. "When they act like adults, we now say they should be treated like adults," Worthington said to Judge Morse, pointing out that 14-year-olds can now more easily be tried as adults. "Yet in this kind of crime, we treat them like children again. Which is it? There is no reconciliation of those two views." Prosecutor Pam Kato countered that even though she agreed that Flower was not a pedophile, she was a foster mother, and "the most reprehensible part of this is the broken trust." In the final analysis, Judge Morse found the sentencing decision to be one of the most difficult she has ever had to face. "In 20 years, I've never seen a case that met the parameters of this particular case," she remarked. "It is difficult to determine where the balance should be. "I do believe Mr. Chang played a significant role in misguiding her," she continued. "But [Matt] was a ward of the court and needed to be in a sound parental environment. He badly needed parenting." Matt's protestations of love notwithstanding, Flower violated the law, Morse said, "whether [Matt] believed it or not." Morse added that Matt doesn't likely appreciate now how he will later be affected by what happened to him. Meanwhile, Morse admonished Flower to change the way she thinks about Matt. "I believe she continues to romanticize the relationship," Morse noted. "She must change her view of the relationship. ... this is not a Romeo-and-Juliet situation." "I think she's a pretty fair judge. Fair but tough," Flower said outside the courtroom. "The only thing I don't agree with is being jailed. She didn't say anything that was not true." Not even the part about "romanticizing the relationship"? "I'm thinking about that one still," Flower said, pausing to think. "I may not be able to see him and I won't, but you can't take your love out your life. It's hard to say I'll stop loving somebody." Laurie Flower begins her one-year jail term May 1. While she is in custody, her parents, who have supported her throughout, will care for her two daughters. Flower is scared--for herself, and the impact jail will have on her family. "You keep saying that readers might [be] skeptical. Nobody knows what kind of hell I've been going through. ... I don't want to go to jail. I don't want to go to prison. I'll die." [ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the April 5-12, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Spare Chang: Former DA Peter Chang had a relationship with client Laurie Flower at the

same time as he was defending her against sex charges. He also hoped to regain his old job in

the March primary.

Spare Chang: Former DA Peter Chang had a relationship with client Laurie Flower at the

same time as he was defending her against sex charges. He also hoped to regain his old job in

the March primary.