![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

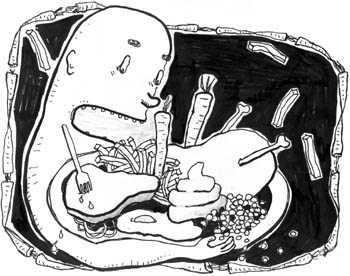

Growing Discomfort

Comfort food--the couch potato of cuisines--reflects the demise of taste, creativity and culinary adventure

By Christina Waters

NOT TOO MANY years ago, when Generation X turned to Y and Bubba made a killing on dotcom stock, the dining world lost its marbles. Suddenly, restaurants famed for well-crafted dishes with ethnic influences began expanding the size of their portions.

Fewer ingredients, but much, much more volume (i.e., stuff) appeared on the plates. In fine dining establishments, mashed potatoes popped out like oozing boils--soft, white cushions of flavorlessness. Italian and French restaurants, from trattorias to white-tablecloth bistros, purchased larger and larger plates, bowls and dishes. Portions ballooned up to fill those larger and larger plates, bowls and dishes.

Eventually, steak houses caught on and started serving their hungry diners hefty platters containing only a single item--a steak the size of Omaha. Accompanying these bovine monstrosities were equally large plates holding the soft, white pillows of potatoes that--overnight!--had become a requirement of every menu in America.

What had gone wrong? What had happened to the idea of going out to a restaurant for foods you couldn't make at home? Suddenly, it was mashed potatoes everywhere. Mashed potatoes with their skins on--the healthy, designer approach to a mindless dish. Mashed potatoes with a reduction sauce--the fattening, designer approach to this no-brainer classic.

Then it was garlic mashed potatoes. We watched, horrified, as restaurant after restaurant sprang up hopelessly devoted to what was essentially diner fare in fine-dining drag. Entire menus were built around garlic mashed potatoes. Ethnic be damned, these menus seemed to say, America craved good old-fashioned American comfort food.

Comfort food. Mashed, soft, textureless, often flavorless stuff that re-created (Oh, my God, I get it!) the food we were fed as babies. Mashed potatoes = mother's breast. A Freudian thing was happening, absolutely.

COMFORT FOOD. The idea suggests that the New American restaurant patron is psychically uncomfortable, suffering perhaps from existential discomfort. Food, the final frontier of legal sedation, was to provide what Paxil and talk therapy couldn't.

Comfort. The implication was that we no longer asked food to challenge our taste buds, to take our senses for a ride. No indeed. Comfort food popped up as a response to our neoadolescent need to go dumb, limp, soft. The middle-aging of the Baby Boom generation was not a pretty picture.

In place of the heirloom vegetables that provoked our intellectual curiosity and took us for a flavor ride, diners craved the known, the predictable, terra firma. Exploration was out--okay, maybe there were one too many world-fusion dining disasters. Safety was in. Safe food in an era of safe sex.

The glut of comfort food parallels our intellectual softening (viz., the current resident of the White House), a slackening of inquiry. It was inevitable. After all we'd cruised the waves of fiery Thai cuisine, surfed the edges of the raw and the spicy at any number of sushi bars and gone to great lengths for authentic molé and cochinita pibil. The collective appetite had OD'd, had just plain grown dull. And if dullness craves anything at all, it craves comfort.

Feeding into this puerile lowering of culinary attention was another factor: the fast-food factor. Restaurants were increasingly catering to Gen-Xers and their progeny who'd been raised (though that is too good a term for the latch-key syndrome) on Big Macs, Taco Bell and KFC. Big, soft, nonthreatening (Ha! Just ask your cardiologist) substances dripping fat and salt. Packaged in big, soft portions to be washed down by Cokes large enough to drown in. Malls of America sprouted Dunkin' Donuts faster than you could say "Jenny Craig." Soft, comforting doughnuts.

The pathetic craving to fill up the emotional emptiness within spawned its obvious conclusion: icky sweet desserts like the ones Midwestern grandmas used to make. Instead of some intensely focused lemon tart with intricate pastry crusts, bread pudding began encroaching on the former gooey, soft territory occupied by tiramisu. So wildly popular was this Italian deconstruction of mascarpone cheese, chocolate and whipped cream, that it was made the very backbone of late-20th-century cuisine. Smug in the knowledge that they had the fashionable dessert on their menu, some restaurants mailed in the rest of the meal. The tiramisu would do it, they thought. And--with a little help from the marginally more interesting cliché crème brûlée--it almost did.

BUT THAT WAS THEN. Now even God won't forgive the menu that fails to list bread pudding. The reason is as simple as the dessert itself. Almost any construction of bread plus sweet plus soggy will pass for bread pudding.

You just can't hurt this idiotic creation that turns grown men into 2-year-olds. Add ice cream--great. Throw on some whipped cream--even better. Today's hottest restaurants go the distance and offer the "Bread Pudding of the Day."

Given the opening, ice cream and chocolate desserts pushed their cloying way back onto menus. Desserts designed by and for children were now commanding $7.50 a bowl. Forget precise texture. Desserts now numb. Meal closure = mind closure.

Ice cream. Stale bread soaked in butter and booze. I could do that at home. Yes. That's it. For the video-rental generation who find it a hassle to actually get dressed and go out to a movie in a theater, the restaurant has now become an extension of the home. The irony of the phrase "homemade" fails to compute. Imagine training at a culinary institute only to become famous for the softness, the sheer innocuity of your mashed potatoes.

Someone is taking us for a ride. And consumers appear too stupid, or pliant, to care. Restaurateurs are opening a container of gelato and charging you $7 a scoop. A steak is thrown on the grill. Notice the words "wood-fired" popping up frequently? That "wood-firing" is the value-added feature of an otherwise run-of-the-mill grilled steak. A grilled steak with, of course, those de rigueur mashed potatoes.

Those potatoes take very little skill to prepare. Throwing a steak on the grill similarly takes little educational grooming. Yet you, the consumer, are paying anywhere from $25 to $35 for the privilege of eating something in a restaurant that your mother used to make every Saturday night.

When I go out to eat, I want something special. I want to be taken on a bit of a culinary journey, where I meet not only the delicious and the satisfying but also the new and unpredictable. I am not prepared to spend $100 for a dinner for two that I could have whipped up with the help of Safeway and a Weber barbecue. I want to be interested, even intrigued.

Like a few other nonslobs, I long for flavors that are subtle or unusual, for styles of preparation that show invention and skill. Ideally, I'd like to come away with a bit of healthy amazement. I want edge, not the edible equivalent of a La-Z-Boy recliner. Boy, am I on the wrong planet!

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Illustration by Sacha Eckes

From the April 4-11, 2001 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.