![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Rugged Individualist

Instrument-builder, activist and mountain man Bill Colvig lent a quiet presence--and wry humor--to classical music and gay-rights causes

By Leta Miller

FROM HIS EARLIEST years up to his death last week, Bill Colvig remained a country boy at heart. Despite two world tours, numerous radio and TV interviews, and appearances with Lou Harrison (his partner for 33 years) in some of the most prestigious concert halls in the nation, Bill's greatest pleasure still lay in communing with nature. A long-standing member of the Sierra Club, he treasured his daily walks from his home at the top of Viewpoint Road down to the flats of Aptos Center and back up the steep incline. Even after undergoing two knee replacements, he talked to me in the hospital about his dream of resuming his mountain-climbing adventures. Thus his long illness, which began with these operations and stretched through a series of increasingly acute ailments into a prolonged period of forced inactivity, was like a death sentence for the rugged outdoorsman.

William Colvig (b. 1917 in Medford, Ore.) was nothing if not an individualist. He cared little for social convention, even less for personal acclaim. He devoted his life instead to a few chosen passions: music, instrument-building, acoustics, gay rights, ecology and meaningful human interaction.

Bill's father first stimulated his musical talent. A bandmaster in the tiny town of Weed, Calif. at the base of Mount Shasta, Donald Colvig made sure his sons were musically educated. Bill played piano, trombone, baritone horn and tuba. In 1934 he matriculated at the University of the Pacific on a music scholarship, but soon changed his focus to electrical engineering. After transferring to Berkeley in 1937, he tired of the academic life and moved to Fairbanks, Alaska, to indulge his love of the wilderness. There he played baritone in the town band.

By the 1960s Colvig was working as an electrician in San Francisco, satisfying his musical curiosity vicariously by attending concerts of new and unusual music. In February 1967 he was in the audience at the Old Spaghetti Factory for a performance of Harrison's innovative theater kit, Jephtha's Daughter. The two men met after the concert and within an hour had discovered mutual interests in music, acoustics, aesthetics and politics. Both, for instance, were early supporters of Berkeley's nonprofit radio KPFA (founded in the 1940s by pacifists)--an electronic gadfly that had no hesitation about broadcasting controversial viewpoints. Likewise, both were members of San Francisco's Society for Individual Rights (S.I.R.), established in 1964 to promote gay rights.

In a matter of weeks Colvig had joined Harrison in Lou's tiny cottage in the Aptos woods. "It was my lifelong dream," he joked when I interviewed him in 1995, "to live in a little cabin out in the woods with a dirty old man. I'm joking, of course. Lou wasn't dirty. The cabin was, though, and I could see he needed some help."

OVER THE NEXT quarter century, Colvig helped out in far more significant ways than cleaning the cabin. He immediately became absorbed in Harrison's musical projects in tuning and instrument-building. A skilled craftsman, Colvig soon began constructing instruments: harps, plucked and bowed strings, and most importantly, metallophones. These he tuned to Lou's specifications, at first by ear ("Lou's ear," Bill hastened to add) and later more precisely with an oscilloscope he assembled from a $90 kit. The small projects soon grew into a larger one: constructing a set of keyed metallic instruments hit with various types of mallets and tuned in pure interval ratios specified in ancient Greek theoretical sources. For the keys of the various instruments, Colvig used aluminum slabs or steel conduit tubing. As resonators for the larger instruments he chose #10 tin cans. When Harrison expressed an interest in adding gongs to the ensemble, Bill put in a call to the Crystal Ice Company in Watsonville in search of empty oxygen tanks. "'Sure, we have a few discarded ones,' they told me. I bought three or four, and we cut them to random lengths and suspended them from a wooden rack. We hit them with baseball bats and they made beautiful inexpensive gongs." When their new percussion orchestra was complete, Harrison and Colvig dubbed it "an American gamelan" after the traditional Indonesian ensembles Harrison had first heard in the 1930s.

In later years Colvig would build two more full gamelans with Harrison: one for San Jose State University and one for Mills College. When the two men purchased property in the late 1970s to build a new house, Bill designed a dwelling featuring a large open studio that could house their many instruments and could serve as a gamelan performance space.

Through all of this musical activity Bill maintained his support of ecological and humanistic causes. In 1978 he and Harrison were featured on a political poster countering the so-called Briggs Initiative, an anti-gay ballot measure ultimately defeated soundly by California voters. The poster showed Colvig and Harrison amidst a diverse group with the simple slogan, "Somebody in your life is gay." When Colvig boarded a bus in Watsonville and saw the poster prominently displayed, he sat down beneath it, hoping to galvanize attention to the cause. To his dismay, no one seemed to notice.

In Harrison's presence, Colvig was often quiet, electing to take a back seat even in conversations on instrument building. But this reticence could be deceptive: he was in fact intensely alert to the intellectual activity around him. Once, as Fred Lieberman and I were talking with Harrison about John Cage, we were certain Bill had drifted off. His eyes closed, chin resting on his chest, he seemed to be in another world. But as the topic turned to Cage's notorious 4'33", a piece comprised entirely of silence, Bill's head suddenly jerked up: "The second movement is my favorite part," he said, immediately resuming his former somnolent position.

We will miss you sorely, Bill, but we are comforted by the richness you have added to our lives and inspired by your stubborn, unpretentious dedication to principle.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

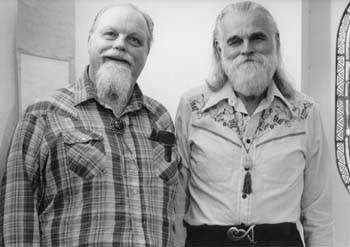

Music Makers: With a quiet passion, Bill Colvig (right, pictured with his lifelong partner of 33 years, Lou Harrison) became a visible local, statewide and national figure for his lifelong works in music, instrument-building, gay rights, ecology--and meaningful human interaction.

Leta Miller is a professor of music at UC-Santa Cruz and, with Fredric Lieberman, has just completed the book Lou Harrison: Composing a World (Oxford University Press, 1998).

From the March 8-15, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.