![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Photograph by Charlie Eckert

Twist and Shout

Forget the war on terrorism--balloon hats are the prescription for world peace

By Rebecca Patt

ADDI SOMEKH uses his intuition when he makes balloon hats for people. His improvisational process involves perceiving the person's vibe, facial features and the colors they are wearing. He imagines colors and shapes coming out of their heads.

Not long into our interview, things took an unusual twist.

From the denim apron sewn by his mother, he pulled out an assortment of balloons. With a few inhalations and twists and the addition of jiggling flourishes at the top known as dingies, Somekh fashioned a rainbow-colored crown for me made of his very breath.

He then gifted me with a jumbo-sized balloon flower and a glamorous flower-shaped ring. Wearing my crown and accessories I was grinning like a fool. I felt special, exuberant, and dignified in a goofy way. The hat brought out the real me, as if he had duplicated my aura with inflatable latex. My hair clung to the flower with static electricity, a balloon effect from childhood I had forgotten about.

My delighted reaction, I discovered, was similar to that of the Turkish school children, Norwegian soldiers, American truck drivers, African villagers in the desert and Mongols on the frozen steppe whom Somekh has made balloon hats for.

Accompanied by photographer Charlie Eckert, Somekh has traveled to 34 countries in the last few years, surprising people from all walks of life with inflatable crowns. The juxtaposition and originality of the photographs stir a fresh breeze through the mind and spirit.

"The symbolism of the headdress, combined with the positivity and the laughter, and the fact that you are making something for somebody--it's hard not to take a great photo," said Eckert.

Their expeditions led to the production of a how-to book, The Inflatable Crown (Chronicle Books), and a self-published calendar called The Varieties of the Balloon Hat Experience. Interspersed with the international photos, the how-to book reveals the mystery behind creating hat features including the dingie, swirly and instant classic, and gives step-by-step instructions for making the Ballie Brain Protector, Polar Bear Lounger and Martian Helmet, among other hats.

As soon as I saw one of Eckert's photographs, my mind was blown. I knew I had to meet these guys. I was in luck because the duo, based in New York, frequent Santa Cruz as they work on self-publishing their latest project.

Balloons for Mary

In a departure from the subject of balloon hats, the two are creating a book about art historian and former UCSC professor Mary Holmes, their friend and mentor who passed away in January at the age of 91. The book, Mary Holmes: Art and Images, is set for release this spring. It features Somekh's interviews with Holmes and Eckert's photos of her paintings and art installations.

Through Holmes' inspiration, Somekh came to understand that he is much more than a balloon twister--he is part of an ancient tradition of headdress makers.

"She was one of the first people we ever made a hat for," says Somekh, a 29-year-old from Los Altos and a 1994 UCSC grad. "When everyone said it was a far-fetched, egotistical, unrealistic, impossible idea, she said go for it."

"Hats set off the face," Holmes told Somekh. "A hat makes anybody look more dignified, more respectable. That's what crowns do, and the balloon hat is a kind of crown. And I think people feel the ancient connection in that, the dignity even with the humor, because headdresses have always elevated people."

Before engaging in hours of conversation with Holmes, Somekh had thought little about the significance of hats. Holmes' insight became even more clear to him during their travels in Africa (where they almost made it to Timbuktu, had their car not broken down on the outskirts).

"Africa was the most amazing place to make balloon hats because the headdress is so important there," Somekh says. "Before, most people thought balloon hats were fun and goofy, but in Africa it was seen as an important sign of respect to have a big, classy, colorful headdress made. When we came to a village we would have to go to the chief first and make him a hat, then his wives, then his kids, and then everyone else."

Somekh is also influenced by his love of improvisational jazz.

"Way before I became a balloon twister I wanted to be a musician," he says. "I was really blown away by how special it is to improvise and make something up on the spot."

But since he lacked musical talent, Somekh funneled his energy into hosting an improvisational jazz show at the Foothill College radio station, KFJC. He was driven to balloon twisting one summer out of "girl-related confusion" and the need to pay his car insurance. He began twisting in restaurants for tips, and he found that the activity was a good way to distract himself from his problems and put off doing his schoolwork.

"It just began to grow out of control," he said.

Photograph by Charlie Eckert

Temporary Magic

The magic of balloon hat art, Somekh says, is that it cannot be sold, hoarded or stolen. Balloon hats only last about a week, depending on conditions, but they create beauty, happiness and a shared moment that lasts far longer than the impression one typically gets from viewing art. Somekh made a balloon hat for a little girl in a village in Ghana, and when they unexpectedly passed through the village again a few weeks later, they found the little girl just sitting and clutching a deflated balloon.

Eckert, 32, says the balloon hat's beauty also involves making a unique creation, an act that's becoming rare in our industrialized society.

"You cannot underestimate the strength and the power of making something for someone," says Eckert.

Balloon hats have power as a "social accelerant," Eckert adds. In Viet Nam the pair met an anthropologist who had been unable to gain the village's trust after a year, yet within one day after making balloon hats Somekh and Eckert were drinking rice wine in the chief's hut.

"These balloon hats communicate like nothing I've ever seen before," Eckert says. "They seem to be the ultimate form of common ground."

The balloon hat experience has a way of showing how people are more similar than different. The phenomenon became most clear when they visited groups of people who had been historical enemies: Bosnians and Serbs, Palestinians and Israelis, Catholics and Protestants in Belfast.

Looking at the photographs, "we couldn't tell who was Catholic and who was Protestant," says Eckert.

Global Inflation

What began as a need for a Halloween costume turned out to be a project touching upon issues of deep social relevance.

In 1996, Somekh was in grad school in New York City and Eckert, a former art student, was designing closets in Manhattan. The two had met through mutual friends the year before. When Somekh made a couple of balloon hats for their Halloween party costumes, the headgear elicited a reaction like none Eckert had ever seen from notoriously jaded New Yorkers. They couldn't walk a block without strangers cheering and clapping at their hats.

The next day Somekh made a hungover phone call to Eckert and proposed that they travel the world taking pictures of people wearing balloon hats.

The idea "made no sense and all the sense in the world," says Eckert. They made a trial expedition to Mardi Gras, where they discovered that they worked together well.

Their first international trip was to Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. Though their families at first dismissed the idea as crazy, they were won over after watching a slide show of the trip.

After Central America, the pair made four more international trips. In-between trips, they returned to New York for a few months to work and save money. Eckert says going from regions where inhabitants wore all their clothes on their backs to building closets for Madison Avenue matrons to store their shoe collections caused him major culture shock.

Their sixth and final excursion in three years was a four-month road trip in a Volvo station wagon around America. By the end of that trip, they had gone through 100,000 balloons and taken 10,000 photographs. They returned with no money and faced an arduous task of finding a publisher. Originally they dreamed of making a coffee-table book of international photographs, but the idea was rejected. They ended up switching gears when they had the opportunity to make the how-to book.

They recently returned from Brazil, where the Discovery Channel filmed a documentary about their balloon hat work. They hope to be able to take the balloon hat experience to Australia, the only continent they have yet to visit.

Somekh aspires to make balloon hats for high-level diplomats in the middle of important negotiations.

"I would not want to do it in front of lots of photographers as a press event, but over dinner, with food and alcohol--a real party--as a way of helping them bond as friends," he says.

But his ultimate balloon-making gig would involve time travel.

"I would like to make balloon hats for real live 1960s go-go dancers at a Jimi Hendrix concert."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

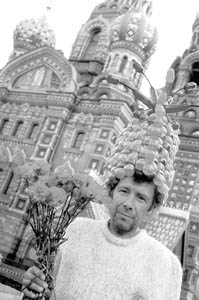

Hats Not All: A flower vendor in St. Petersburg, Russia, wears an inflatable crown that mimics the cupolas of the Hermitage Museum.

Hats Not All: A flower vendor in St. Petersburg, Russia, wears an inflatable crown that mimics the cupolas of the Hermitage Museum.

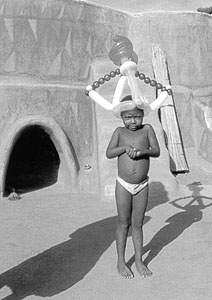

An Unusual Twist: The language of balloon hats is universal, as a little boy in Sirigu, Ghana, was delighted to learn.

An Unusual Twist: The language of balloon hats is universal, as a little boy in Sirigu, Ghana, was delighted to learn.

To learn more about Somekh and Eckert's balloon hat projects, visit www.balloonhat.com and www.maryholmesbook.com.

From the March 6-13, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.