Medical Wasteland

Robert Scheer

What should the public be more concerned about--some syringes found strewn along the coastline or the other three million-plus tons of medical waste that we may never see?

By Kelly Luker

THERE IT WAS, playing hide-and-seek with the kelp and driftwood. The used syringe was bobbing along the shoreline, just a stone's throw from the Boardwalk and the Municipal Wharf. Then another. In all, more than 130 syringes were found by beach-goers and public officials in the last week of January, a gruesome discovery that made front-page headlines.

The story didn't end there, however. More used syringes were found strewn along county beaches in the following weeks, and health officials believe a cache at Seabright Beach could be related to the Main Beach discovery.

Although some fingers point to the sloppy habits of intravenous drug users, no one's ruled out the possibility that those syringes found bobbing next to all the kiddie rides and tourist attractions might just be the result of the sloppy habits of a local doctor--maybe yours.

Those needles are merely the sharpened edge of a 3.4-million-ton iceberg known as medical waste, a major headache in this country for communities, regulators and those who must figure out how to dispose of the messy trail left behind by humans--or their pets--when those paths cross with that of the health-care industry.

It was a similar flotilla of syringes docking on the New Jersey shore in the late 1980s that first prompted a federal response to what was perceived as slipshod handling of medical waste.

The Federal Medical Waste Tracking Act of 1988 was a two-year experiment to determine if medical waste should be regulated separately from other refuse. Although the feds did not want to handle the regulation directly, they urged states to pick up the baton. By 1997, two-thirds of the states--including California--had instituted some regulatory guidelines for medical-waste "generators." The term encompasses a vast array of services that includes not only doctors and dentists but also animal hospitals, funeral homes, pathology laboratories and nursing facilities.

Pondering what is left over when the doctors, coroners and others have done their jobs--well or poorly--invites a deep meditation on the vestiges of the human body that most of us would rather not consider. Acres of bloody, pus-drenched bandages. Tons of urine- and feces-soaked pads. Miles of plastic tubing used to transport stomach and bowel contents. Amputated limbs, expunged cancers, liposuctioned fat, aborted fetuses. All, by law, must find a final graveyard that guarantees no chance of infection to those still living.

The path to that final resting place can be expensive, not only in money but also in time, training, paperwork and related overhead. Following the adage that one man's trash is another man's treasure, a tidy little industry--make that a tidy big industry--has sprung up in the wake of this odiferous wave.

Mike Malloy, senior editor of the trade publication Waste Age, figures that those syringes bouncing along the Jersey shore a decade ago have spawned an industry worth close to a billion dollars today, which each year nabs an increasing chunk of health-care providers' operating budgets.

One example is VCA Animal Hospital of Santa Cruz, which is part of a 160-clinic chain located throughout the country. Reached at corporate headquarters in Santa Monica, Steven May, vice-president of corporate marketing, says that medical-waste containment, education and disposal cost the chain between $6 and $7 million a year.

"It's a serious expense," May admits.

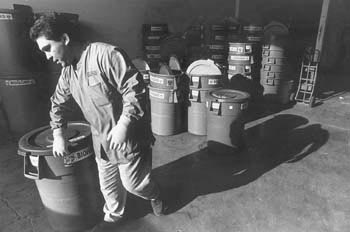

Haul of Fame: Rick Alaniz, operations manager for Monterey Bay Medical Waste, hauls empty waste containers out to his van in preparation for morning collection in Monterey.

Talking Trash

SO, HOW DOES one keep track of a few million tons of medical waste a year? Michael Schott will be happy to tell you. An environmental specialist for the Medical Waste Management Program for the State Department of Health Services in Sacramento, Schott is a walking compendium of government code sections relating to the misunderstood world of bloody bandages and throwaway bedpans.

He is also living proof that anyone--anyone--can love his job. Like a traveling preacher with his Good Book, Schott can gleefully quote sections of California medical waste regulations, chapter and verse.

I slow pitch him an easy one--what, exactly, is a medical-waste generator?

"Go to Section 117705," directs Schott, "where it says, 'Medical-waste generator' means any person whose act or process produces medical waste and includes, but is not limited to, a provider of health care, as defined in subdivision (d) of Section 56.05 of the Civil Code.' "

OK, so how does the state define various types of medical waste and what happens to them? Schott offers up the euphemistic "tissues" as an example: "Go to Section 118220," he says and begins quoting from memory: "Recognizable human anatomical parts, with the exception of teeth not deemed infectious by the attending physician and surgeon or dentist, shall be disposed of by interment ..."

As he continues, I gaze down at the drumstick I've been gnawing on for lunch while we conduct the interview and bid a fond farewell to my appetite. Schott, however, chugs right along.

Businesses are regulated according to the amount of medical waste they generate. Large Quantity Generators (LQG)--creating more than 200 pounds a month--are inspected at least once a year, as are Small Quantity Generators (SQG), those that produce fewer than 200 pounds but more than 20 pounds a month.

However, the great majority of medical practices fall in the nether-world category of "registered" generators, those that produce fewer than 20 pounds of medical waste a month. Such businesses pay a small fee to register with the enforcing agency--state or county--but legally do not have to be inspected.

Smaller counties in California, such as San Benito, have elected to allow the state to enforce the medical waste code. In both Santa Cruz and Monterey counties, however, county officials inspect the medical-waste generators, and Schott directs me to the Santa Cruz County Department of Environmental Health.

Hazardous-materials program manager Steven Schneider says that in the county there are about 50 LQGs and SQGs combined, but there are more than five times that number--273 businesses or practitioners--that fall in the "registered" category that requires no inspection.

Although most small businesses use medical-waste haulers, some may choose to use alternative medical waste treatments. They can, for instance, mail in "sharps," a subset of medical waste that includes needles and scalpels, to a disposal facility. Schott says the mail process is strictly regulated by the United States Post Office.

Businesses may also do on-site autoclave treatment, which sterilizes waste with a high-pressure steam process, or use an isolyser--a gel-compound treatment that renders sharps sterile. Schneider says that although it is not required to do so, his office inspects a third of the "registered" generators each year, just to take "a proactive stance."

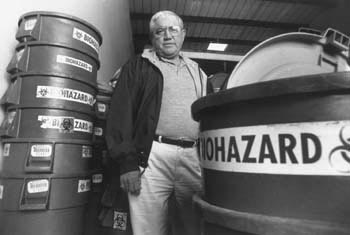

Hazarding a Guess: Abe Vargas knows that defining medical waste is an interpretive art under the best of circumstances.

Primary Colors

'I KNOW THERE'S places that aren't complying [with the regulations]," says Abe Vargas. Vargas owns Monterey Bay Medical Waste, one of a handful of medical-waste haulers for Santa Cruz, San Benito and Monterey counties.

When Vargas began the business seven years ago, after California drafted its set of medical-waste regulations, he recalls going through the tricounty area's phone books and compiling a list of about 1,300 potential clients. Seven years later, he has a few more than 700 of those accounts. Vargas subcontracts to Browning-Ferris Industries Inc. (BFI), one of the largest waste haulers in the country, which also handles several of the larger accounts in the area.

"It could be a possibility that someone would do that to save money," figures Vargas, when asked his ideas about the syringes found dumped on the beach.

However, the hauler leans toward the theory that those syringes fell under the category of "home-generated" medical waste, the unregulated detritus of diabetics and junkies. Although little can be done about illicitly generated medical waste, the hazard created by some diabetics and other legitimate users of needles has warranted concern. Sometimes those needles end up in a landfill or, worse, are flushed down the toilet. In response, Vargas reports that he is working with officials from the three counties to obtain a grant to educate diabetics and supply them with recyclable sharps containers.

Vargas has done well in this business. Although he is meeting with me today outside Dominican Hospital's radiology clinic to demonstrate a typical medical waste pickup, Vargas admits he's a bit rusty. A driver handles most of the pickups these days, allowing Vargas to do paperwork and spend a fair amount of time doing what he loves best--a few rounds on the golf course.

Donning heavy rubber gloves, Vargas grabs an empty barrel labeled "infectious waste" out of his truck and heads upstairs to the clinic. As he reaches into the clinic's closet and exchanges a full barrel for the empty one, Vargas explains about color-coding. Gray bags are used for infectious waste (bandages, wrappings, tubings), yellow bags hold trace chemotherapy waste and red bags are for what is delicately termed "tissues." Red plastic jugs and boxes are used to dispose of sharps.

Although the sight of syringes tossing about the surf or hiding in the park playground brings the most outrage from communities, it is, surprisingly, the easiest and least expensive waste for medical facilities to handle, says Vargas. A small office may only pay $20 to $40 every few months for pickup of a sharps container.

Because sharps are so inexpensive to dispose of, the discovery of hundreds of multisized needles (diabetics use only one size) only adds to the mystery of the Main Beach cache.

The day's haul is taken back to Vargas' warehouse in Salinas, then picked up by BFI and hauled to Fresno. BFI will either autoclave or microwave some of the waste to ready it for a landfill and will ship the remainder out of state for incineration. (The only off-site medical incinerators in California are owned by BFI's competitors.)

Until 1990, most medical waste in this country was burned in one of about 2,400 medical-waste incinerators scattered throughout 42 states. California had 146 medical-waste incinerators. Since medical waste regulations were enacted at the beginning of this decade, that number has dropped to fewer than a dozen statewide.

Although tissues and trace chemotherapy waste are invariably incinerated, garbage labeled "infectious waste" (which accounts for about half a million tons, or one-seventh of the country's yearly output of medical waste) may also be burned. Although a more expensive process, it may also be sterilized through autoclave or microwave technology, then sent to a landfill.

TRYING TO COMPARE the county's list of medical waste generators with a current phone book of practitioners in order to see if the numbers match up quickly becomes, in Schott's words, an "opus magnus."

Clinics can include dozens of doctors, dentists or veterinarians, each listed separately. In the highly conglomerated world of health care, confusion reigns as to what or who is inspected: the clinic site, the individual medical practitioner or the corporate entity. Sometimes all three are listed in the Santa Cruz database of generators, each with a different code.

Most interesting, perhaps, are some of the health-care services merely "registered" with the county--the vast majority considered to generate "very small" quantities of medical waste and therefore subject to less regulation and inspection.

Vargas looks at the list and shakes his head when he sees some of the companies classified as "very small" medical waste generators. "Oh, I can't imagine that," he laughs. However, creating fewer than 20 pounds a month of medical waste for a large clinic might not be that difficult because of the hazy definition of medical waste.

In search of some clarity, I check back with Schott in Sacramento. He begins to reel off yet another code number--"Section 25117.5 of the old Health and Safety Code defined infectious as ..."--before I stop him and ask for the big picture.

Schott explains that, indeed, there is a fair amount of personal interpretation involved in defining infectious waste, now known officially as biohazard waste. What is a blood-specked bandage, which hits the regular trash, as opposed to blood-soaked bandaging, which is required to be counted as infectious waste?

This open interpretation has contributed to a situation in which the majority of medical-waste generators fall under the least amount of scrutiny. Which leads back to the syringes on the beach. "There could be hundreds [of businesses] that threw that stuff on the beach--exactly," Schott confirms.

The reason that most health-care businesses slip through regulatory nets is historical, explains the waste expert. While the original legislation had a provision to register and equally regulate every waste generator in the state, industry lobbyists proved too powerful.

"That explains the division among 'large,' 'small' and 'other,' " Schott says. "The medical, dental and veterinary associations just said no and had the political clout to back it [up]."

Schneider, however, is convinced that the businesses do a good job at policing themselves. "Most of them are concerned with protecting their professional reputation," he says. "There is a medical community, and if they were doing something wrong, word would get out and affect their reputation."

Schneider can count only a handful of violations in the past seven years, most stemming from miseducation rather than efforts to beat the system.

Hauler Vargas, however, tells of a few troubling situations that the local inspectors never got wind of. He recalls getting a phone call once from a receptionist who recently began work at a local medical office--Vargas will not say which one. When he arrived, he discovered bags of medical waste that had been accumulating in the clinic's basement for 15 years. Vargas hauled it away, and county officials were none the wiser.

Vargas does give the inspectors high marks for how they do their work. He's gotten calls from the department when things don't look quite right to an inspector. And although medical-waste regulations have provided Vargas his livelihood, he doesn't think they need to be any more stringent than they are.

Schneider believes that oversight is working well in this area. "We do find syringes occasionally along the beach--I can't explain why," Schneider says.

But, he adds, "I feel pretty confident that medical waste is well regulated here."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Roll Out the Barrels: Abe Vargas, owner of Monterey Bay Medical Waste, stands in his Salinas facility, where medical waste from three counties is collected.

Roll Out the Barrels: Abe Vargas, owner of Monterey Bay Medical Waste, stands in his Salinas facility, where medical waste from three counties is collected.

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

From the March 5-11, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)