![[Metroactive Stage]](/stage/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

'Merchant' of Menace

Gareth Armstrong delves into the controversy around Shakespeare's most hot-button creation in 'Shylock'

By Mike Connor

There is no force in the decrees of Venice.

I stand for judgement.

--Shylock, from Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice

Truth be told, most of us could easily afford to lose a pound of flesh these days, flabby hippos that we are. But not even Hollywood's finest would want it hacked haphazardly from their bodies. They want precision: a nip here, a tuck there, and plenty of general anaesthetic. Enter knife-toting lunatic ready to carve gaping hunk out of Hollywood starlet; exit Hollywood starlet in flurry of screams and jiggling cellulite. Close curtain on entire disturbing scene.

Rewind back to Elizabethan times, when Shakespeare was writing what would become one of his most controversial plays, The Merchant of Venice, in which he paints an unflattering portrait of a Jewish moneylender called Shylock. Such a villainous character is this Shylock that he demands a pound of the gentile Antonio's flesh as payment for a delinquent debt. Even when Antonio's friends offer to pay twice the amount owed, Shylock remains vengefully unmoved, yammering on about laws and judgments, sharpening his knife.

Back in those days, Jews were the redheaded stepchild of the theater; actors playing Jews would don a curly red wig and a huge hooked nose to add to the buffoonery. Shylock, for all his treachery, was the farcical character in a romantic comedy. Fast-forward to the present, when centuries of interpretations and criticisms of Shylock (not to mention centuries of Jewish persecution) stand between the writer and present-day audiences. Some people take such offence to Shakespeare's apparent anti-Semitism that they object to the play being performed at all. The Merchant of Venice was, after all, one of Hitler's favorite plays ... once the Nazis had devised a "solution" to a minor Jewish problem in the plot.

Welsh writer and Royal Shakespeare Company alum Gareth Armstrong runs head-first into the bubbling cauldron of controversy with his one-man play, Shylock. In it, he puts Shakespeare and his character Shylock into historical context, exploring the roots (and many of the horrifying consequences) of anti-Semitism. It's a sobering look at a history of persecution, but it's also a wonderful piece of theater: enjoyable, intelligent, painstakingly researched and, thanks to a brilliant stroke of narrative genius, often pretty durn funny.

Tubal Ligation

Armstrong is downright charming as the irrepressible Tubal, a character with only eight lines in one scene of The Merchant of Venice. "But it's a great scene!" shouts Armstrong as Tubal, chock-full of cheery bravado. Humble and upbeat in the face of centuries of persecution, Armstrong's Tubal is, of course, biased, but still allows the audience to judge for themselves the crimes he relates.

And so it goes, with Tubal as your faithful guide through the creation of The Merchant of Venice (Shakespeare pinched the plot and character from the 14th-century Italian fairy tale Il Pecorone) to the evolution of the various productions over the centuries. It's been cut down and beefed up; it's been censored (or bowdlerized, as it were), banned and celebrated over the years. He discusses Shakespearean innovators, actors like Edmund Kean and Henry Irving who were determined to reinvent Shylock as a character more tragic than tyrannical.

Despite Armstrong's gentile status (he's the son of a Presbyterian minister and a self-professed lapsed Christian), he did his homework and dug up a slew of historical anecdotes and plenty of the skeletons of anti-Semitism, which he sews seamlessly into the body of the play. He ties the image of the blood-sucking vampire to the so-called blood libel in England, wherein vicious slanders about Jews kidnapping children and using their blood to make matzo became "the excuse for the wholesale massacre of the Jews."

"After I'd been playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, I was really intrigued by the character," says Armstrong. "I did a lot of research, and at the end of the run I decided I'd do something with it. Being an actor, of course, you make it into a theater piece."

"I was exercising in the gym, thinking, 'Who am I going to make the conduit?'" Armstrong continues. "I knew It couldn't be Shylock--he's such a stark character, and I knew the audience wouldn't want to spend an evening being spoken at. Tubal was an everyman character, he could represent all Jewish people, all small actors, all Shakespeare worshippers. [He offered] a chance to lighten the story up, because he can be a comic storyteller."

If you haven't seen or read The Merchant of Venice, rest assured. Armstrong does a thorough job of explaining the plot, and even goes to the trouble to act out some of the relevant scenes from the play, deftly switching from character to character.

Armstrong manages to make a convincing argument that Shakespeare's Shylock is more relevant now than ever. He focuses on the pieces of text that describe a man victimized, making the point that this bitter old moneylender is more than just a necessary evil to give a play some conflict. In one of his more lucid moments, Shylock himself spells out the absurdity of the prejudice against him: "I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is?"

Armstrong connects the dots between Shylock's keen sense of injustice and his bitter, vengeful spirit, which we see spiral down into uncompromising villainy and even cause him to transgress his own religious beliefs.

"The play is ostensibly comic romance," Armstrong explains, "but the play has been hijacked by Shylock, I suspect, since it was first performed. For many years they used to cut the last act after Shylock makes his exit; there is no doubt that Shylock is the central figure. Even if that's not what Shakespeare intended, that's the way it plays."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Buy Shakespeare's script for 'The Merchant of Venice'.

![]()

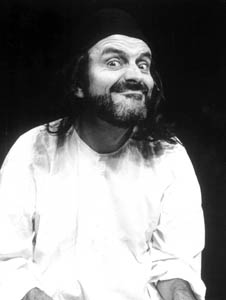

Trouble in Mime: Keep an eye on this Gareth Armstrong guy. He looks like he might start walking on the wind at any moment.

The pound of flesh, which I demand of him,

Is dearly bought, 'tis mine

and I will have it.

If you deny me, fie upon

your law!

Answer--shall I have it?

Shylock plays March 7 and 8 at 8pm at the UCSC Theater Arts Mainstage. Tickets are $23 general admission, $19 students and seniors w/ ID, $11 UCSC students w/ ID. Call the UCSC ticket office at 831.459.22159, or visit the Arts & Lectures website at http://events.ucsc.edu/artslecs/.

From the March 5-12, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.