![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Portraits of The Past

Two image collections resurrect forgotten heroes of the camera

By Geoffrey Dunn

Dassonville: William E. Dassonville, California Photographer

AT A TIME when the Museum of Modern Art in New York is relying on the familiar in its current photographic homage to Walker Evans, a pair of small West Coast publishers has produced magnificent collections of photographs by largely unknown artists of the same era that are far more vital and challenging than the standard fair offered up this spring by MOMA.

Both First Son: Portraits by C.D. Hoy and Dassonville: William E. Dassonville, California Photographer provide rare glimpses into worlds that have long since vanished. Both are brilliantly designed and intelligently composed, with thoughtful commentary that frames their subjects--and their respective oeuvres--in proper historic and artistic contexts.

Chow Dong Hoy was born in the impoverished Guangdong province of China in 1883, the ninth child--and culturally significant first son--in a brood of a dozen children. He was briefly educated in his home village, then sent off to earn his own way at the age of 12.

Hoy immigrated to Canada in 1902. Landing in Vancouver, he took various employment as a houseboy, dishwasher, cook, fur trader, ax man and surveyor, with each step slowly working his way into British Columbia's rough-and-tumble Cariboo region. In 1909, he set up shop as a portrait photographer in the mining town of Quesnel, and then moved two years later to the larger, multicultural community of Barkerville, where he supplemented his photography income with work as a watch repairman and barber.

Hoy's 96 portraits collected in First Son represent the most stunning assemblage of photographs I've encountered since the publication of Sebastiao Salgado's Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age in 1993. We see First Nation people (native Canadians) mixed with Chinese immigrants mixed with Canadians of European descent. They are, for the most part, portrayed in an intimate, egalitarian manner--an equality born of Canada's unforgiving interior.

The individuals in these photos reflect a dignity and human spirit absent from most ethnographic photography. Nor are these subjects idealized in the "noble savage" tradition of Edward Curtis.

As Faith Moosang notes in her superb companion essay to the photographs, "The frank, open look on the people's faces in Hoy's portraits, and the lack of romanticism in the setting and light effects, reveal the difference between being photographed for someone else's story and being photographed for your own. ... They are friends, families, lovers and individuals."

One of the defining aspects of Hoy's work is his foregrounding of his subjects' hands, providing a common point of entry into each of their lives. One of my favorite Hoy portraits is of "Mathilda Joe," a First Nation woman known for her hunting skills. In Hoy's composition, her left hand is placed jauntily on her hip, while all we see of her right hand is a strong, thick thumb, braced against a chair. Her thumb is a defining element of the portrait.

AS DID C.D. HOY, William Dassonville made his living as a portrait photographer, and although born within four years of each other, their lives--and their artistic careers--were as disparate as the communities in which they lived and worked.

Born to middle-class parents in Sacramento in 1879, Dassonville moved to San Francisco in his youth, where he attended the upscale Trinity School, a private academy for boys. He was given a camera and used it to photograph friends and relatives, as well as to chronicle his frequent journeys into the Sierra Nevada.

During his early 20s, he joined San Francisco's avant-garde Camera Club and became well-acquainted with bohemian artists in the city, including William Keith, George Stirling and Maynard Dixon, all of whom he photographed in formal portraits. He supported himself with his portraits, and later invented a popular developing paper known as "Charcoal Black."

Although he achieved considerable acclaim as a photographer in his early life, both Dassonville's business dealings and family life went sour, and he finished up his life as a relatively isolated medical photographer at Stanford University. It was only when art dealers Susan Herzig and Paul Hetzmann discovered his photos in a pair of trunks three years ago that his reputation as a photographer was restored.

Dassonville's photographs echoed the late-19th-century tonalist movement in painting in both their muted, impressionistic imagery as well as their reverence for the vanishing landscape. His portraits were equally impressionistic. To my mind, his images of the Yosemite Valley, for instance, supersede those of more-celebrated photographers such as Ansel Adams in both expression and composition. They are haunting poems of landscape imagery.

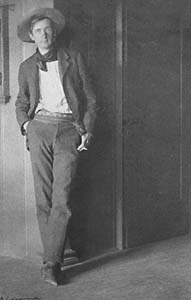

Dassonville's portraits are equally haunting. His full-bodied photo of the celebrated artist Maynard Dixon, ironically, shares many of the qualities of Hoy's portrait of Mathilda Joe. Dixon's right hand is thrust into his pants pocket, while his left hand assuredly holds a cigarette. The artist's quiet confidence exudes from the imagery.

"In portrait photography, there are two individualities to be considered--the photographer's and that of the person being photographed," Dassonville wrote in his early career. "Both should be considered, but this is too seldom the case with some workers who have individualized themselves and whose work is so strongly stamped with their own individuality as to entirely obliterate that of the person being photographed."

Neither Dassonville's nor Hoy's portraits obliterated the individuality of their subjects. If anything, they intensified it. Indeed, there is a combined balance in their works that sets a noble standard for photographic construction.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Mathilda Joe: A portrait from C.D. Hoy's 'First Son'

Mathilda Joe: A portrait from C.D. Hoy's 'First Son'

First Son: Portraits by C.D. Hoy

By Faith Moosang

Presentation House Gallery/Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver; 160 pages; $27.95 paper

Essay by Peter Palmquist

Carl Mautz Publishing, Nevada; 109 pages; $35 paper

Maynard Dixon: A portrait of the Western artist by William E. Dassonville

Maynard Dixon: A portrait of the Western artist by William E. Dassonville

From the March 1-8, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.