![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Wage Warriors

Dozens of cities, including San Jose and Oakland, have one. Now labor and community activists here say it's time for a living-wage law in Santa Cruz, too.

By John Yewell

SANTA CRUZ IS BEING loved to death. Anecdotally speaking, the monthly cost of living exceeds the average annual income for many Third World countries. But the evidence goes beyond anecdote. Santa Cruz ranks seventh nationally in the percentage of the minimum wage needed to afford a two-bedroom home (356 percent) and seventh in the number of hours needed to work each week to pay for it (142).

Such brutal numbers should give pause even to the most upbeat IPO millionaire. Numbers like those have also given impetus to an issue sweeping the country, coming soon to a city council near you: the living wage.

For months, representatives of the Community Action Board of Santa Cruz County, the Service Employees International Union Local 415 (the union that represents city and county workers) and other groups have met as the Coalition for a Living Wage to gather information and to hammer out a living-wage proposal to present to the Santa Cruz City Council.

The plan's keystone will be an hourly wage of $14 ($13 if benefits are included) for employees of certain firms that contract with the city and, eventually, for all city employees. The wage would not supersede existing union contracts and would apply only to firms that receive more than $25,000 in development assistance or win city contracts above $5,000 or $10,000 (the coalition hasn't yet decided which level it will propose).

The campaign will parallel the city's spring budget deliberations, aiming for passage by July 1. A kickoff event March 16 will attempt to galvanize progressive supporters to overcome anticipated objections from the business community. After setbacks on the issues of widening Highway 1 and the downtown Borders store, many progressives feel they could use a win.

Living (Wage) in the Past

A RISING TIDE, the old economics adage goes, lifts all boats, but lately the poor have been getting swamped. Despite the current, record-breaking economic boom, a recent spate of news reports supports claims of a growing gap between the rich and poor, encouraging the sentiment that working people should share more of the bounty--or at least earn enough from their labors to live decent lives without public assistance.

This is easier said than done, although in some small ways it is already done. The institution of the minimum wage in 1938 (it started at 25 cents an hour) was supposed to help people out of poverty, but its buying power has been sapped by years of wage stagnation.

In 1931, Congress passed the Davis-Bacon Act (named for the two Republican congressmen who introduced it) instituting what's known as the "prevailing wage." The act requires contractors doing business with the federal government to pay their workers at the same rate as the majority of workers in a given industry performing the same tasks. Davis-Bacon effectively makes union wages industry standards, and most states have similar laws.

The idea of a living wage is the latest tool to encourage the redistribution of wealth--that old bugaboo that offends the Cato Institute, Ayn Randinistas and other class warriors on the right. The battle has already been fought with varying success in dozens of cities around the country. Baltimore in 1994 was the first to pass such a law. It started at the hourly rate of $6.10 (it's now $7.90) and applies only to city service contractors and their subcontractors.

WOW

LOCALLY, DISCUSSION of a living-wage law has been under way for some time. Two years ago, the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors asked its Human Resources Agency to produce a report addressing the problem of limited livable-wage opportunities in the county.

The report, issued last June, defines a living wage as "the level of income necessary for a given family type to become independent of welfare or other public and/or private subsidies." Its conclusions rely on data derived from a 1996 report called the "Self-Sufficiency Standard for California," produced by Wider Opportunities for Women, a Washington, D.C., organization. The WOW study concluded that the hourly wage necessary for a single parent with two children (one preschooler and one school age) to live independently in Santa Cruz County was $17.21.

Factoring in housing, transportation, taxes, child and medical care, food and miscellaneous expenses, Wider Opportunities for Women produced numbers for no fewer than 70 categories of family circumstances, varying by number of parents and ages of children. The results ranged from a low of $5.11 (the federal minimum wage is $5.10) an hour per person for two working adults with no kids, up to $29.72 an hour for a single parent with three infants.

Deciding what type of household constitutes the fairest basis for determining a living wage that must apply across the employee spectrum is a conundrum, thanks principally to major differences in the costs of housing and child care.

Still, the Coalition for a Living Wage had to choose, so it settled on a recommendation of $14 an hour. This figure stems from the family model of a single adult with one preschooler, which, according to the four-year-old WOW study, would require a $14.01 hourly wage--or a salary of roughly $29,000 per year.

In San Jose, the same family model would require a wage of $14.24, showing how similar the costs of living between the two areas are. The WOW study, which measured costs independently by county, was also the basis for a study produced by Santa Clara County before San Jose passed its Living Wage ordinance in November 1998.

Bridging the Wage Gap: Santa Cruz resident Laura Tucker, with her 2-year-old son Gabriel, is a temporary city worker who currently makes $8 an hour and would benefit from a living-wage law.

Models of Behavior

THE INITIAL PROPOSAL BY Working Partnerships, which promoted the San Jose living-wage ordinance, asked for a $12.50 wage, which was based on a slightly different family model than the one under consideration in Santa Cruz--that of one adult and one school-age child. In the end, the San Jose City Council opted for a $9.50-per-hour wage for companies subject to the law that provide health and other benefits, and $10.75 for those that don't.

Amy Dean, Working Partnerships' founding director, says the $9.50 and $10.75 figures were derived using a formula that starts with the federal poverty level and takes into account cost-of-living factors. The problem, Dean says, is that the federal poverty level and minimum wage have not kept up with the true cost of living.

Though it didn't get the wage it wanted, Working Partnerships did push successfully for elements in the San Jose ordinance to strengthen worker protections. These elements can be found in similar form in ordinances adopted by other cities:

In addition, unionized city workers whose hourly wage was less than $9.50 at the time of passage of the San Jose living-wage law were all brought up to that level when the next contract was negotiated.

The proposal put forward by the Coalition for a Living Wage in Santa Cruz will include those elements in some form along with a few others:

What's Good for the Goose

IF LIVING-WAGE LAWS have one thing in common, it is that they vary widely depending on local political and economic factors. Comparing apples to oranges is difficult. Few studies exist on the impact of living-wage ordinances on cities, taxpayers or on contracting firms and their employees. Two studies of a proposed San Francisco living-wage law (for $11 an hour) came to diverging conclusions.

Due to the lack of data, the battle over a living-wage ordinance in Santa Cruz is likely to be fought with crude weapons. But two studies of the Baltimore lawshowed that the cost of city contracts did not increase. The studies also claim that staffing levels were not reduced and that employers reported satisfaction with how the law leveled the playing field by relieving pressure on labor costs.

Proponents also point to a study of the Los Angeles living-wage law by Professor Robert Pollin of UC-Riverside. The study claims a 50-percent reduction in government subsidies to workers affected by the law--without increased unemployment.

The Santa Cruz Coalition for a Living Wage touts these studies and backs up the need for the law with familiar statistics about the difficulties average people in the county have making ends meet. And the coalition argues that if businesses such as the Gateway Development and the Cooper House in the future expect to qualify for city financial assistance (Gateway got $675,000 in assistance; the Cooper House got $1 million), then they should expect to pass some portion of those benefits on to project workers. The wage would not have to apply to businesses who later occupy the project.

Coalition for a Living Wage spokesperson Nora Hochman estimates that some 300 workers for nonprofits and social-services providers with city contracts above the financial threshold amount and more than 500 temporary city workers could be affected. In addition, 108 SEIU members who currently make less than $14 an hour could see their pay increased during the next round of contract negotiations.

There are no figures available on how much that might add to the city budget--or on the potential impact on labor costs for city contractors. But a study of the impact of the first year of the San Jose law is under way and will likely be completed in time to inform the debate over a Santa Cruz law.

More than two dozen cities have some form of living-wage law, including Oakland, Chicago, Boston, Minneapolis/St. Paul and Detroit, as well as smaller cities like Pasadena, Duluth, Minn., and Somerville, Mass. Even though their hourly rates differ, adjusted for the cost of living, many are similar to the $14 proposed for Santa Cruz. Using U.S. Census statistical information, the coalition estimates that Baltimore's $7.90 would be worth $13.77 when adjusted for Santa Cruz's cost of living; Des Moines' $7 becomes $12.68; St. Paul's $8.47 becomes $14.96.

Choose Your Weapons

THERE IS OPPOSITION. Nationally, it is led by the fast-food industry-funded Employment Policies Institute--to be distinguished from the Economics Policy Institute, a liberal think tank. Locally, the Chamber of Commerce is expected to raise objections.

A year ago, Michael Schmidt, executive director of the chamber, told a local reporter in the context of a question about a living wage that an $8-an-hour minimum wage would hurt local businesses that depend on tourism.

"You might as well shut the puppy down," he said in a Sentinel article published Feb. 14, 1999. "You're just going to kill the industry."

Of course, the current proposal would not apply to private business in non-city contract dealings, but supporters do see it as a benchmark with potentially broader applications in the local business community. And there are plans eventually to present the proposal to the Board of Supervisors for adoption at the county level, where the economic impact would be much greater.

More recently, Schmidt told Metro Santa Cruz that an informal chamber study suggests that a $15,000 annual salary was "livable." That figure works out to about $7.21 an hour, 54 cents above the federal poverty guideline for a family of three, according to the nonprofit California Budget Project.

The County Human Resources Agency estimates an hourly wage of $7.27 to be the average placement wage for CalWorks parents (the state's welfare-to-work plan), but the same study says that 40 percent of the CalWorks population are not earning enough to go off cash aid. Based on the county's definition of a living wage--achieving independence from taxpayer-supported subsidies--some suggest a salary at that level amounts to a public subsidy of private-industry wages.

The example of San Jose, on the other hand, cuts two ways--presenting a working example of the law in similar economic circumstances, yet undercutting the appeal for a wage rate as high as $14. There are also problems for supporters themselves, who tend not to practice what they preach.

Coalition for a Livable Wage coordinator Sandy Brown admits that the Community Action Board currently does not pay all its employees the living wage being advocated by the coalition. But she says the CAB, which is the fiscal agent for the coalition, is reviewing its policies and plans to bring wages in line with living wage levels.

The main national promoter of a livable wage, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), has no policy to honor living-wage laws voluntarily in the cities where it operates--and is notorious for paying low wages to its employees.

Still, the living wage is an idea with obvious local appeal and a city council philosophically inclined to support it.

Vice Mayor Tim Fitzmaurice is likely to be the council member most actively pushing the proposal. He says he hasn't discussed it with the business community or even his fellow council members yet, but he's optimistic.

"It's something I see coming, and I want to be ahead of it," Fitzmaurice says. "My personal indication to people has been that I'm interested in the issue. My fundamental goal is to preserve communities. We're trying to be responsible."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

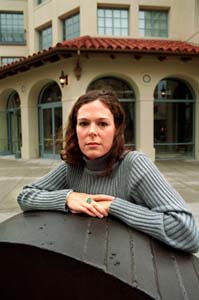

Balancing the Wage Scales: Standing in front of the Cooper House, which received a $1 million subsidy from the City of Santa Cruz Redevelopment Agency, Coalition for a Living Wage coordinator Sandy Brown thinks it's time some of that money went into the pockets of working people.

Balancing the Wage Scales: Standing in front of the Cooper House, which received a $1 million subsidy from the City of Santa Cruz Redevelopment Agency, Coalition for a Living Wage coordinator Sandy Brown thinks it's time some of that money went into the pockets of working people.

Photograph by George Sakkestad

From the February 16-23, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.