![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Making Sense

Is David Byrne, the thinking person's rock star, actually becoming accessible?

By Alan Sculley

IN THE COURSE OF RECORDING his 2001 release, Look Into the Eyeball, David Byrne realized that he had written some of the most melodic and accessible music of his career. It was a thought that unnerved the multitalented songwriter, performer, filmmaker and artist.

"I have a little bit of that prejudice that I think a lot of us have," Byrne says. "That if something sounds too easy on the ears, if it sounds kind of pretty or beautiful, your first assumption is that it doesn't have much depth to it, or it doesn't have anything radical or important to say.

"I think it's an erroneous assumption," he continues. "But it's one that's there. And I tie that over into when I hear my own stuff. If something sounds real pretty, I think, 'Oh, that's not very good.' But I think it's a false assumption to [dismiss things] that way."

The need to challenge himself musically has been an ongoing thread throughout Byrne's career, be it with the Talking Heads, the innovative, multifaceted group he co-founded in 1975, or since leaving that band in the late '80s to concentrate on his solo career. Over the course of eight studio albums, the Talking Heads' music evolved from spare, angular pop into a full-bodied, groove-oriented sound that drew strongly on African and other world-beat rhythms without losing the pop sense that had always been a major facet of the band.

In fact, Byrne's decision to leave the Talking Heads was partly the result of realizing that he couldn't pursue some of his musical ambitions within the context of the group.

At the time, the Talking Heads had released their final studio CD, Naked, and Byrne had turned his attention toward his ever-growing interest in world-beat music. He wanted to release a Latin-flavored album, an idea that didn't fly with the three other members of the Talking Heads, guitarist Jerry Harrison, bassist Tina Weymouth and drummer Chris Frantz.

"I wanted to do a Latin record, and, well, I took some of the songs to Talking Heads, but they didn't want to do them," Byrne said. "That didn't leave me too many choices."

Of course there were other issues, one of which was the tension resulting from Byrne's growing prominence as the Heads' focal point during the latter stages of the band's tenure.

By the mid '80s, Byrne had branched out into a variety of outside projects. Working with producer Brian Eno, he had explored African music on 1981's My Life in the Bush Of Ghosts. He had directed the 1986 movie True Stories. He had also collaborated with Robert Wilson on the theatrical production The Knee Plays and with noted choreographer Twyla Tharp on the Broadway production of The Catherine Wheel.

Amid such projects, the New York Times Magazine did a cover story on Byrne, proclaiming him the "thinking man's rock star." He was also featured on the cover of Time magazine, which called Byrne "rock's renaissance man."

It was clear that the other members of the Talking Heads resented the assumption that Byrne was the creative engine behind the group. In some circles, it was suggested that Byrne had essentially taken over the Talking Heads.

"They're right about part of that," Byrne says when asked about the situation. "I don't know about taking over [the band]. I don't think that part happened. But the press was definitely focusing on me, which I think was not a good thing. Yeah, it was very divisive, and of course a lot of the press liked that, too."

Though the Talking Heads never officially announced a breakup, by 1989 the group had essentially split. "It wasn't fun when I left, and it hadn't been fun for awhile," Byrne says. "I think we were still making good music, so I think that part worked out OK. But I thought, 'This is not what this is about. I'm not into being a martyr here.'"

So Byrne stepped into the next phase of his career with both feet. He founded a record label, Luaka Bop, that focused largely on showcasing the music of South America and Africa.

As a solo artist, he continued to delve further into various combinations of world beat and pop. First out was his 1989 album of Latin music, Rei Momo. The set drew mixed reviews, however, and Byrne received a healthy amount of criticism from musicians and writers who felt his music lacked authenticity.

Byrne's restless spirit, though, was not deterred, and he continued to draw from an eclectic range of musical influences in the solo albums that followed.

Uh-Oh highlighted more of Byrne's pop tendencies and is the solo album most similar to Look Into the Eyeball. David Byrne, released in 1994, found him shifting his music into a leaner, more intimate setting, while 1997's Feelings went more eclectic as Byrne collaborated with artists ranging from the Colombian music producer Joe Galdo to the new wave art-rock band Devo.

For Look Into the Eyeball, Byrne entered into the project with a general concept he wanted to pursue.

"The self-titled album pretty much had a simple concept that I would put together a band, a real band, take it on the road and then record after we played a bunch of live dates, which we did," Byrne said. "The Feelings record, though, was a bit all over the place. The only concept I can think of there was the fact that it was a collaboration with a lot of people. This one was, yeah, more musically defined--bass and drums, some percussion and strings. And pretty much that was the musical palette on most of the songs."

Working within that format, which Byrne has extended on tour by featuring a six-piece string section in his current band, pushed Byrne's music into a more melodic direction.

On the new album, Byrne is especially successful at merging percolating rhythms with soaring string and vocal melodies in the song "The Great Intoxication." "Desconocido Soy," sung entirely in Spanish, shifts the focus more to a grooving beat without losing the song's sharp melodic edge. "The Revolution" pushes in the opposite direction, downplaying rhythm in favor of a swooning melody.

He also found himself tapping into sounds and styles that recall some of the Talking Heads' poppier moments ("Like Humans Do" and "Broken Things" being prime examples).

In various interviews, Byrne has admitted that early in his solo career, he tried to avoid anything that would evoke his former band. These days, he's more willing to embrace some of the musical trademarks of the Talking Heads, although he approaches such familiar styles with considerable care.

"There was one [song] that I did that didn't make it to this record that sounded very much to me like an old Talking Heads song," Byrne said. "It was a good song, but it didn't fit on this record. So that's still part of my makeup. But also I'm aware that it's a danger, that I could slip into a well-worn path there. It's something that comes a little bit too easily."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

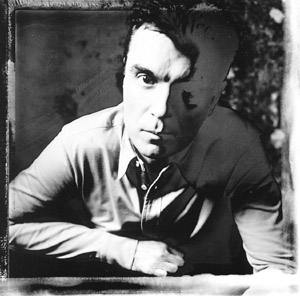

Easy on the Ears: Byrne was unnerved to find he'd actually written some pretty music.

From the February 13-20, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.