![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Count Us In

Uncounted residents in the 1990 census resulted in the loss of $15 million for the county. Community organizers say it won't happen again.

By Jessica Lyons

LAURA SEGURA Gallardo sits behind a desk covered with hot pink Census 2000 yo-yos and buttons that read "Watsonville Be Counted!" and "¡Hágase Contar!" The phrases have been a city mantra for three years now. In 1990, the one-day, nationwide population count missed more than 5 percent of Watsonville's population--most of whom, according to the Census Bureau, were Latino. Watsonville officials estimate the city lost between $8 million and $12 million in federal dollars as a result--money that could have built more roads or low-income housing, or funded better education, health services and youth activities.

Determined not to repeat the mistake, the city conducted an independent neighborhood canvassing effort in 1998 and found 938 homes that were not listed on the U.S. Census Bureau's address list. The addresses altogether represent about 3,200 people who have now been added to the list, and without whom another $8 million in revenue between 2000 and 2010 would have been lost.

One wall in Gallardo's office, a portable trailer on West Front Street, is piled high with boxes of census pens, pencils, yo-yos, t-shirts and plastic cups. Armed with these knickknacks and $47,000 in city and federal funds--and with a three-year head start and head of steam behind her--Gallardo, a senior administrative analyst for Watsonville, says the Census 2000 numbers will tell a different story.

"The city has realized the loss of revenue from census data, the impact is absolutely tremendous, it effects everyone," Gallardo says.

Federal grants are based not only on population but also on demographic information developed by the census. Uncounted Watsonville youth in the 1990 Census resulted in less money for worthwhile youth services.

"If we had had a better count in 1990, we would have received more money to improve recreational programs for kids," Gallardo says. "Our baseball leagues, soccer leagues, drop-in center are all based on census data." Extra funding could also have paid for additional staff members for homework centers.

About $35,000 was allocated to Santa Cruz County by the state Complete Count Commission, $23,000 going towards minority outreach and education. Federal programs are also in place to achieve the goal of decreasing the undercount rate, especially among minorities.

Gallardo doesn't want to see Pajaro Valley residents shortchanged again, but she realizes that trinkets and a few thousand dollars won't ensure that the surveys don't lie.

A Census How-To: Census info is there for the asking.

Stairway to Democracy

CENSUS INFORMATION is the source code of democracy. Where political boundaries are drawn, how the federal budget is allocated--in short, how federal power and money devolve--flow from the building-block information developed by the U.S. Department of Commerce's Census Bureau.

"Most federal grant monies are requested per capita," explains Judy McTighe, the census office manager for Santa Cruz County. "For example, if you are going to build a school, you request X amount of funds per student. School lunch programs are federally funded, based on the census statistics that provide information on school-age children. The census tells us if we have a need for bilingual education, and is used to award bilingual education grants. When you request FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] monies for a natural disaster, the people that are displaced are measured by census numbers. FEMA monies are distributed per capita."

Under the circumstances, it's not hard to see how the Census Bureau came up with one of its slogans: "todos cuentan"--everybody counts.

That includes the homeless, college students living in dorms, and illegal immigrants living in the U.S. But historically, Latinos, blacks, American Indians and children have been underrepresented in the census. One in every 20 Latinos was not counted in the 1990 census, and for Santa Cruz County, those numbers were even higher. The undercount hit hardest in the northern tip of the county, the Beach Flats neighborhood of Santa Cruz and Watsonville, where between 3 and 7 percent of residents were missed. Of those, between 33 and 85 percent were Latino.

Among Latinos there are several reasons people avoid the census. The most obvious is fear of deportation. The census is charged with counting everyone, not just citizens and documented legal residents. Because they use such resources as food-distribution centers, natural disaster relief and health services, the census is legally required to count undocumented workers. But despite a near iron-clad guarantee of confidentiality of census information, many undocumented workers will not risk filling out the census forms.

Recent news reports of undocumented workers living in substandard housing reveals the wariness some Watsonville residents feel about government agencies. In September, city inspectors evicted 24 undocumented Watsonville workers living in an illegally constructed basement. The city provided motel vouchers for the workers, but they "disappeared into thin air," says Rafael Adame, Watsonville's assistant community development director.

"Most of them were afraid of possible government retribution when their housing situation was brought to light," Adame explains. "We made every effort to meet with everybody we could find living there. Some benefited, but most didn't."

Other challenges to an accurate census count include language-barriers, low-education rates and a basic mistrust of government. According to Adelante, a Latino resource center in Watsonville, the majority of Pajaro Valley's nearly 14,000 migrant workers only live in the area between April and November, during growing season, and return to Mexico the rest of the year.

For the county, this means outreach efforts need to start several months, or even years, before Census Day on April 1--the deadline to mail in census surveys. After that date, the Census Bureau will send out follow-up forms, reminding residents to return their surveys. If that doesn't work, field workers will walk door to door, visiting homes that have not answered census questionnaires. Migrant workers returning to the Pajaro Valley after April 1 will also be counted, largely through door-to-door outreach.

Photograph by George Sakkestad

A Familiar Face

ULTIMATELY, EDUCATION about the census for difficult-to- reach populations must come this way: From the bottom up. "It's very important that people get the message from someone they trust," Gallardo says. "This is a very grassroots effort. That's going to be key to its success."

People who are wary of government questionnaires will be reassured by familiar faces that their answers are 100 percent confidential. By law, the Census Bureau cannot share survey answers with the IRS, FBI, Welfare, Immigration, or any other government agency. Even households receiving welfare money for more children than they actually have will be safe. Illegal businesses won't be turned over to the IRS, and renters living in crowded garages won't be reported to county health or building-code officials.

The Santa Cruz County and federal Complete Count committees, along with city councils nationwide, are spending millions of dollars on census outreach, throwing Census 2000 parties, mailing out census flyers, sticking census reminders on paycheck stubs and water bills, and hosting info nights at schools and community centers. Temporary workers will walk door to door and staff census information centers in hard-to-count areas.

Ken Cole, director of the Homeless Community Resource Center, says his organization will hire workers to help census counters, and will hand out free socks, backpacks, underwear, food and other incentives to encourage homeless individuals to fill out the survey.

"The key is hiring people who can introduce the census takers to the homeless and be a bridge to connect census takers with individuals who might otherwise not be counted," Cole says.

At UCSC, where students comprise another traditionally hard-to-count population, administrators are working to recruit students as temporary census workers. Jim Carter, a Cowell College administrative officer, says his goal is to have at least four student workers at each of the university's eight colleges. So far, he's had 50 students call or email him, asking him about census jobs.

"We've arranged to be a test center [for census hiring], and we're trying to recruit as many students as possible to be census enumerators and help count students on campus," Carter says.

Do the Math

THE CENSUS form is supposed to be mailed out to every address, completed by the entire household and returned by April 1. But since 1970, the response rate has dropped 10 percent each decade. For Census 2000, this would mean only a 61 percent response. Attempting to compensate for this, the Clinton administration wanted to use statistical sampling in addition to the head count. But a federal court shot down the proposal.

While no one can guarantee the response rate won't drop again this year, "it won't be because we didn't have enough services," says Fred Casillas, a U.S. Census Bureau representative, based in San Jose.

The data are used to allocate $180 billion in annual federal funding for health services, child care, education, transportation, road repair and other services. Ethnic, socio-economic and racial statistics drawn from the survey determine the need for state and federal services and programs.

Census 2000 will also be used to redraw district lines for the U.S. House of Representatives. Casillas says an accurate 1990 head count would have gained an additional congressional seat for Northern California. Preliminary Census 2000 predictions are that Northern California may lose a seat this time around, even though California has gained population.

"Some of the Northern California seats don't have enough people in them, and some of the Southern California seats have too many," explains local Assemblyman Fred Keeley. "California's population has grown over all, over the past decade. That means that California will gain a few, probably four or five congressional seats, and given how the growth has occurred in the past decade, most of those seats will probably be created in Southern California."

Head Count

FRED CASILLAS IS A ROBUST man with thick graying hair and soft eyes. A bilingual native of Watsonville, Casillas moves easily among the people he's trying hardest to reach, such as migrant parent groups, Pajaro Valley schools, and adult education classes.

"A big part of my job is to build awareness, to really promote the upcoming census," he says. "We preach, 'The census is coming, apply for a census job, get ready, here it comes.'"

At each presentation he teaches "Census 101" with fervor, explaining what the census is, and why it is important to be counted. He talks about how census data translate into funding, political representation, local policies and programs. And he encourages everyone 18 and older to apply for one of the more than 600 temporary census jobs, which pay well--$15.50 an hour plus mileage.

Sometimes only 20 listeners show up, and sometimes Casillas preaches to 150 or more. With every assembly, people stay after to talk, ask for a census poster to give to their friends, or request he visit another group.

Tailoring his message to each community, Casillas describes federally-funded migrant education programs to the seasonal farm workers and hands out census balloons and stickers at elementary schools.

"I talk to them in their own language," he explains, whether that be Spanish, Spanglish or a system of rewards.

But the most important truth of Casillas' gospel is confidentiality.

"That is a red-hot issue," Casillas says. "It's very important with the migrant population. They are worried that if they give up the information needed for the census, they will be returned to their country. We stress that in the history of the census, there has never been a break in confidentiality. No one has ever been handed over to the INS."

Still, there's always concern that no matter what Casillas says, a large percent of Santa Cruz county won't be counted, and more federal funds will be lost over the next 10 years. In 1990, 2.7 percent of Santa Cruz County residents were not counted. This year, city and county officials are shooting for 100 percent, but will be happy to beat the last census count, which Gallardo calls "atrocious."

Present & Accounted For

FOLLOW-UP COUNTS by the Census Bureau, called the "Accuracy and Coverage Eval-uations," indicated that children were grossly under-counted in 1990, by about 50 percent nationally and by percent in Santa Cruz County. This year, Complete Count Committees and Census Bureau representatives are targeting schools and parent groups. Casillas says he hopes the grade school kids he visits will bring the census balloons and fliers home to their parents. Eventually, enough "Be Counted" pens, highlighters and paper weights lying around will remind parents to count themselves and their children.

Last October the Pajaro Valley Unified School District's Migrant Parent's group hosted a census night, telling parents that ignoring the census translates into lost funds for migrant services.

"In order to get migrant parents prepared, we needed to start early," says Dr. Paul Nava, the school district's director of migrant education. "Many are gone right now, and they are not going to return until March. By starting early, we have already reached over 100 parents and informed then about what they need to do to fill out the survey."

Starting this month, more than 20 census help centers and language assistance centers will open throughout Santa Cruz County, targeting the immigrant community.

"We will help people fill out the survey; we will be going door to door, telling people to check 'Spanish' in the language-preference box on the post card, and if they do receive the survey in English, we will have copies in Spanish," says Julie Albores, the program director for Adelante in Watsonville. Albores says that more than 60 percent of Adelante's clientele are seasonal farmers who work in the Pajaro Valley between April and November and then return to Mexico.

The Familia Center, a Latino resource center that provides food, classes and translation services in Beach Flats, began promoting the census in December. During the holidays, Familia Center director Yolanda Goda handed out census buttons and magnets. Since then, she has done radio shows on La Campesina, 107.9 FM, answering questions about the census, and is helping to plan census booths and promotional events for the upcoming Clam Chowder Cook Off, and the annual Beach Flats Spring Clean Up in April. Condensed census brochures in Spanish and English will be distributed to Familia Center clients.

Goda says she also hopes to hire four Familia Center-area neighbors to walk door to door assisting with census surveys and to staff the Familia Center census questionnaire and language assistance center.

"Agencies like ours are going to be banking heavily on trust within the community," she says. "If we want change at the local level, we have to step up to the plate.

"Our toughest job is going to be really just overcoming the fear of governmental forms, and getting across to people that no one can access your information. We may lose some of those people, but on the other hand, we're hoping there may be just one member of the family that fills out the form for the entire family--or if there are illegal renters, that [the landlord] will count them, whether they want to be or not."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

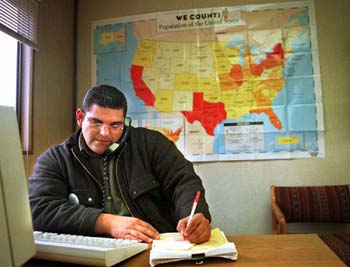

Countdown: Felipe Hernandez works the phones at Watsonville's Neighborhood Services Division Census information center.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

United We Stand: Watsonville's Census Committee throws fiestas, walks door to door and visits community groups, attempting to count 100 percent of the city's residents for Census 2000.

United We Stand: Watsonville's Census Committee throws fiestas, walks door to door and visits community groups, attempting to count 100 percent of the city's residents for Census 2000.

From the February 2-9, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.