![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Picture This

A provocative biennial shows off the formidable talents of UCSC's studio art faculty

By Julia Chiapella

AT THE DAWN of what's been termed a New World Order, it's fitting that Don Fritz's work opens the "Faculty Works: 2001" exhibition at the Mary Porter Sesnon Art Gallery. Like the Brave New World it implies, this New World Order is part assurance, part threat, and Fritz plays with that collective ambiguity, concocting a soup of stupefying imagery.

It's become Fritz's trademark, this carefully crafted helter-skelter of Americana, and it seductively leads the way into an exhibition that lays out the best of contemporary works by UC-Santa Cruz fine arts faculty. And while some of the works are more appropriate to another type of venue--notably Nobuho Nagasawa's models and sketches for public art installations--the work in the Sesnon Gallery and accompanying Faculty Lounge is a broad and varied collection.

Fritz mesmerizes with his Ring of Fire, Pot of Gold, a large mixed-media painting that reveals as much as it conceals. Images of innocence and danger whirl around in a cacophony of visual anecdotes that threaten to undermine reality's fabric. Whether we are looking at smiling children playing a circle game or the partially revealed image of a fetus, Fritz manages to inject almost paralyzing complexity into his work yet somehow retain in it a sense of calm detachment.

Frank Galuszka's Coyote in the Kitchen is a large piece that dabbles in the sunny light of a kitchen gone awry. There is something of the Dutch Baroque painters in Galuszka's focus on a single figure in a self-revealing moment. But Galuszka contemporizes that figure; brings it into the light, throws open the door and lets nature wreak havoc. The resulting narrative embodies elements of mysterious delight that are well supported by Galuszka's brush.

In a similar homage to the brilliance of the natural world, Jennie McDade's landscapes bring a reverential sense of color and texture to the fading sun as it cascades across the inhospitable magnificence of the desert. Her Yucca, the opening piece in the Faculty Lounge portion of the exhibition, is a soothing yet richly evocative landscape highlighted by exquisite brushstrokes and set to the splendor of richly hued blues and oranges. This brutal landscape so tenderly rendered makes for an exquisite balance.

Without touching on all of the artists in this exhibition--a disservice to all but a slight to none--it should be noted that there are lovely pencil drawings of insects by Hanna Hannah and photographs by Ken Alley, Norman Locks and Elliot Anderson. Mention should also be made of E.G. Crichton's Fugit Hora: Forget Me Not, a video sculpture cleverly blending the nature of a book with the artistry of moving images.

Serving as a central piece and sure to generate the most controversy in this show, Elizabeth Stephens' Presidential 2000 is an "intermedia" piece that defiantly screams volumes. Atop three white stools sit three gleaming speculums. White lab coats hang in front of two of the stools and are periodically sprayed with blue and red ink from inside the speculums. The middle stool sits in front of a U.S. flag. When the spraying is complete, the third speculum snaps open and shut to the words "I'm Sorry." It's a perfect fit for the New World Order.

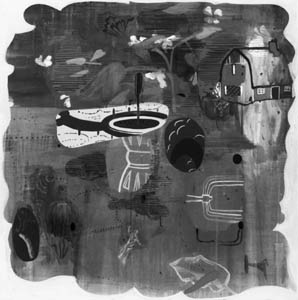

The only misfire here other than Nagasawa's misplaced landscape concepts is the work of Miriam Hitchcock. While her solo show at the Eloise Pickard Smith Gallery in May 1998 was brilliantly moving, the three pieces here can't find their focus. They still contain the rich, well-rendered images that are her stock in trade, but lack the strength that would move them into a more formidable and meaningful realm.

Reflecting both assurance and threat, "Faculty Works: 2001" is a laudable first step into the "real" new millennium.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Water Works: Miriam Hitchcock's 'Always & Forever (Fountain)' is one of the pieces featured in 'Faculty Works: 2001.'

UCSC Studio Art Faculty Exhibition is at the Mary Porter Sesnon Art Gallery and Porter Faculty Services, Porter College, UCSC, through Feb. 11. Gallery hours are Tuesday thru Sunday, noon-5pm.

From the January 31-February 7, 2001 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.