![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

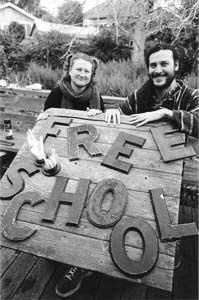

Photograph by Stephen Laufer

A Is for Anarchy

Shunning tuition fees, bureaucracy and dogma, intrepid Santa Cruzans start their own school

By Darren Keast

CAROLINE NICOLA WANTED to learn how to stilt-walk, so she decided to teach a class on it. Well, not teach exactly; facilitate was more like it--she Xeroxed off some stilt-making instructions, tracked down a few expert stilt-walkers for guest lecturers, posted a time in the Free School Santa Cruz schedule and opened the backyard of her shared house to other interested newbies. At the end of the Saturday morning session in November, all 10 students walked away not only grinning and grass-stained, but one new skill and nine new acquaintances richer.

In a similar burst of self-empowerment nine months earlier, Nicola and her original partner Laloo Mendelson decided to start their own school. They didn't have any experience doing that either, but here again, that fact seemed irrelevant. Sharing a love of education and an affinity for the do-it-yourself ethos they picked up in the activist community, the two young women founded Free School Santa Cruz, a grassroots, community-driven, skill-sharing network free of both tuition fees and bureaucracy. Nicola and Mendelson had heard about the basic idea of a free school--which dates back to the 1960s but re-emerged in the '90s as anarchist principles gained prominence in underground political circles--but didn't know of any specific ones on which to base theirs.

They chose as guiding inspiration a quote from Malcolm X, which reads: "We ourselves have to lift the level of our community to a higher level ... make our own society beautiful so that we will be satisfied. ... We've got to change our minds about each other. We have to see each other with new eyes ... We have to come together with warmth." So from the beginning, the school's charter was explicitly radical--education for creating a better world.

"Even though a lot of Free School classes may not be political in orientation," Nicola says, "just the structure of Free School is very political. Our communities are disconnected and atomized, so this is a way to create a structure where people can come together around a very basic idea--sharing your skills. Sharing is really commonplace to our humanity, and it's just changed now that our lives are so commodified, so it's bringing back something that I think is really fundamental."

Free Trade Zone

Today, Free School's core organizers are Nicola and Armando Alcaraz, a board of regents of two (Mendelson took on a full-time job). The notion of free education particularly resonates with Alcaraz, who studied at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City--the university that students shut down for a year over a proposal to start charging tuition. Together, the pair assemble the bimonthly schedule of classes (available in paper form around Santa Cruz, and on the web at www.dobius.com/freeschool), help potential teachers format their proposed courses, find space for the classes, and offer and attend classes of their own.

The offerings so far have been a mix of workshops and discussion seminars in the practical, such as vegetarian cooking, Permaculture gardening, résumé writing and tips on buying a home; the radical, including a biweekly anarchist discussion and a Howard Zinn reading group; and the artistic, with the current schedule listing such classes as Native American Pine Needle Basket Weaving and the Lets-Have-Fun-With-Collage Workshop-Party. Would-be teachers simply call in or submit a proposal through the website, Nicola and Alcaraz look it over, and the new course goes into the upcoming schedule. "Basically, as long as a class doesn't contradict our mission statement, it will make it," says Alcaraz. No classes have been turned down for content reasons so far.

The free-school concept embodies numerous points on the anarchist's wish list, including the preference for decentralized and nonhierarchical structures, anti-capitalist systems of exchange and personal and community enrichment outside the reach of corporations and institutions. Not surprisingly, free schools have taken off in well-known anarchist hubs like Eugene, Portland and Seattle.

"A free school to me is just a longer extension of an anarchist skillshare," says Jean Cadwell, who organizes the anarchist discussion group. Skillshares, like the weekend-long one offered each spring in Berkeley, are ways for activists to network and learn in a do-it-yourself framework. "And it's very collectivist, because it's something that creates a community around it. The other thing is that it makes people realize they have skills and abilities that they can share with other people and are worth something to their community, so it bolsters their self-worth as well."

The inclusiveness of the class offerings is such that they don't alienate those of nonradical or nonanarchist persuasions, however.

"I'm attracted to it in spite of the word 'anarchy'," says Carol Fox, who has taught a cooking class through Free School and facilitates the creative writing group and the Crone's Club, a circle for creative women 50 and older. "I'm kind of a spiritual hippie, not a political hippie--there were two kinds of us. So I go even though they talk about anarchy a lot, because I like the spirit of sharing what I know, and it's a great way to meet people with similar interests."

Politics to Permaculture

While both Nicola and Alcaraz say they think of the school's reason for being as overtly political, neither operates it as if they have an ax to grind. Anarchism isn't mentioned in the mission statement, and many of the teachers don't have connections to any activist groups. For instance, local lawyer Gregory Reeves-Wilson has taught two classes, and Brian Barth, the initiator of the Permaculture class, describes himself as "not a political person--not directly anyway."

Alcaraz points out that "Free School goes beyond the activist community, in that it's creating a whole institution in itself that is community-based, so the work to sustain it brings people together. It's also a way of empowering and feeling that you can do something outside the prescribed institutions--nobody has to tell you that you're a teacher, and you don't have to go through any process to become a student. You can learn from the people next door."

Free School has already worked to foster other networks beyond its initial scope--the creative writing circle has continued on after its originator was no longer able to attend, and the Permaculture class spawned a Permaculture guild, which occasionally meets on days other than those scheduled through Free School and has a lively email discussion list of its own. Alcaraz has also heard of some Watsonville residents who are interested in starting a Free School there.

The response has been so good in fact that the work required to run Free School is threatening to overwhelm its two harried organizers. They say that in order to have it grow to the next stage, they'd ideally like to add another core member or two, and of course, part-time volunteers are always needed. Nicola also has been looking into the possibilities of getting a grant for Free School, which fittingly she did by attending a grant-writing class offered through the school.

"It'd be nice if we had a central space--other free schools are run out of an infoshop," she says, referring to the situation of the Portland Freeskool, which meets at the Liberation Collective's anarchist library in downtown Portland. "But it's also nice to have it spread out and grassroots. Going into somebody's home that you don't know, having them teach you how to cook, and sharing a meal with them is really exciting."

"That's what grounds it in everyday life, the actually connecting with people," Alcaraz adds. "And that itself is a political thing."

We think Malcolm would be pleased.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Curriculum Vital: Through Free School Santa Cruz, Caroline Nicola and Armando Alcaraz offer classes that range from the radical to the practical.

Curriculum Vital: Through Free School Santa Cruz, Caroline Nicola and Armando Alcaraz offer classes that range from the radical to the practical.

From the January 30-February 6, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.