![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

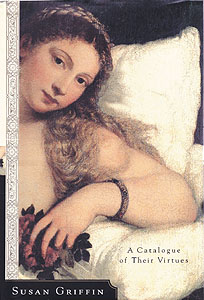

Virtuous Vixens

Feminist author Susan Griffin turns her attention from angry men to resourceful women in a provocative social history

By Barbara Baer

SUSAN GRIFFIN'S Women and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her appeared in the late 1970s. Since then, so much has been written on women as earth nurturers vs. men as makers of weapons and desecraters of nature that it's hard to remember how original and courageous Griffin's work was two decades ago. Her radical perceptions about the patriarchy, the threat of nuclear war and environmental degradation influenced so many other writers that her ideas have passed into the mainstream, like water finding its level.

Through the '80s and '90s, Griffin continued to attack ambitious, controversial, dark themes in books that were backed by extensive scholarship and a lucid, lyrical prose. She took on pornography, rape and the perpetrators of violence--in all, 20 books, including A Chorus of Stones, a meditation on the psyches of men who made weapons of mass destruction, which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

Twenty years later, Griffin's outrage and prophetic anger toward male violence have been transformed in The Book of the Courtesans (Broadway Books; 269 pages; $24.95) into praise of the resourcefulness of women. Neither born to power nor elected, courtesans influenced culture and politics from their salons and canopied beds; always on public display, they were arbiters of fashion and served as muses and models for the great writers and artists of their day. For Griffin, women and nature have evolved into women and artifice, or perhaps better, the courtesan who has risen above her class and the limitations of a male world has herself become a force of nature.

I never found Griffin's tone so relaxed or conversational as it is here. Does this evolution mean that Griffin herself is more at ease in the world? I wish I knew, because her somber writing was so meaningful to me in the past that the lighter Griffin took me by surprise. I do know that she suffered for years with chronic fatigue syndrome, becoming so weak at times that friends had to turn pages of books so she could read in bed. Perhaps coming back from such an illness made all things of the world more loved, more filled with light.

Several years ago, I heard Griffin speak at the Bioneers conference in San Francisco. She was just recovering her strength and seemed fragile, but her thinking already had evolved away from separation of the sexes, and she argued passionately for men and women working together to save the Earth.

Earthly Delights

Griffin's appearance for a recent reading from Courtesans went well with her subject. I remembered her dressed in minimalist black and white, with no makeup--tonight she was elegant in a wine-red blouse with transparent chiffon sleeves and red lipstick. She seemed to be enjoying herself and established an instant rapport with her audience of mostly women, entertaining us with juicy tales of Greek, Roman, Venetian, British and particularly Parisian courtesans who loved and were loved for providing earthly delights.

Kings, dukes and other powerful male protectors got high marks for appreciating women and material pleasure, in contrast with Griffin's previous books, in which males walled off consciousness from feelings, soul from flesh, resulting in hatred and destruction of matter and the feminine.

Now the courtesan is described by a male admirer as "the apotheosis of Matter," words that apply to The Book of the Courtesans as a whole. In scene after scene, the body of woman is golden, glimmering, brilliant with jewels, rich in silks, a play of light and scent and sound. The shadows of breasts and curve of buttocks long to be explored.

"Is that a shadow cast by her hand or just the upper edge of the nipple that we can barely see above the resplendent fabric?" Griffin asks. Of course there are risks to letting oneself be enchanted, but they are risks worth taking. "Like eros," Griffin writes, "beauty opens the heart, softening not only the gaze but intent itself. Under either the influence of beauty or love, indulged to linger, as we sink into the realm of feeling, we forget to calculate our losses."

Since the time of the Greeks, courtesans have kindled the imagination and aroused the flesh. They were distinct from prostitutes and geishas, different from mistresses. True courtesans were independent operators, celebrated women who gave their patrons one night of the week or month.

Some like Sarah Bernhardt and Coco Chanel began as courtesans and became artists, while others married into great estates and titles. For most women, becoming a courtesan was first of all a way out of poverty. The majority of women Griffin describes came from the working class. In Paris, they often labored from dawn to dusk as seamstresses in the penumbra of attic rooms. (They were called grisettes for the bad lighting in which they worked; their lives were gris, or gray, like mice.)

But at night, these tired girls made themselves up and dressed brightly for the balls and parties where they might meet a wealthy protector. From there, they might build on their first successes by learning social graces and how to dress and make love from worldly gentlemen. Some courtesans came from the other end of the social hierarchy, dropping down from the aristocracy because of scandal or economic reverses, choosing adventure, pleasure and material comfort over genteel poverty.

Tough and Tender

Of course the way up to social prominence and wealth didn't come easily, and only the gifted became celebrated figures at court or in drawing rooms. Courtesans, Griffin tells us, had to be tough and tender, erotically aggressive one minute, solicitous the next. In a society where males dominated and sexual prudery reigned, they were freer than other women and most men. Courtesans, Griffin tells us, "censored none of their abilities."

"In essence, all courtesans, no matter how rouged or bejeweled they were, had to have the virtues of both men and women. ... In the unpredictable realm of eros, that which pleases most is not simple submission. The secret they discovered is a paradox: Those who would dominate are soon bored by their partners. And correspondingly, desire is excited by the presence of a spirited soul--independent, unpredictable, incandescent with the mysteries of a separate being."

Griffin evokes the streets of Rome, the royal bedchambers of France, the drawing rooms of England, Venice in its golden epoch and the Belle Epoque in Paris, using imagery drawn from diaries, paintings, landscapes and cities. However, at a certain point, the quantity of detail, titles and estates, the luxurious clothing and furnishing courtesans acquired ends up sounding the same, as do the descriptions of besotted high-born lovers.

Curiously, Griffin doesn't linger much on women's relationships with other women--possibly because such an inclination wasn't lucrative until lesbian American heiresses reached Paris in the early 20th century and had money to spend on themselves. The only homosexual lovers described in detail are two men, Vaslav Nijinsky and Serge Diaghilev, courtesan and patron respectively. I found the relationship of artist to impresario, younger to older man, the most interesting in the book.

Here Griffin explores the strain and constraints of the power imbalance between two men more dynamically than she does in any relationships between men and women.

Personally I missed a section on the downside of courtesan life. There's nothing to match the portrait that Colette painted of the aging seductresses Léa and Charlotte in Cheri and The Last of Cheri. I also missed the stories of seamstresses and music hall soubrettes who didn't make it out of poverty--those spectral waifs immortalized by Jean Rhys, evoked from the gutters of Paris by Louis-Ferdinand Céline in Journey to the End of the Night. Frail women would have balanced Griffin's picture of rounded bodies and sparkling jewels, but poor, pitiful girls didn't make the pages of courtesan history.

What I liked even less in The Book of the Courtesans was the way that Griffin put words into the minds of male lovers. Her imagined men go into raptures over female underclothes, toilette, the shadowy cleft between breasts. They have metaphysical responses to sexual experience that are hard to believe.

There is one photograph of a portly, former courtesan named Alicy Ozy that speaks a thousand words. Ozy is leaning over the back of a satin chair, her ample body covered in brocade, her eyes intelligent, kind, tired. Earlier, we've seen a picture of Ozy in her fabulous youth. There she reclines, white arms over her head, framing a face of classical purity, naked breasts and shadowy underarms a vision of erotic longing on a bedcover. Can these two portraits truly be of the same woman? We may wonder.

The Joy of Living

Griffin's final chapter is an epilogue, a coda, that fills out the biographies of the major courtesans in a pared-down prose that I wish she had used more throughout her book. The women exist here in the span of their extraordinary lives.

The matronly Ozy lived out her years in ease and at her death willed a fortune to the children of impoverished actors.

Lola Montez, an Irish girl who posed as Spanish nobility and rose to dizzying heights of wealth and power as the companion to Ludvig of Bavaria--she and Ludvig were arrogant, hot-tempered and self-destructive, a stress on the final adjective--nearly lost her life to an angry mob. Lola, always an escape artist, still managed to cover an incredible amount of ground after Ludvig's death, seducing men on several continents, writing books and, in her final days, becoming a counselor to prostitutes at the New York Magdalene Society. She died following a stroke at 40.

I relished the story of La Belle Otero, one of a trio of famous Parisian courtesans of the Belle Epoque. The photograph of Otero in her youth showed a woman absolutely made for the joy of living. She became immensely successful, much loved and very rich, but due to a weakness for gambling, lost her fortune on the Riviera. Fortunately, she was so revered that the casino owners subsidized a simple living for Otero in Nice to the end of her long life.

Griffin leaves us with an admiring glance at this elegant woman: "She never lost her style. Even in an altered, elderly shape, when she entered a room, heads turned."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

The Pleasure Principle: Susan Griffin says that 18th- and 19th-century courtesans turned the tables on men, enjoying intellectual, sexual and financial freedom.

The Pleasure Principle: Susan Griffin says that 18th- and 19th-century courtesans turned the tables on men, enjoying intellectual, sexual and financial freedom.

From the January 30-February 6, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.