![[MetroActive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Forever Young

A new exhibition about Woody Guthrie reveals the man behind the folk legend

By Tai Moses

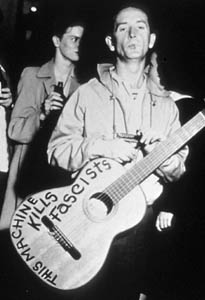

HIS GUITAR was emblazoned with the slogan This Machine Kills Fascists. He didn't care about making money, being famous or topping the Billboard charts. He wrote more than 1,000 songs, and when he died, at 55, he left behind at least 2,500 complete lyrics.

There is tragedy all over this story; there is fire, illness and romantic calamity; there is death and disappointment. And there is the opposite of those things--life, with all its commotion and beauty. And so we have the myth of Woody Guthrie.

Woody's story is one of those considered to be distinctly American--that is to say, he came from nowhere (in myths Oklahoma is often a stand-in for nowhere) and became an enormously influential artist. Thirty-four years after his death, Woody still inspirits the American imagination.

But who was the real Woody Guthrie?

Woody's youngest daughter, Nora Guthrie, wondered the same thing about her father, who was in the hospital for most of her childhood and died of Huntington's disease when she was 17.

About eight years ago, Nora found a cache of her father's papers in the office of Harold Leventhal, his last manager. She sat down on the floor surrounded by the boxes and that's how the Woody Guthrie Archives were born.

"In looking through my dad's notebooks and diaries and lyrics, I discovered a lot about my dad," said Nora, 51, at a recent talk at the National Steinbeck Center to celebrate the opening of the exhibition "This Land Is Your Land: The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie."

"I discovered that about half of what I knew about my dad wasn't true. Creating the archive has given me an opportunity to know him without Huntington's."

The show, a collaboration between the Guthrie Archives and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, is the first-ever museum exhibition about Guthrie's life and music. Along with portraying the Woody that most of us know--folk legend, protest singer, rambling man and union organizer--the exhibition paints a fuller picture of Woody Guthrie as a father, husband and lover, poet, novelist and newspaper columnist, sketcher, cartoonist and painter. At its best, the exhibit liberates Guthrie from his status as legendary cardboard folksinger and hero of the left and grants him the complexity that has long been his due.

Pastures of Plenty

I WENT to the Steinbeck Center to see the exhibit the week of my father's birthday. He's been dead a year now, and Woody Guthrie was one of his lifelong heroes. My father lived in Coney Island on Neptune Avenue about the same time Woody and his family were living around the corner on Mermaid Avenue.

So it seems inevitable that I looked at the exhibit and listened to the songs and watched the videos of Woody and Cisco Houston and all the others through the eyes and ears of my father, who was himself a card-carrying lefty, and I marveled and mourned and ended up getting my own personal loss mixed up with our national loss of Woody Guthrie.

But when I started to tease it apart, I realized it didn't matter, because Woody was all for stirring up feelings in people and showing how one thing was connected to another. That's what his music was about: "I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world."

Woody Guthrie was not a big man, but he had a large and irrepressible spirit. His creativity spilled out of him in a cataract of energy that filled up all the spaces of his short life in no time at all. Representing this extravagant life behind Plexiglas display cases was obviously a challenge for Nora Guthrie and the rest of the curatorial team.

The exhibit is arranged in 10 modular stations, the stations of the cross, if you will, and viewers may take a chronological stroll through the singer's life or skip around and get the stories all out of order, a sort of "Woody's Greatest Hits." There is Woody's Oklahoma period, his Dust Bowl and Great Depression period, his California period, his Union Organizing period, his Merchant Marine period, his New York period. Finally, there is the era of Huntington's disease, and then a presentation about his musical legacy.

The panels of the stations are made of enlarged reproductions of his writings and artwork. The listening stations feature previously unreleased music from Smithsonian Folkways collection, plus film footage and recordings of his rough, twangy voice.

No matter where he was, Woody wrote constantly. He left behind a remarkable treasure trove of written material: diaries and journals, letters and postcards, address books, poems, song lyrics, story manuscripts, newspaper articles, prose fragments--words of all kind, typed or copied out in his crabbed script on napkins, butcher paper, newsprint, envelopes, anything that was available.

He was also a prolific visual artist; his estate contains more than 600 artworks--and that's just what he kept, since he gave the art away as fast as he made it. The show features about 50 of his paintings and drawings and like his songs, they depict his uncanny ability to get inside other peoples' realities.

Also on display are all kinds of memorabilia and personal objects: the gray Royal typewriter he wrote on, concert ticket stubs, a brooch he gave his wife, Marjorie. Woody's mandolin is here, and so is his fiddle, hand-carved with the mottoes, "This machine killed 10 fascists" and "Drunk once, sunk twice."

There's an enlarged copy of a heartbreaking letter he wrote after his and Marjorie's 4-year-old daughter, Cathy Ann, died from burns she sustained in a fire in 1947. "We had a simple cremation with no crying funeral. ... Cathy was happy to her last breath and I think that she had best see us all be the same way in our future works and dreams to come."

In the next-to-last display are two large cards with YES and NO printed on them. Toward the end of his life, when Huntington's had eaten away his mind and he could no longer speak or control his gestures, Woody used these cards to communicate with.

Dusty Old Dust

ONE THING about "This Land Is Your Land"--it is a very polite hootenanny, quiet, orderly and clean, and Woody's music is playing, but the volume is turned down low so museum-goers can concentrate on what they're reading and looking at. Woody was a funny man, and he must have known he had an extraordinary gift, but he was also humble and understated and he would have probably been embarrassed by the formality and the hushed museumy atmosphere that lies over all his stuff.

I suspect that if Woody's ghost popped in to do some poltergeisting, his first order of business would be to throw some dirt on that gleaming concrete floor and peel back the ceiling to let in some sky. Woody, the Dustiest of the Dustbowlers, was not one to stand on ceremony. He might fire up a stogie and let the smoke waft around and take all those relics out of their cases and let folks put their grubby paws on things, especially that sad fiddle, quiet as a stuffed tiger.

Does "This Land Is Your Land" reveal the "real" Woody? I don't know if such a thing is possible. There are great stories and memories and history to be found here, but one thing that isn't here is Woody. The best place to find Woody Guthrie is still in one of his songs, and those are everywhere and probably always will be.

He was born and he worked and he rambled around and he wrote and sang songs and then he got sick, and through it all he continued to give a damn about other people, about their lives and their troubles, both the daily small oppressions that wear us down as individuals and the larger injustices that try to destroy us as a people.

That's what sets him apart, and that's why Woody Guthrie continues to matter to people; because they mattered to him. "The worst thing that can happen to you is to cut yourself loose from people," he wrote. "And the best thing is to sort of vaccinate yourself right in to the big streams and blood of the people."

Maybe the most important thing this exhibition achieves is to prove that Woody Guthrie did what he did every day of his too-short life out of the most uncomplicated kind of love. That's something. Some people might even say it's everything.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Courtesy Woody Guthrie Archives

This Land Is Your Land: The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie is at the National Steinbeck Center, 1 Main St., Salinas. Open daily 10am-5pm; $3.95-$7.95; ends March 4; 831.775.4720.

From the January 24-31, 2001, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.