![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

|

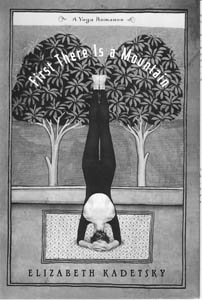

Elizabeth Kadetsky's 'First There Is a Mountain: A Yoga Romance' is available from amazon.com. |

Stretch Marks: Elizabeth Kadetsky has chronicled her yoga obsession in 'First There Is a Mountain.' She speaks at Bookshop Santa Cruz Jan. 21. Yogi Bare UCSC alum Elizabeth Kadetsky exposes the highs and lows of her intense relationship with the art of yoga By Jessica Neuman Beck Elizabeth Kadetsky refers to her memoir, First There Is a Mountain, as "A Yoga Romance." At first that seems a little bizarre, but once you get into the book, you realized it's a fairly accurate way of putting it. A former Santa Cruz writer known for her work at seminal alternative papers like the Santa Cruz Sun, Kadetsky fell in love with yoga during her time here. There was the rush of excitement when she took her first yoga class as a student at UCSC. The deepening infatuation as she studied Iyengar yoga in Los Angeles. The depth of her devotion as she traveled to India to study with the legendary master B.K.S. Iyengar, and the surprising and sometimes troubling things she discovered there. It's all documented in First There Is a Mountain (Little, Brown; 288 pages, $23.95 cloth), which Kadetsky is returning to Santa Cruz to promote with an appearance Wednesday, Jan. 21, at 7:30pm at Bookshop Santa Cruz. Metro Santa Cruz's highly literate but slightly yoga-challenged reporter caught up with the author on the East Coast by phone. Metro Santa Cruz: Does yoga still play a huge part in your life? Elizabeth Kadetsky: Definitely. I don't practice Iyengar anymore. I practice Ashtanga. That's the jumping-around one, right? Yeah, exactly. But yeah, I have a studio I go to, and a teacher I work with every day. It's not the center of my life in the sense that I'm not a yoga teacher, and what I do when I leave the studio generally doesn't have anything to do with yoga. But the fact that I'm there every day causes it to be a big part of my life, whether I want it to be or not. In your book, you said that relatively few Indian people were interested in yoga--that the feeling was since it was so popular in the West, it would gain popularity in India, instead of the other way around. Is this still something you think is true, or have attitudes changed? My boyfriend and I last year had a roommate who was Indian. He was a graduate student in physics at Columbia. One time I invited him to come to a reading that I was doing at a yoga studio. He was the only Indian in the audience. They had all these statues and pictures of Ganesh and stuff on the walls, and all the Hindu gods, and all this sort of Hindu kitsch stuff. He walked into the studio and he was just floored. He thought it was so funny and so strange. He knew about yoga, but he had never studied it himself. He was always asking me, "Should I take this class at the gym? What do you recommend, what would be the best style of yoga for me to study?" He was interested in yoga because he found out about it in the United States, but he also did sort of idealize it as an Indian tradition. I think Indians feel that yoga philosophy is part of their tradition, which it is, and it's confusing that the physical craft almost belongs to the West. Is the yoga you see in gyms in America very different from the yoga in India? One of my complaints about the way yoga is taught in America is that it's taught in classes--but that was started in India. It was actually started by Iyengar's teacher, Krishnamacharya. Iyengar very much supports the teaching of yoga in classes. It's funny, because in spite of himself Iyengar does most of his teaching individually. He encourages his students to come to the studio in the morning. If you're a serious student, it's expected that you be there and you just practice anything you want for two hours and then you take a class later in the afternoon. But in a lot of ways it's that practice that's the most important part of studying with Iyengar. He's among the people who pioneered classes, and if you asked him he'd say, "Yes, classes. It's the great innovation of modern yoga, because it brings it to more people and it makes it popular," even though I think the reality is he understands the importance of having a more one-on-one relationship with your teacher. It's so rare in the United States, and one of the reasons I study Ashtanga is because you can do what they call the Mysore Practice, which is named after the place in India where Ashtanga is taught. You go at a set time and you do your own practice, and the teacher's there and the teacher works with you individually, but then there are a whole bunch of people there at the same time. But it's not a class in the same sense. It's very different, and I think it's much truer as far as what I'm looking for. What you find in those practices is much more valuable because you have to rely on yourself much more and let your body tell you if you're doing it right or wrong, and anytime you feel confused you can just raise your hand and say, "Teacher, teacher, tell me what I should be doing." Your practice starts with yourself, not your teacher. Is that also true of the philosophical aspects of yoga? I notice a lot of your book dealt with how spiritually it affected people. Well, I think if you're practicing by yourself in a quiet way, you have better access to the ways that the yoga can help you look inside, and just become more sensitive to what you're feeling and how your mind is working and what unknowable things that you're trying to fathom or might have the opportunity to fathom in some way. It's useful for the teacher to yell at you sometimes and guide you, but if that's your only experience in doing it I don't think you have the quiet or the concentration to take it to that next step. I did notice there's a lot of yelling in the story, which seemed different from what I would picture a yoga studio being. I know! The great quote that I love from Geeta [Iyengar's daughter, an instructor at his institute] is her saying, "All this yelling! You are making me un-yogic." I know you were studying to be a yoga teacher; did you ever end up doing that? I decided not to do it. I was teaching. I did the training program in L.A. And I started teaching then, in I think 1995 or so, and I taught all the way up until when I left for India the final time in 1999, so it's been since I've been back from India that I decided I don't want to be a yoga teacher. Or that I don't want to teach yoga classes, actually. I could always teach individuals, but it's not really my profession. My profession is to be a writer, and that's my first love. I don't like teaching yoga the same way I like teaching writing, because writing is about words and yoga is about your body. I find it really hard to talk about yoga, and I find that as a yoga teacher you are always being asked to explain how things work and explain how to do them correctly, and I never feel like I have the right answer. Are you still in contact with Iyengar? Barely, but yeah, I am. I communicate with him through the institute; there's someone I can email there who gets messages to him. I don't study with him, technically, since I haven't been back there. I had to contact him several times when I was working on the book for permissions, and then after I got the permissions from him I got permissions from other people too, and then I thought that he would want to know about the correspondence I'd had with these people because it was sort of engaging and amusing, so I sent word of that to him. He wrote a little note, kind of technical, about when he studied with the maharaja. So nothing extensive. I guess when I came back from India I still felt very close to him and very loyal to him, but, partly to write the book, I needed to get some distance from the Iyengar community. That's when I stopped studying Iyengar yoga and stopped teaching it. I didn't communicate with the institute in India, either. It was too hard to still be part of that world, and be writing about it.

An excerpt from Elizabeth Kadetsky's yoga memoir, 'First There Is a Mountain' I made the decision to go to India to see Iyengar during the L.A. Fires. This was the year that finally put lie to the maxim that California had no seasons. By then, I had been living in California on and off for ten years, long enough to internalize the rhythms to the region's shifts. Drought led to earthquake led to fires led to floods. Our proximity to Latin America also gave us the season of war. And so I traveled to Mexico as a freelance journalist covering the insurrection in Chiapas. In one afternoon, I moved from the site of carnage at an abandoned Mexican jailhouse to news on the TelePrompTers at our Mexican hotel that a massive earthquake had shaken my then home of L.A. I flew back to L.A., where over the next week, the temperature rose something like a dozen degrees a day. Then the Santa Ana winds came, ionizing the air with small particles that made everyone alternately depressed, energized, and ultimately just restless. This only heightened the effect of the pollution from the freeways, which seemed to me to further stimulate everyone's anxiety. I was driving on the freeway one afternoon, trying to determine whether the panicky feeling in my chest was caused by pollution or something more idiosyncratic and psychological, when the pointillist bits that more generally made the air a flat shade of gray slowly began to grow more visible. They were expanding until the air was not gray so much as a speckled canvas of black flakes against white. Over the course of that afternoon, those small flakes swelled. By the time I got home, my front steps were covered in a carpet of soft charcoal, and the sky was raining large flat disks that landed on your head and arms and left impressions reminiscent of the nuclear suntans burnished on victims of Hiroshima. Off to the west was an ominous red glow. L.A. burned like that for four days. Inside, I too was burning. There was something in my chest, what felt like grief and pain at the same time. I was unsettled deep inside, in my veins, in my limbs, in the fibers lacing around my ribs and connecting to my lungs. Contrary to the idea that yoga's popularity in L.A. owed to the deeply bred and rampant vanity, I believed that yoga was suited to L.A. because it was a system of purification and relaxation that worked on two fronts to undo the nefarious effects of smog. A buildup of toxins, my teachers at the Iyengar Yoga Institute of L.A. suggested, could be combated with ten- or fifteen-minute interludes in headstands and shoulder stands. These served to spur the circulation of lymph through your nodes, creating a cleansing effect while also easing whatever urban tension might have built up since the last time you did the poses. This explanation was so relevant to my experience of the city that the teachers at the yoga institute seemed like prophets to me, and I began spending as much of my free time as possible taking in their wisdom. I eventually signed up with Gloria and a handful of others to undergo training to become a teacher. Gloria suggested I write to Iyengar in India to learn yoga from its source, and I did. That afternoon when I tiptoed up my steps, leaving footprints in the carpet of ash, I received my response. It was an invitation to come to India for two months, in the form of an aerogram from the small Indian city of Pune, a sliver of blue parchment with an arabesquelike signature in the script of an institute secretary named Pandurang Rao. The crudely printed Indian postage stamps had the hallowed look of ancient seals. Their script, in Roman and Devanagari letters, evoked something sacred and wise. The aerogram had a literal message as well. Demand to visit the Iyengar institute in India was high these days, and I'd have to wait several years before they could make a place for me. I waited. During those years, I enrolled in graduate school while continuing to practice and teach Iyengar yoga. On a trip home to New York, I called the New York City Iyengar institute to inquire about classes. "Today?" the person on the line asked. "Yes." She paused. Her pause suggested she was guarding some secret society, its exact nature unclear to me an into whose ranks I was for some reason unwelcome. "There's a Level Two class at 10am, a Level Three class at noon, and at three, Guruji's coming to dedicate the studio." "Who?" "Guruji," she said carefully. There was more silence. "Mr. Iyengar?" She paused before uttering yes. "This is the Mr. Iyengar? Not his cousin or somebody? From India? Pune, India?" "Guruji," she said weightily. The environmental contamination I'd escaped in L.A. had followed me to New York on this trip. It was the most foul day of the year--mid-August, about a hundred degrees and sticky. The soot from taxicabs and subways stuck to your skin like sugar. The air felt soggy, like walking through a sponge. New York was irritable, only furthering my theory that bad air worked on the psyche in a physical way. It was a dubious activity to even venture outdoors. I nevertheless made my way to the studio, an unmarked eighth-floor loft on a Midtown side street. Several dozen Americans, many in Indian dress, sat on the wood floor waiting quietly. I sat with them until finally a flash of white appeared at the doorway. I recognized Iyengar from pictures I had seen of his yoga demonstrations, in which he twisted into contortions while wearing shiny shorts. This Iyengar looked smaller inside his loose-fitting garb. Even as he strode through the parting sea of devotees, I was struck by how hefty his belly seemed in the photos and yet how weightlessly he seemed to move. He installed himself at the top of a tall dias sitting cross-legged. His hand gestures were jumpy, his fingers flying to his head again and again to tame his silver mane. His eyes flashed from face to face. One time, they met mine. They made me feel warm, as if there were a furnace inside of me. But then his eyes darted to the next face, kinetically, feeding off the nervousness on the street outside. There, high-pitched melodies cycled on broken car alarms, taxi drivers leaned on horns, pedestrians took out frustrations in shouting matches. The guru seemed as sensitive to the urban irritants as I was. "People say the cities in my country are the most polluted cities in the world," he complained in his difficult accent. "But New York City is worse even than Calcutta." A yogi must perform breathing exercises first thing in the morning, I had read in one of his instruction books. At first I'd taken this as holy if mysterious counsel that had to do with the auspicious quality of the sunrise hours. But as I read on, I learned that in such highly polluted cities as Calcutta, it was only during the early morning that you could breathe a suitable level of oxygen with your air. I had always understood this kind of concern for the sanctity of the human body as related to the fact that yogis tended to be vegetarians. So after Iyengar performed his short speech and a dedication in Sanskrit, I was not at all surprised to find that the celebration meal, specially prepared with Iyengar's favorite foods, was vegetarian. I had become a vegetarian mostly because I never liked the way meat made me feel. It was heavy and goopy, and even as a child I imagined its oils congealing beneath my skin to create a thick layer of noxious gelatin. Sitting at the dinner table with my mother and sister, I used to make sure the garbage was within easy reach so I could deposit forkfuls of meat when my mother wasn't looking. My hunger strikes persisted through the years with my stepfather, when I refused to eat steak or meat loaf or hamburgers. Back then, I spent several evenings sitting alone at the dinner table into the late night in defiance of my stepfather's order that I remain at the table until I was done. By the time I was fourteen, my stepfather long gone, my mother herself gave in. At my urging, we made a vegetarian pact, much to the disgruntlement of my sister. "What does your mother think of this?" my father asked suspiciously from Boston, only to receive the worst possible report. Today, the substance of the Indian buffet confused me. My desire to create a clear and uncluttered feeling in my body had led me to cut other things from my diet that, like meat, seemed to thicken my insides, to muddle my clarity. This was what yoga worked against. But the buffet today was laden with sweet, gelatinous, fatty things: dairy, sugar, refined carbohydrates. Rice pudding. Curries with globules of oil floating on top. I watched Iyengar eat heartily. I imagined the food sinking into his big belly. I saw it undulating on its way there, sprouting bacteria as it swam. Clearly, if there was some equation that connected vegetarianism, purity, and yoga, it had little to do with my own ideas about nutrition. Most of us already knew about and largely subscribed to Hinduism's vegetarian ethics, but we now discovered its particularities. Meat, my teacher explained, was not unhealthy in the literal sense. It defiled you spiritually, tainting you with the act of violence implicit in the journey from life to dinner. Ahimsa, or nonviolence, proscribed against all killing, including for food. The strength of this belief was illustrated by an anecdote Gandhi recounted in his autobiography. His wife, Kasturbai, was perched on the brink of death, delirious. When her doctor recommended a cure of beef bouillon, her life was in her husband's hands. Gandhi resolved that she would rather die than dirty her insides with the stuff of killing. I was excited to travel to a place where I wouldn't have to explain my preference against meat. When I got home that night, though, I was troubled. I couldn't understand why yogis didn't see meat the way I did: it kept you from flying; it weighed you down when you tried to jump to a handstand. I checked my copy of Iyengar's famous manual, Light on Yoga, and there found that the guru, like me, seemed to have a less symbolic idea about eating. His only mention of food concerned its absence. "Asanas should preferably be done on an empty stomach," he wrote. He'd come to this conclusion after having practically starved as a young man in depression-era India, often surviving on just water and tea for days. It was under these circumstances that Iyengar had his first encounter with divinity. "My body was at rest," he wrote of the experience. "My soul was calm. I had no sense of awareness of the things around me. All my thoughts, actions, body and ego were completely forgotten. I was only conscious of that moment of rapture." If meat sullied the body, fasting purified it, he reasoned at this time. Performing asanas was an offering to the Lord, and doing so on an empty stomach cleared the body, leaving space for the divine. It was unclear to me exactly how my predilection toward lightness aligned with Iyengar's idea of the body as an empty vessel, but I felt I was onto something. I too made a connection between fasting--feeling light--and preparing myself for the sweep of epiphany. There seemed to be a link. He called his subject "light" on yoga, after all. [ Santa Cruz Week | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the January 21-28, 2004 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.