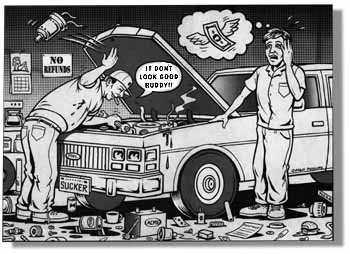

Nervous Brakedown

In the tenuous jungle of auto repair, all it takes is a few bad mechanics to

spoil industry credibility and make consumers cynical

By Michael Mechanic

A MIDDLE-AGED COUPLE DROVE into Jack Sparks' DMV Clinic in

Soquel with an unusual brake problem. It was unusual because the couple had

just spent about $800 on a brake job at a nearby discount shop. The man and

woman, hearing strange noises, had brought their car back to the first shop

several times and were assured nothing was wrong. Sparks noticed from the

past invoices that the first shop had replaced all four brake

calipers--devices that push the brake pads against the rotors--on the

couple's 6-year-old car. "Most calipers should last at least 10 to 15 years,

on average," notes Sparks. "I have never, in more than 20 years in this

complex, replaced all four calipers on any car."

The problem, it turned out, was that the first shop failed to secure pins

that held the calipers in place, and some were falling out. Later, while

talking to a supplier, Sparks made some inquiries and was told the first shop

was ordering about 100 calipers per week. Sparks was dumbfounded. "I replace

20 to 40 in a year, and that's probably an exaggeration," he says.

Hearing the caliper story repeated, Bert Moulton, who runs the Unocal Service

station near Seacliff Beach and estimates that he replaces maybe 50 calipers

per year, had the following response: "Is that right? Wow! Oh, my god, those

poor people!"

Sparks had stumbled across a rather egregious example of what is known in

industry parlance as "overselling"--getting customers to purchase parts and

services that they don't need.

The term is a kindly euphemism for what ranges from overzealous preventative

maintenance to incompetence--and is more often some degree of fraud.

Joe Gomez hears all the stories. He heads the San Jose field office of the

state Bureau of Automotive Repair--or BAR--which oversees the auto-repair

industry and investigates potential wrongdoing. "I don't think you have a

large percentage of bad apples, maybe 10 to 15 percent, but they have large

impact on customer perception," Gomez says. "When somebody upsets you, you

remember it for a long time."

Moulton, normally a mild-mannered chap, says he sees a little red when he

hears about other shops overselling. "I think it ruins our name, it takes

mechanics down as a whole," says Moulton. "Ninety percent of us go the extra

mile for our customers, 10 percent are getting too aggressive, and because of

that 10 percent abuse, people are so down on us that we have to be

extra-careful."

One favorite target of the unscrupulous mechanic appears to be brake systems.

Every mechanic has a brake story to tell. Darrel Robert, one of Moulton's

techs, tells of a car that a customer had towed to their shop several years

ago from a national auto-repair company with local franchises. Robert says

the customer called in tears. "They were telling her she shouldn't drive her

car, that it was unsafe," he says. "I put it up on the rack and everything

was fine. We just put new brake pads on, and we sent her out of here for

about $70. They were quoting her something like $400 to $600."

Gerry Brown, who runs a small garage near downtown Santa Cruz, has similar

tales. "A client of mine went in for a cheap oil change and came back with an

estimate for a $700 brake job," he says. "She called me in a rage, because

we'd recently done a brake job and she thought we'd screwed her. So she

brought it in, and we put her car up on the rack and showed her she didn't

need any of the work they'd recommended. Not one thing."

Brown concurs that these incidents make all the shops look bad. "I think

mechanics are hated, like lawyers and dentists," he says. "I believe

[overselling] happens in every shop that advertises $49 tune-ups and brake

jobs. You can't get anything for $50 in the car-repair business."

Gomez agrees that customers should be alert when doing business with shops

that advertise cheap tune-ups and oil changes. "There is a potential for

misleading when dealing with high-discount situations," he says.

The BAR Code

IF ANY MECHANIC knowingly lies to a customer to sell

unnecessary parts, that is fraud and is illegal. But the line between

overselling and preventive maintenance can be a fine one, difficult for a

customer to distinguish. Mechanics often use the analogy that auto diagnosis,

like medical diagnosis, is a matter of opinion, which makes it very difficult

for licensing agencies to prove wrongdoing.

"At what point is a part no good?" Sparks asks rhetorically. "It's up to the

technician. He might say that the caliper was dirty, or it wasn't fitting in

right."

Gomez says the BAR will investigate such cases if complaints against a shop

appear to follow a pattern that indicates fraud. Investigators may drive to

the suspect shop in undercover cars, the condition of which have been

carefully documented. "When a shop tells us we need to replace [new] parts,

we know they are not telling the truth," says Gomez. "A lot of times the

customer can't account for the condition of parts before going to a shop.

It's very important for us to know the condition of the car."

Offending shops can be sanctioned by the BAR, which may include revoking the

shop's license or placing a shop on probation, requiring office meetings with

BAR officials, surprise inspections and reviews of shop records. "If we find

the core of the problem was a defective repair or carelessness, those kind of

things are not legislated," says Gomez. "Our investigations are concentrated

on people being misled through overt statements, more subtle omissions,

confusion, misrepresentation, or false or misleading advertising. Once you

start to mislead your customer, you are walking into the category of fraud in

one form or another."

Other common fraudulent practices investigators come across include duplicate

billing, in which a car owner receives labor charges for two related jobs as

though they had been done separately, when in fact combining the jobs may

have saved hours of labor.

Another particularly dishonest practice is when a shop charges a customer for

parts and purposely fails to install them. Both Sparks and Brown say they

have seen recent evidence of this criminal practice roll into their shops.

Just last week, in fact, a local mechanic called the Consumer Affairs Unit of

the district attorney's office to report that his shop had done just that on

several occasions. Consumer Affairs Coordinator Robin Gysin says she referred

the mechanic to the BAR.

For her part, Gysin believes the written work estimate--a legal contract--is

the most effective means of consumer protection. She points out that the

customer can check off a box on the form, requesting to see the old parts or

get them back. "That way you can verify, presumably, that they were replaced

with new ones and, if you know that kind of stuff, that the parts needed to

be replaced."

Braking a Claim

IN SPECIFIC DISPUTES, BAR officials encourage shop owners to

reach an agreement with the customer. Some customers opt instead to take

their complaint to small claims court, where plaintiffs can seek damages

totaling less than $5,000. A check of small claims records for 44 local auto

repair shops yielded only four shops with five or more claims by individual

plaintiffs since 1990.

Econo Lube N' Tune at 2842 Soquel Ave. had the most, with 12 cases. (In a

spot check of seven of these cases, all were customers claiming repairs were

done improperly or, in one case, that the shop "charged too much" for a smog

check and pressured the customer to make "additional" repairs. Five of the

seven cases examined were decided in favor of the customers. Another case

initially went to the customer and was later reversed, although the reason

was unclear. The remaining case--in which the man said he was pressured to

make repairs--apparently was decided in the shop's favor.)

The other shops included Goodyear (with six small claims cases since 1990,

covering several franchise locations), Midas (two locations) and Santa Cruz

Auto Tech, the latter two with five cases each on the books.

For information about a shop's reputation, consumers can check with the

Better Business Bureau, which keeps files on various businesses. A check of

some four dozen local repair shops, however, revealed that none had any

complaints filed with the BBB within the past three years that had not been

resolved.

Given some lead time, a customer can also check with BAR to see whether the

bureau has received complaints about particular shops. The request must be

made in writing, however, and it takes about two weeks to get the results,

which may be limiting for commuters.

In an effort to streamline operations, the BAR recently closed field offices

in Monterey and San Francisco, consolidating them into a single office in San

Jose. The office has between 20 and 30 investigators to cover the coastal

region from San Francisco to San Luis Obispo, home to an estimated 5,000 to

6,000 auto-repair shops.

Given the BAR's large territory, the agency's effectiveness is a matter of

some local debate in the industry.

Customers would be wise to educate themselves, say those mechanics

interviewed. Among the most important ways to avoid getting ripped off, they

say, is not to sign anything and instead get a second opinion when a shop you

don't know or trust recommends a major repair job.

When you call around, they say, don't just ask about price, ask about

quality. Discount places in particular may have financial incentives to find

things wrong with your car. Also, ask whether mechanics are certified with

the National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence--or ASE.

While many competent mechanics are not ASE-certified, training and

certification is always a positive sign. "We have the potential of working on

22,000 different vehicles, different [models], foreign and domestic from 1970

on," notes Sparks. "[Overselling] is not always blatant ripping off.

Sometimes it's just incompetence and lack of knowledge.

"You have to send your men for training constantly," Sparks adds.

This page was

designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Jimbo Phillips

From the January 16-22, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[MetroActive

News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)