![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

A Wild Ride at Elkhorn

Dock of the Bay: Kayak Creations ships docked off Highway 1 call out to adventurous explorers interested in kayaking Elkhorn Slough.

Kayaking the twisting channel of the nearby slough offers a world apart

By Amy Kristin Adams

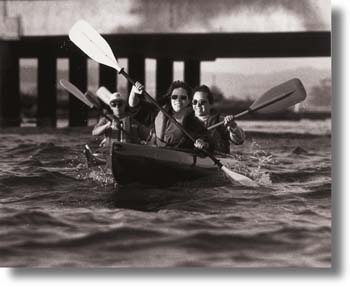

AS MY KAYAK PARTNER AND I SET OFF into Elkhorn Slough, the tall be-hatted fellow who had loaded us into our rented kayak and sent us on our merry way stood waving from the dock. "Don't capsize at the pilings under the bridge," was his parting advice as we paddled around the dock, under the bridge and into the mouth of the slough.

I finally had given in to my curiosity about the kayaks hanging along Highway 1 just north of the PG&E plant. These tantalizing boats advertised sea kayaking, white water kayaking, nature tours and other untold aquatic delights--all offered by the rental company Kayak Connection.

As it happens, the experts who work there do all this and more. You can rent a variety of paddleable objects, from kayaks and canoes to open deck plastic boats. They lead nature tours, sunset tours, moonlight tours and other excursions for the novice or advanced paddler. And those hoping to make the transition from one to the other are also in luck, since they offer classes on all aspects of kayaking.

While all this was news to me, the person behind the counter said people are eager to see the slough year-round. Through rain and fog and sweltering heat, she told me, the slough is a place to behold.

On my first visit to Elkhorn Slough, I had but a vague idea of what a slough might be. I held an image in my mind of something between a bayou and a swamp, and I wasn't far off. A slough seems to go by many definitions, but what they have in common is a river-like channel of water with no river. They are lined with marshy banksand can be associated with the ocean, as with Elkhorn Slough, but do not have to be.

A "tidal embayment" is how Larry Etow, leader of an Elkhorn Slough Foundation nature walk, described it. At high tide, curlicue channels meander off into the mudflats, petering out into marshy muck. At low tide, just the main channel remains, bordered on either side by muddy banks. At either time, a kayak can navigate the slough for most of its seven-mile stretch. The trip takes you through marsh and mud and rolling dunes of sand, eventually tapering off into a swampy ooze.

Successfully navigating the pilings under Highway 1 brings you into the mouth of the slough. It feels much like being at the mouth of a river--which is to be expected. Elkhorn Slough was formed as long as a million years ago as the seaward end of an ancient river. More recently, the Salinas and Pajaro rivers have fed into it, but both of these have since meandered elsewhere. Now Elkhorn remains as a fossil remnant of geological indecision.

While Carneros Creek still empties into the slough during winter months, most of the year Elkhorn is no more than a seven-mile fissure out of Monterey Bay. From above, the bay looks like the site of a giant tug-of-war contest. With one team at Monterey and the other at Santa Cruz, the bay has cracked down the middle near Moss Landing. A submarine canyon running out to sea comprises the underwater end of this rupture, while Elkhorn Slough lies on the inland end.

Wildlife Haven

ELKHORN SLOUGH is largely ignored by the locals, but is a haven for wildlife of all sorts. It held the record for the largest number of bird species sighted in a single day from 1982 until just a few years ago. Over 250 species of birds either live here year-round, or stop by on their spring and fall migratory travels. They are lured here by fish in the water, invertebrates buried in the mud and a restful place to gather strength for the flight ahead.

Otters come to play, eat and rest in the slough's mouth. As my kayak partner and I entered the slough, our first otter-spotting was a writhing mass of fur, feet and splashing water. When we cruised by, two startled otters poked their weasel-like heads out of the water, huffed at us a few times in irritation, then disappeared with a flick of their pointed tails.

People often mistake playing for mating in otters. Actually, mating is a less joyful affair. A male otter holds on to the female's nose with his teeth to hold her in place, leaving older females with scarred, battered noses as a result.

Many otters come to Elkhorn to feed on buried clams. Out in the bay, otters dine on urchins, abalone and mussels stuck to rocks. In the slough, however, they have to dig for their dinner. To crack open a tough clam shell, otters hold a clam against their chest, then whack it open with a rock.

Gulls, excellent scavengers that they are, have caught on to this trick. They recognize an otter with a rock could mean a free meal. One gull I spotted flew over to a feeding otter and landed on its stomach--the bird equivalent of climbing on the table to beg. The otter vanished underwater, then reappeared a few seconds later to eat in peace near the opposite bank.

Like many humans, otters would rather hang out than do just about anything else. And otters are uniquely designed to hang out. Their natural buoyancy provides them with the perfect floating hammock. Their heads rest on the water at an angle to casually survey their world. Two feet away, their back feet poke out straight toward the sky with their tail flopped in between.

Official Seals: A wary group of seals, less outgoing than the playful otters, keep a distance as they watch the approaching kayakers.

No Seals of Approval

WHILE OTTERS are wholly unconcerned with passing kayaks--occasionally swimming closer to get a better look--seals are a bit more wary. There are two seal haul-outs in the first third of the slough, where the mammals relax during low tide. Although you may see the rare seal head pop out of the water, most seals avoid boats and become agitated if you go too near. Staying to the channel's center, you can see beachfuls of seals with their young.

The first of these beaches lies just in front of a favorite pelican hang-out. Brown pelicans--along with terns, egrets, gulls and blue herons--are year-round Elkhorn residents. Although some pelicans migrate to mate in Baja, juveniles remain behind all year. Brown pelicans are the most graceful gliders on the slough, but the clumsiest fishers around.

Singly, or in groups of up to seven, brown pelicans swoop low over the slough, skimming inches above the flat surface. Occasionally, they get so close, their wing tips toss up tiny drops of water. From a kayak, you can see the pelicans' soft lower beak waft up and down in time with their beating wings as they fly low overhead.

When they spot a fish from above, pelicans pause mid-flap, then plummet into the water in a beak-first cannonball dive. Crash-landing in a flurry of feathers, feet and beak, the birds rest motionless for a few moments, then gulp down their feast.

While terns are less flashy (or splashy) than pelicans, they, too, are excellent fishers. Until I purchased my waterproof bird guide, terns and gulls seemed one and the same. But the two can be readily distinguished--terns, from a distance, look like small gulls with very red beaks. After terns catch a fish, they often can be seen flying overhead waving their prizes in the air.

"Sometimes they like to show off," says Caroline Rodgers, staff member of the Elkhorn Slough Foundation.

Pelicans, terns, egrets and many other birds feed on the swarms of tiny fish such as anchovies and top smelt living in the slough. Also drawn in by this mobile feast are lingcod, flatfish and other predators from the bay. But more often than not, larger fish and sharks visit the slough to dine on mud inhabitants.

Mud Wrestling: Rosa Palmer leads her paddling partner, Christine Reyes, through the murky waters near the mouth of the swampy slough.

Getting Down and Dirty

THE MUD of Elkhorn Slough is packed with tiny rubber band worms and fat innkeeper worms, clams, shrimp and even a few fish and crabs taking advantage of ready-made tunnels. Snails and sea slugs glide across the surface eating algae, and the banks at low tide come alive with mud crabs. For thousands of years, silt and debris have drifted along and settled in the slough, now reaching as deep as 20 feet. This creates a sticky menace to wayward paddlers, but is a great place to live for some and to feed for others.

Bat rays dig up clams and worms, crushing the prey between flattened teeth. Leopard and smoothhound sharks, too, feed on buried animals. Scuttling mud crabs make up 90 percent of a leopard shark's diet. While these four to six foot sharks may be deadly to tiny invertebrates, their small teeth and shy nature make them harmless to humans.

Many mud-feeding animals lead lives regulated by tides. At high tide, snails and sea slugs glide across the muddy surface, feeding on algae. Moon snails also go in search of food--in their case, clams. Wrapping their large foot around a clam shell, they drill a tiny hole into its tasty interior. The clam's remains can often be seen washed up on beaches with a single perfect hole indicating its fate.

Another predator on the hunt at high tide is the carnivorous sea slug navanax. This brownish slug with brilliant blue, yellow and white-striped markings follows the slime trail left by other sea snails or slugs. Inching along barely faster than its prey, navanax eventually closes in for the kill, swallowing its victims whole.

At low tide, the mud looks barren, but 3-foot-high spurts of water erupting from the mud suggests life within. These jets come from large gaper clams squirting water out their siphon. These water fountains and the flocks of birds in search of food are the only indication of life below. From a kayak, you can see dowitchers, stilts and willets--all using their long beaks to probe for food. The sensitive tips feel for clams, bugs, or small crustaceans to tweeze out of the mud.

These birds along the bank and in the air are visible year-round to an Elkhorn kayaker. A hard-core paddler can do the whole slough in a day, but for less intrepid souls, the first mile offers wildlife in abundance. For a trip on the slough, it doesn't matter how far you get, just what you see.

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

From the January 2-8, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.